Famed medical researcher helped thousands, and stopped “Typhoid Mary”.

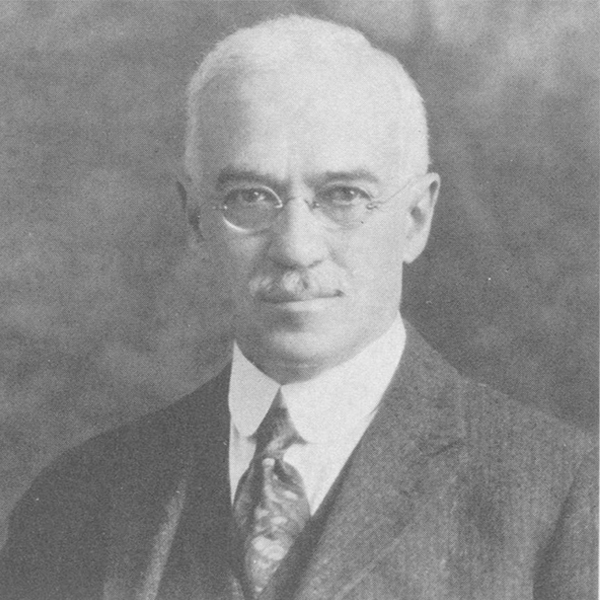

William Hallock Park (1863-1939)

Dr. William Hallock Park, a renowned researcher in the fledgling field of bacteriology in the 1890s and early 1900s, will forever be associated with the conquest of deadly diseases, including diphtheria and cholera infantum—and for confirming the source of a puzzling typhoid outbreak in New York: “Typhoid Mary.”

William was born on December 30, 1863, in New York City to Rufus and Harriet Hallock Park. His father was a wholesale grocer.

In 1883, William graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from City College, then entered Columbia University to study medicine. He planned to become an ear, nose, and throat specialist.

After graduating in 1886 from Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, he traveled to Vienna to learn more about the new science of bacteriology. When he returned, he teamed up with his former pathology professor, T. Mitchel Prudden, to research diphtheria, a deadly childhood disease caused by a toxin that makes it difficult to breathe and swallow, and attacks the heart, kidneys, and nerves. Prudden contributed the lab and expenses; William the time and labor “during late afternoon free time following outpatient clinics.”

In 1893, William was offered a full-time research position with the New York City Department of Health. He and his assistant, Dr. Anna Williams, set up shop in two rooms in a tenement house in the Bowery. A year later, the health department’s chief inspector returned from Europe with exciting news about the discovery of a diphtheria antitoxin and asked William and his team to begin at once to manufacture it.

Within a few months, The New York Herald raised $8,000 to buy 60 horses needed to start producing the antitoxin, and the immunization effort began. When systematically injected with diphtheria toxin, the horses’ immune systems were prompted to develop neutralizing antibodies against the germ’s poison. Initially joined by a few sheep, goats and dogs, horses were used because they were larger and better antitoxin factories.

During the first year, 25,000 vaccinations were given, and they “succeeded magnificently,” Park noted. Between 1895 and 1936, the death rate from diphtheria dropped from 150 per 100,000 to less than one in 150,000.

Success and recognition came rapidly, and William was offered the position of director of New York City’s new Bacteriological Diagnostic Laboratory, the first public health lab in the world. New York’s large, crowded “melting pot,” with its high incidence of infections, provided ample opportunities to diagnose diseases and come up with treatments.

At the turn of the 20th century, cholera infantum, or gastroenteritis, was another top killer of young children. William theorized that poor sanitation often caused bacterial contamination of milk and water supplies. His push for refrigeration and pasteurization led New York to become the first city to regulate the cleanliness of milk being sold. He also lobbied to improve treatment of the city’s water supply. Those successes saved thousands of lives and earned him the nickname “the American Pasteur.”

In the summer of 1906, a mysterious outbreak of typhoid fever erupted in Oyster Bay on Long Island. Six of the 11 people in one house were stricken. A health investigator, Dr. George Soper, who had been hired by the wealthy banker who had rented the home, soon realized that the cook, Mary Malone, had also worked for eight other families who’d come down with typhoid. Twenty-two people had been infected and three had died.

The next year, about 3,000 New Yorkers were infected with Salmonella typhi, and Soper, who had been stalking Mary Malone, soon realized this “heathy carrier” was still spreading disease and death as she cooked in kitchens around the city. The first time the inspector tracked her down, Mary chased him off with a cooking fork. But the second time, he had Mary arrested and taken to an isolation ward, where the city’s bacteria and disease specialist, William Hallock Park, tested her feces three times a week and discovered the bacteria that causes typhoid in nearly every sample.

For two years, Mary was quarantined in a small cottage on North Brother Island, a speck of land in the East River near Rikers Island. Frustrated by the isolation, she sued the health department, claiming she’d been imprisoned without due process. William, the bacteriologist, took the stand to explain how Mary was an “asymptomatic carrier” and would continue to infect people if she were released. The court dismissed her case and sent her back to isolation, but a sympathetic new health commissioner set Mary free.

(APHA Archives Photo)

For the next five years, “Typhoid Mary,” as she was dubbed in book titles and newspaper headlines, flitted from kitchen to kitchen, cooking in local restaurants, hotels and inns using various pseudonyms. After infecting at least 25 doctors, nurses, and staff at a maternity hospital in Manhattan in 1915, she was apprehended and sent back to North Brother Island. Two members of the infected hospital staff died.

Despite the risks of releasing her, William agonized over her isolation. “Has the city a right to deprive her of her liberty for perhaps her whole life?” he wondered. Ultimately, she became a special city employee, working in “voluntary detention” as a paid lab technician in a hospital on the island until her death in 1938, at age 69.

In his 42 years as director of the municipal labs, William and his team of researchers were recognized for their fight against smallpox, rabies, typhoid fever, pneumonia, meningitis, polio (known as “infantile paralysis”), and influenza. But not every battle was won.

In the fall of 1918, soldiers, who gathered in camps around New York before being deployed to Europe in World War I, began dying of influenza, dubbed the “Spanish flu.” William and his colleagues worked around the clock, desperately seeking the bacteria that was causing this epidemic, and trying to find a cure. It was another decade before scientists proved it was caused by a virus. Meanwhile, more than 30,000 New Yorkers, mostly under age 30, died in the pandemic.

(Photo courtesy of the author)

William received countless awards and accolades during his distinguished career. Among them: The Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences and the Sedgwick Medal from the American Public Health Association, both in 1932; the Townsend Harris Medal from the College of New York and the Distinguished Service Medal from the Theodore Roosevelt Association in 1935; and the George M. Kober Medal from the Association of American Physicians in 1937.

He was president of the Society of American Bacteriologists in 1912, of the Society for Experimental Pathology in 1920, and of the American Public Health Association in 1923.

In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a letter to be read at the dedication of a new laboratory building bearing William’s name. “Your contributions to medical progress will continue to benefit the people of New York, and of the Nation, and of the World long after this splendid laboratory has crumbled into dust,” Roosevelt wrote.

William Hallock Park never married, and although he officially retired from the city health department in 1936, he continued to work in his laboratory until the day he died of a heart attack, April 6, 1939. He was 76.

The William Hallock Park Reserve Fund in the New York Community Trust is used for medical research grants, particularly research in bacteriology and virology.