Industrialist created company that forged specialty steel products. Left his estate to The Trust.

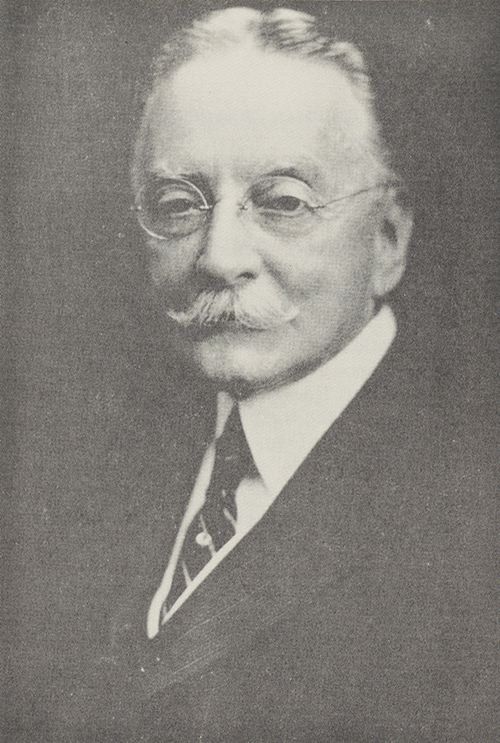

Wheaton Bradish Kunhardt (1859-1933)

When Adm. Richard Byrd and Floyd Bennett first proved that man could circle the North Pole by airplane, their sensational 1926 success was vicariously enjoyed by a gentleman they had never met, yet he played a small but essential role in their feat. He was Wheaton Kunhardt, chairman of the company that made the special steel for their engine. A year later, Wheaton had the satisfaction of knowing that his steel was helping propel a shy young pilot named Charles Lindbergh across the Atlantic.

It is not surprising that Wheaton’s company—Carpenter Steel—had contributed to these historic firsts. In prior years, Carpenter Steel had developed the world’s first chrome-nickel alloy steel and had adapted this to produce the first armor-piercing projectiles in the United States—projectiles that helped Adm. George Dewey rout the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay during the Spanish-American war. Nor was it surprising that Wheaton had become chairman of such a pioneering firm. Not only was he a veteran mining engineer but also an excellent administrator and an enterprising businessman.

Enterprise may have been a family trait. His father, a German, strongly opposed his country’s rising militarism and, in protest, left Hamburg in the 1840s. After working in South America and Hawaii, he heard of the California Gold Rush and cashed in on it by arriving in food-short San Francisco with a cargo of grain that brought very high prices. When the San Francisco fire later wiped out his fortune, he joined a foreign trade company his brother had established in New York City. It was in this city, in New Brighton on Staten Island, that his son Wheaton was born and educated, first at the Charlier Institute and then at Columbia University’s School of Mines.

After graduating as an engineer of mines in 1880—much later, he was given an honorary master’s degree—young Wheaton traveled extensively and studied in Europe and out West. He started his career as an assistant to George W. Maynard, a prominent New York consulting mining engineer. Five years later, he joined the Boston Heating Co. as assistant engineer, and in 1890, began diamond drill exploration of coal deposits in Rhode Island. He then researched direct steel processes and the magnetic separation of iron ores.

He was an extremely bright young man, on alert for good opportunities and almost precociously capable when given them. In 1893, when he was only 34, he was named president of the Osceola Placer Mining Co. of Nevada.

His brilliant mind and business acumen proved so conspicuous that in that same year, the Carpenter Steel Co. in Pennsylvania, then four years old and famous for its armor-piercing steel, asked him to join its board of directors. In retrospect, the company believes his advent was an important milestone in its development. In 1895, he was made second vice president; in 1904, treasurer and general manager; in 1916, president; and in 1920, chairman. When he joined the firm, it was trying to recover from a disastrous fire that had destroyed its steel plant. Wheaton helped it rise from the ashes. By the time he became general manager, most of the company’s pioneering officials were older men, retiring or retired. Wheaton helped rejuvenate the company, bringing in young men of vision and perspective, and reorganizing it for efficient, modern production.

A desire for efficiency seems to have been a personal characteristic. A business associate recalls that “his office was so neat I wondered how anyone so busy could be so tidy.” A short, spare man with wavy gray hair and a flowing moustache, he always was meticulously correct in his dress, with every detail exactly in place. And he was extremely punctual. A niece remembers asking the time of breakfast. “I always dress in 29 minutes,” he answered. And he did. A person so fastidious is sometimes a bore. But not Wheaton. Within his family, his nieces and nephews—he never married—knew him as a warm and sympathetic friend, a generous and beloved uncle who was a popular visitor and guest, a cultivated, interesting man. And in business, he was admired for his active imagination and foresight.

At the time Andrew Carnegie was concentrating on mass production of general, structural steels, Wheaton Kunhardt urged the Carpenter Steel Co. to continue doing the opposite—to concentrate on high-quality, more expensive, specialized steels. He emphasized research, and under his leadership, the company began to make stainless steel. It became the first company to manufacture high-grade steel for the automotive and aircraft industries, and developed the world’s first free-machining stainless steels, providing industry with the finest and easiest-working stainless ever made.

Only a year before the United States entered World War I, Wheaton became president of Carpenter Steel, and, under him, the firm became a major supplier of U.S. ordnance. It also produced one of the first stainless steels used in Liberty airplane engines, which powered military aircraft during the war. Then, its tool steels got to be extremely popular in machine shops. Alloys became a company specialty under Wheaton, and Carpenter Steel patented a process for using selenium and tellurium as alloying elements for high-quality stainless steel.

Having helped Carpenter Steel become one of the country’s leading manufacturers of premium specialty steels, Wheaton broadened his business activities. He was interested in the American Institute of Mining Engineers, and became treasurer of the Parish Manufacturing Co. in Reading, Pennsylvania, where Carpenter Steel has its headquarters. In addition, he was a director of the Farmer’s National Bank in Reading and president of Reading’s Chamber of Commerce. Yet, he lived much of the time in New York, where Carpenter Steel also has offices, and was a member of the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the New York Botanical Society, and a fellow of the American Museum of Natural History. His involvement in the latter revealed a deep and lifelong interest in nature.

Nature study, often pursued during long horseback trips—in his youth, he was an expert horseman—occupied much of his spare time. Although he was a prominent business leader, he was not gregarious. At his leisure, he preferred to be alone with his books, particularly literary essays and books on American history and the natural sciences. He was, in fact, rather reserved, but his few friendships were deep. And in a quiet, discreet way, he was very generous. He died in 1933, in the very depth of the Depression, at age 74, and left his estate to The New York Community Trust for general charitable purposes.