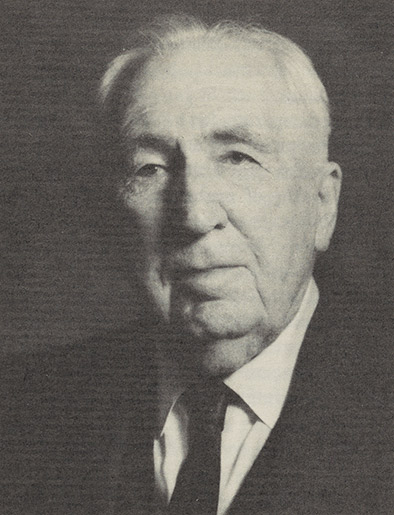

Educator who was devoted to both mathematics and music.

Walter B. Ford (1874-1971)

The year was 1903. Walter Ford sank dejectedly into his chair, head in hands, shoulders dropping. His wife, Edith, knelt by his side, patting his arm, waiting for her husband to tell her what had happened and unwillingly guessing what it might be. Silently, Walter handed her the letter from the faculty of mathematics at Harvard University. Edith scanned the letter and confirmed her fears: Walter’s doctoral thesis had been turned down. The faculty, which included some of the country’s outstanding mathematicians, questioned. the significance of Walter’s work, “On the Problem of Analytic Extension as Applied to Functions Defined by Power Series.” It would not, they regretted to inform him, fulfill the final requirements for his doctorate.

“After all that work,” Edith sighed, close to tears.

Walter nodded, speechless with disappointment. Then he hugged his young wife and reassured her: ”They’re wrong, of course. They’ll retract that statement in the end. You’ll see everything will work out. It just might take longer than we had planned.”

There had, indeed, been a great deal of work. First, the years of study and preparation. Next three years of teaching at the University of Michigan. Then Walter’s decision, made after talking with members of the faculty at Harvard, to go abroad for a year of study, mostly in France and Italy, to familiarize himself with some of the new mathematical ideas that were developing there. Then, when the year was over, his return to a one-year appointment at Williams College. While he was at Williams, he had begun work on his doctoral dissertation, a result of the inspiration he had gained during his European experience. And now the Harvard faculty had dismissed his work as “of little significance.”

It was not Walter Ford’s way to dwell on disappointment. The next day, he mailed his paper to the editors of Journal de Mathematique. The French journal had previously published an article he had written, and during his European trip, he had become acquainted with the editors. The French editors reported so enthusiastically on Walter’s work that the Harvard faculty had second thoughts about the importance of the paper. Though it took two years, they withdrew their criticisms in 1905 and sent Walter a second letter, this time informing him that he was to be awarded his doctorate.

Walter Burton Ford was born in Oneonta, New York, on May 18, 1874, the son of Sylvester and Emogene Burton Ford. Sylvester Ford was a descendant of Martin Ford, the first of the family to leave England for America in 1680. So far as is known, the family was not related to Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Co.

Walter’s father was a prosperous businessman and an astute investor. He and his brothers had invested in a small company in Binghamton, New York, which was a predecessor of IBM Corp., and his early investments in that company created the wealth that enabled his son to become a philanthropist. Walter attended public schools in Oneonta, and then, like other young people in his hometown who wanted to be schoolteachers, he entered the Oneonta State Normal School. The year was 1889, and he was only 15. After his graduation in 1893, he enrolled at Amherst College in Massachusetts. Walter’s interest in mathematics originally had been stimulated by his efforts to understand the motion of the Great Comet of 1882, which had flashed through the skies when Walter was 8. However, after two years at Amherst, he became dissatisfied with his curriculum, and he left Amherst to enroll at Harvard in 1895. He graduated with honors and his bachelor’s degree in 1897 and received his master’s degree in 1898. Now he felt he had been a student long enough, and he was eager to begin teaching others.

There was another reason Walter was eager to start working: He was thinking of marrying. One of his fellow students at Oneonta was Edith W. Banker, the daughter of John D. Banker, farmer, professional auctioneer, and prominent citizen of the village of Ovid. Banker had made a name for himself in Seneca County politics in the 1880s and 1890s. Edith had always wanted to become a schoolteacher, and after her graduation from Ovid Union High School in June 1892, her father encouraged her to enroll at Oneonta State Normal School. There, she met Walter, already a senior when she was in her first year. It was to be an enduring romance. While Edith continued her studies at Oneonta, Walter was studying at Amherst. After her graduation in 1896, Edith went to Radcliffe for additional study, a choice that may have been influenced by the fact that Harvard—and Walter—were close by. When Edith had completed her studies, she got a teaching position in New Britain, Connecticut, and once again the sweethearts had to endure long separations.

When Walter got his master’s degree in 1898, he quickly discovered, to his dismay, that there was little demand for teachers of mathematics. He managed to get a job at the Albany Normal School, (now the State University of New York at Albany) and, the next year, at a private preparatory school, the Albany Academy. He later recalled that he did not particularly enjoy either position, but he stuck them out.

Then, in 1900, “as if from heaven,” he wrote later, he was offered an instructorship at the University of Michigan, which needed mathematicians as a result of an influx of veterans of the Spanish-American War. In his memoirs, Ford noted that his “duties consisted of a heavy load of teaching freshmen only, and in classes so large that students were using radiators as well as chairs and benches for seats. But, at last I was started on my chosen career.”

After a courtship that had endured for eight difficult years, he also was able to get married. His appointment to the Michigan faculty came through early in the fall, and he and Edith set their wedding date immediately. They were married at the Banker farm near Ovid on October 25, 1900. Immediately after the ceremony, they left for Ann Arbor, Michigan, which was to be their home, except for occasional interruptions, for the next 40 years.

The first interruption was in 1903-04, when the Fords were in Europe, and when they returned to this country, Walter began teaching at Williams College in Massachusetts.

But in 1905, Walter returned to the University of Michigan as an instructor. It was that year that his thesis was finally accepted by Harvard, and he became Dr. Walter B. Ford. For the remainder of his distinguished career, Walter stayed at Michigan, advancing steadily up the academic ladder to assistant professor in 1907, junior professor in 1910, associate professor in 1915, and full professor in 1917, a position he held until he retired in 1940.

During the academic year 1928-29, the Carnegie Institute for International Peace sponsored his lectures at universities in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Italy. Ford was among those who worked quietly behind the scenes during the establishment of the Mathematical Association of America, serving as its president in 1927 and as editor of the American Mathematical Monthly from 1922 to 1927. In 1972, the association established the Walter B. Ford Lecture Fund with a grant that derived from his estate.

Walter Ford was a prolific writer. He believed that the time had come for a rebirth of interest in mathematics in America, and he felt this could happen only by instituting major modifications in instructional materials and classroom methods. Consequently, in the late teens and early 1920s, Ford co-authored with Earle R. Hedrick an entire series of textbooks for secondary schools and colleges. The series represented major breaks with previous methods of instruction, and it was widely used.

Walter’s other books included “Studies on Divergent Series and Summability” in 1916; “College Algebra” in 1922; “Analytic Geometry” in 1924; and “Differential and Integral Calculus” in 1928, the last a beginning calculus that was a substantial step away from methods then in use.

At the same time, in addition to his classes and his writing, Walter pursued his own mathematical studies. The results appeared frequently in professional journals.

Meanwhile, his home life was tranquil and rewarding. He and Edith became parents of two sons, Sylvester and Clinton. Each summer they returned with their growing boys to Ovid, in the beautiful Finger Lakes region of New York, to visit Edith’s family. In 1908, they purchased property on the shore of Cayuga Lake. It was not until 1932 that the Fords were ready to build on their land, and they spent the next seven years preparing their retirement home. In 1940, Walter left his four-decade teaching career for a retirement that was nearly as active and continued for 31 years. When Walter B. Ford died on February 24, 1971, only three months short of his 97th birthday, a vast amount of work-in-progress was still spread out on his desk—a splendid indication of the active state of his mind.

During his lifetime, Walter Ford acquired a reputation of civic awareness and philanthropic interests. When Edith died in 1959 at age 85, Walter was for a time, overcome with grief. Then he began to look forward positively. As a lasting tribute to his partner of 59 years, he made a gift of the Edith B. Ford Memorial Library to the people of Ovid.

Music was Walter Ford’s avocation. As ties developed with nearby Ithaca College through his friendship with members of the faculty, he decided to help fill the school’s need for a music building. In 1965, he was present at the dedication of Ford Hall, with facilities for 500 music students. Three years later, he returned to hear the first concert on the magnificent pipe organ he had donated for the 750-seat Walter B. Ford Auditorium.

Walter Ford was a strong believer in making contributions during his lifetime. His gifts benefitted a number of educational institutions, including Harvard University, the University of Michigan, Eisenhower College in Seneca Falls, New York, of which he was a charter trustee, and Wells College in Aurora, New York. And through a fund established in The New York Community Trust by his will, Walter also ensured his philanthropic endeavors would continue even after his long and rewarding life came to an end.