Bavarian immigrant gave NYC the Naumburg Bandshell.

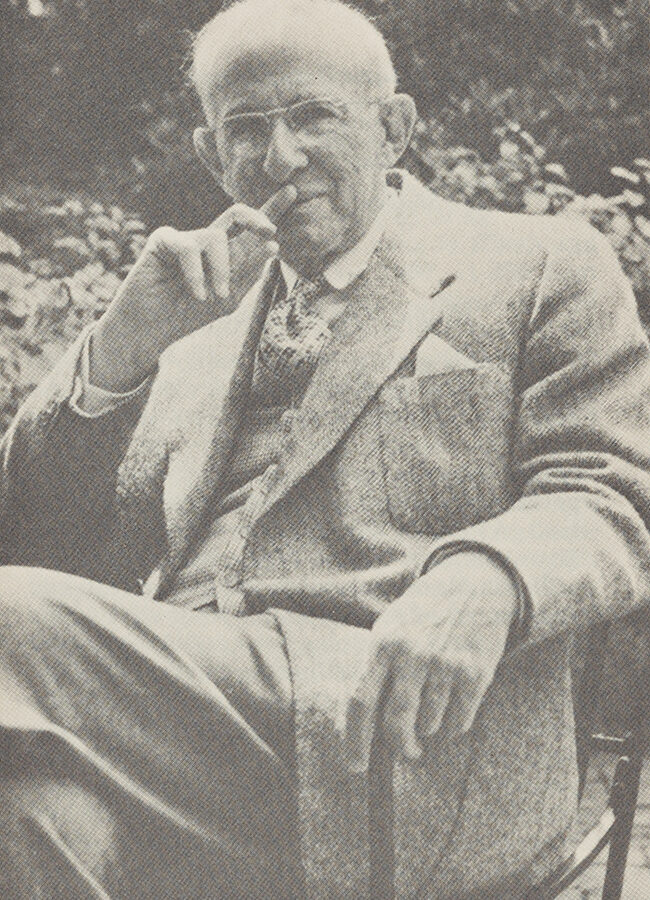

Walter W. Naumburg (1867-1959)

In 1960, Walter W. Naumburg’s will established memorial funds in the New York Community Trust to continue the Naumburg Orchestral Concerts and the Walter W. Naumburg Foundation, both of which had been created during his lifetime.

“Music was his main love”

“Besides giving up the cello, I have had recently to stop swimming in cold water and stop playing golf. It is possible I am getting on.” The speaker, Walter Wehle Naumburg, was 90 years old. He had played the cello for 78 years. At 88, he thought nothing of motoring 3,000 miles all over England. At 90, he flew all over South America.

This agile octogenarian and nonagenarian had spent most of his life and a large part of his private fortune helping young composers and needy musicians, furthering music scholarship, and elevating the musical taste of the public. He and his brother, George W. Naumburg, continued to sponsor for more than 40 years a series of free public concerts in Central Park begun by his father in 1905. He had long since established a foundation that paid for the debuts of promising musicians each year. He was, a cousin recalled, “a bright, intellectual, warm man with many interests and a fondness for young people. But music was his main love.”

Music and long life came naturally to Walter Naumburg. His father, Elkan Naumburg, was born the son of a cantor in Treuchtlingen, Bavaria, in 1835. By the time the prevailing anti-Semitism of his native land drove him to America at age 15, Elkan’s knowledge and love of music were so well grounded that he could play piano by ear. In the New World, he saved his pennies to buy tickets to hear Vieuxtemps and Thalberg, and all his life he expressed disappointment that he had missed hearing Jenny Lind because he could not raise the $7 needed for the ticket.

In America, Elkan Naumburg met Bertha Wehle, daughter of a wool merchant who had emigrated from Prague. Their marriage in 1866 brought together long-lived stock, for both their mothers reached 93 years and Elkan lived to be 89.

Walter Naumburg was born to Elkan and Bertha on Christmas Day, 1867, at 236 E. 23rd St. in New York—the home of Bertha’s father. (Holiday births ran in the family: Walter’s younger brother, George, came along on the Fourth of July, and their father was born on New Year’s Day.)

Father and home were perhaps the two strongest impressions on Walter’s childhood. For 50 years, the Naumburg home was the scene of weekly chamber music sessions. Leopold Damrosch and Theodore Thomas, two great rival conductors of the day, were regulars, as was Marcella Sembrich, the Metropolitan Opera’s leading soprano. Damrosch himself played first violin and conducted the Oratorio Society of New York, which was organized in the Naumburg parlor and given its name by Walter’s mother.

Elkan Naumburg was a rather austere man. His children and nephews found him stern and fear inspiring. Yet, they thought of him with great affection. Walter loved to tell how his father, playing the piano by ear, ran off excerpts from Beethoven’s Archduke Trio in F major. A friend took him to task, pointing out that the Trio was written in B-flat major. “It doesn’t make any difference to me,” said the elder Naumburg. “I play everything in F major.”

Walter started playing the cello at the age of 8. When he was 17, his father brought a cello home from a trip to Dresden. Inside it was the inscription, “Francesco Ruggeri Cremona 1697.” Its last owner, his father had been told, was the last king of Hanover, George V. The cello was Walter’s until the day he died.

Until he was 14, Walter attended Sachs Collegiate Institute in New York. Then he was sent to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to be tutored by Francis Ellingwood Abbot, a retired Unitarian minister who was an authority on English ballads and Chaucer. After three years, Walter entered Harvard, which, he said many years later, “was a cinch after my work with Dr. Abbot. I read Shakespeare with Professor Francis. J. Child and also studied with George Lyman Kittredge, who was young and inexperienced at that time.” By the time he graduated cum laude with the class of 1889, Walter Naumburg and his cello had become regulars in the Harvard Pierian Sodality Orchestra, Shakespeare had become his favorite author, and Harvard had become, after music, his second-greatest love.

In 1890, Walter entered his father’s mercantile business. Three years. later, father and sons created the banking firm of E. Naumburg and Co. to lend money to commercial firms. The name became one of the most admired in banking. “It stood for absolute ability and integrity,” recalls one collateral relative. “The Naumburg name could open any door.” Such admiration brought success: In 1918 alone, the firm sold $325,000,000 worth of commercial paper.

While the family banking business prospered, so did the family love of music and Walter’s participation in it. He enjoyed occupying the family box in Carnegie Hall, which his father had taken continuously since 1890. He played his cello weekly with a professional quartet. He helped organize the Society of Amateur Chamber Music Players. And in 1905, he heartily approved when his father offered to sponsor free public concerts of good music.

From then on, three were held each summer on the Mall in Central Park, where the audience sat in a circle around a small octagonal bandstand and listened to Franz Kaltenborn conduct “Gems from Wagner” or single movements of a classical symphony.

In the 1920s, the People’s Music Foundation Inc. was created to continue the concerts as a Naumburg philanthropy. And the bandshell on the mall was given “to the City of New York and its Music Lovers” by Elkan Naumburg. Designed by Walter’s close friend and cousin, William G. Tachau, the Indiana limestone bandstand offered a 36-foot stage and semicircular dome that embodied (according to its dedication program) “the highest achievement in the science of acoustics.” The claim has been proven by a century of continuous use. At the dedication in 1923, Edwin Franko Goldman conducted his now-famous march, “On the Mall,” dedicated to Elkan Naumburg.

The year 1923 was important in Walter’s life. After 56 years of bachelorhood, he met and married Elsie Binger, a well-known ornithologist and author of a report for the American Museum of Natural History titled The Birds of Mato Grosso, Brazil. He and his bride maintained a home on East 64th Street in New York and a country place in the Silvermine section of New Canaan, Connecticut. There, on 50 acres, they raised dogs, chickens, and prize flowers. (One summer they took 10 firsts, six seconds, and two thirds at the New Canaan Flower Show.) Each Saturday, succulent broilers and colorful bouquets were sent to 64th Street, to be enjoyed by those who came for bridge or chamber music on Sunday.

When Elkan Naumburg died in 1924, his sons, Walter and George, continued the three summer public concerts and added a fourth on July 31, the date of their father’s death. For New York’s music lovers to continue to enjoy the concerts, they knew the programs would have to keep pace with the public’s musical taste and sophistication. A cousin who ran the series for 25 years, Edward S. Naumburg. Jr., pioneered the introduction of opera performances within the outdoor concert series in the 1960s. But when the Metropolitan Opera took its repertoire out into the parks, it was discontinued. In the 21st century, under Christopher W. London’s leadership, the concerts now present at least some contemporary compositions in their programs of entire symphonies and concerti. These concerts often present young musicians and newer ensembles, and, when feasible, performers who have won the W.W. Naumburg prize are featured soloists.

In addition to the concerts, Walter established the Walter W. Naumburg Foundation Inc. in 1926. Ever since, it has conducted annual auditions and given debut recitals in Town Hall to the winners. Beginning in 1949, it also undertook a series of recording awards that brought the works of outstanding American composers to disks. Winners who went on to fame include the Canadian soprano Lois Marshall, pianist William Kapell, and Metropolitan Opera star Laurel Hurley.

In retirement, Walter was even busier than he was in business. He retired when E. Naumburg and Company closed its doors in 1931. For another 22 years, he continued to play the cello at weekly chamber music sessions in his home, particularly enjoying Beethoven’s string quartets and some of Brahms’ later chamber pieces. Not until he was 85 did he give up playing. “The physical exertion was not too bad,” he said then, “but there is a considerable strain upon one’s emotions and concentration. Of course, I could have taken up lighter Mozart and Haydn pieces, but that’s baby stuff.”

Walter traveled frequently to Harvard and to Princeton University as a member of the advisory councils to the music departments at each college. He was president of the Musicians Foundation, which supports musicians in need. He was a director of Mount Sinai Hospital for 41 years, and either a trustee or director of the Northeastern Conservatory of Music, the American Museum of Natural History, the New England Conservatory, the Salvation Army, the National Federation for Junior Museums, and the Greenwich Audubon Nature Center. He also was chairman of the Music Committee of Town Hall.

To fill his spare time, he took courses at the Bread Loaf School of English in Vermont, where he became a close friend of Harry G. Owen, then dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University. He traveled widely—one estimate is that he crossed the Atlantic 45 times—and, on a trip to the Pyrenees with his wife, called on Pablo Casals. “He played the whole of the Bach D-Minor Suite for us,” Walter recalled. “I told him I would never try to play it again after hearing him do it, but he said this just ought to spur me on.”

Elsie Binger Naumburg died in 1953, when Walter was 85. Though he gave up playing the cello that year, he continued his lively interest in music and travel. With Harry Owen, he cruised the Aegean one year and motored through the Canadian Northwest the next, then all over England the year after. When Harvard built its Music Library building, he gave generously to endow its Spalding Room.

His 90th year found Walter Naumburg, in the words of The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town, “a vigorous, clean-shaven philanthropist with a good head of hair, a piercing gaze, a strong voice, high black shoes, a lively and well-stocked mind, and total recall.” Probably one secret of his vigor was his willingness to keep up with the times. Though he found “modern” music difficult to understand, he encouraged his foundations to support contemporary composition. And while he believed no recorded music could compare with a good live performance and never had a record player in his home, he realized how much radio and records had done to educate the public’s musical taste. And if the airplane was the means of seeing South America, he did not hesitate, at age 91, to get aboard and take off. (When two of four engines failed over the jungle of Brazil on the nonstop flight from Buenos Aires to Caracas, an emergency landing at torrid Belem, exactly on the equator, left Walter Naumburg, for perhaps the first time in his life, skeptical about the achievements of the Machine Age.)

In June 1959, Harvard’s class of 1889 celebrated its 70th anniversary. Walter, in a long letter to his 13 surviving classmates, wrote: “I go to a great many concerts, such as the Philharmonics, Boston Symphonies, and the Philadelphias, also the Bach Aria Society, American Opera Society, Hunter College Series, Metropolitan Opera, Kroll Quartet, and I usually take with me widows of my past friends who have gone before them. My brother says that I have a harem.” The letter concluded with plans for still another summer tour, this time to Geneva, Interlaken, and Cherbourg. But the trip was never made. As summer came, the lively old man became, almost before friends and family could realize it, a very old man. On October 17, within reach of his 92nd birthday, Walter Naumburg died.

While he left no descendants, Walter Naumburg did leave the rich heritage in music that had come down to him from his father. Each summer in Central Park, the Naumburg Bandshell on the Mall echoes his devotion to the City of New York and its music lovers.