World-renowned doctor creates fund at The Trust to eradicate leprosy.

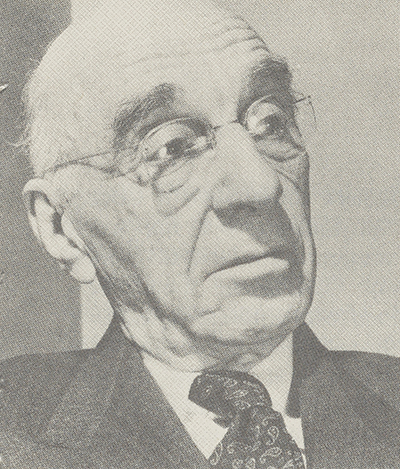

Victor G. Heiser (1873-1972)

The young man stretched out on the polo field had been struck by a ball. Blood spurted from a deep cut in his forehead. Still conscious, he looked up at the tall, slender man who had rushed to his side and implored, “Won’t you look after me, Doctor, and have my surgeon help you?”

The patient was Edward, Prince of Wales. He was visiting the Philippines, and the year was 1922. The doctor, who realized he had a future king in his care, was Victor Heiser, at that time a member of the International Board of the Rockefeller Foundation. The prince recovered and continued his tour; in time, he became King Edward VIII of England and then the Duke of Windsor. The doctor, too, resumed his duties, which ultimately took him to more than 60 countries in the interest of public health.

Victor George Heiser was born on February 5, 1873, the son of a Johnstown, Pennsylvania, merchant. An only child, Victor was very bright, and his parents were determined he should receive the best possible education. During the day, he attended public schools, and in the evenings, he was tutored in French and German. In the summer, he was sent to private classes. As a result of this intensive early education, Victor wrote later, he found himself at the age of 16 “ready for college, but ill-equipped for life.”

However, tragic events dramatically altered Victor’s destiny. The year was 1889, and during the month of May a cold rain had fallen so steadily that the small city of Johnstown was knee-deep in water. During the afternoon of May 31, the water continued to inch higher. Victor’s father was concerned with the safety of his horses, tied in their stalls on somewhat higher ground. He sent Victor to unhitch them. Before the boy could return to the house, a tremendous roar, followed by a series of crashes, signaled the collapse of the dam north of the town. Victor scrambled to the stable roof. Seconds later, he saw his home and his parents swept away. Miraculously, the boy was able to hang on to his precarious perch as it, too, was carried away by the raging torrent. Eventually he reached safety.

Friends offered Victor temporary shelter and food, and he set about redirecting the course of his life. All his family’s assets, except for some real estate, were gone. For a time, he worked as a plumber. Next, he learned carpentry and cabinetmaking. But, once he had acquired skills and proficiency in these trades, he found the challenge was gone.

Using the proceeds of the sale of his family’s property, Victor was able to enter engineering school. Within a year, he decided to become a doctor instead. Mostly through independent study, he acquired credits equivalent to a Bachelor of Arts degree, and three years later, he completed the four-year course at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. It was during his internship at Lankenau Hospital that he made another important decision: “I knew I was not going to be either a general practitioner or a specialist. The prevention of disease on a wholesale basis appealed to me far more.”

Victor Heiser never allowed himself to become discouraged by unfavorable odds. He had, after all, survived a disaster that had taken 3,000 lives in a matter of minutes. So, while vacationing in Washington, D.C., he spied an announcement of the exam for the U.S. Marine Hospital Service and decided to sit for it. Only three of the 42 candidates would be accepted. Although he had had no special preparation for the grueling, two-week exam, Victor again was among the survivors.

One of Victor’s first assignments was with the Immigration Service, which put him in charge of inspecting entire boatloads of new immigrants, many of whom came with debilitating or contagious diseases and had to be turned back.

It was during his tour of duty with the Immigration Service that the young doctor began his international expeditions, in which he functioned not only as a doctor but also as a diplomat. He was sent first to Italy, where his job was to persuade the authorities to help prevent the ailing from attempting to emigrate. His next stop was Egypt, where bubonic plague had broken out and it was feared that contaminated goods were being exported to the United States. Then to Canada, where many immigrants who would have been turned away at regular points of entry were permitted by lax immigration laws to slip into the United States. As a result of Victor’s persuasiveness, the Italians, the Egyptians, and the Canadians all responded to his efforts and cooperated with him and his mission.

In 1903, after five years of experience, Victor was named chief quarantine officer of the Philippines. When he arrived in exotic Manila Bay, he was struck by the beauty of the Islands. But he soon discovered that dreadful health conditions prevailed, and he set a goal of saving 50,000 lives a year by teaching the rules of sanitation.

His biggest task was convincing Filipinos to follow rules that seemed meaningless to them. Although he often lived surrounded by disease—cholera, typhus, smallpox, leprosy—Victor was sick only once. Only once did he break his own rule: He drank unsterilized water and promptly fell ill with amoebic dysentery.

Among the problems he confronted and solved during his stay was the desperate need for nurses. He asked one of the few American nurses to produce a play that would present nursing in a positive light. The play’s presentation was made into a social occasion, with invitations sent to the most influential people. So convincing was it that 15 young women signed up. But they had not been in training long when their parents tried to take them home, claiming their daughters had been “dishonored” by having to care for male patients. Victor, who had quickly learned practical psychology, agreed they should leave at once—in fact, he said, he insisted upon it. His ruse worked. Now the parents wanted their daughters to stay. So, Victor allowed himself to be “convinced” that the girls might stay. When a hundred more than he could accommodate also came for the training program, he had no choice but to turn them away. Victor responded by citing a law that a public officer could be fined and punished for an unauthorized expenditure of funds. The Legislature immediately appropriated enough money for the inclusion of the extra students. Victor’s student nurse recruitment program was a resounding success.

Technical problems had to be solved as well. Two years after his arrival on the islands, the 32-year-old doctor was appointed director of health in the Philippines, a position he held until 1915. Soon after he was appointed, he made vaccinations compulsory in the Philippines. Victor was determined to vaccinate every inhabitant of the archipelago and keep them vaccinated. In addition to carrying out massive education programs to overcome superstition and fear, a way had to be found to keep the vaccine cold to preserve its effectiveness. And since many of the inhabitants lived in remote areas, many days of foot-travel from refrigeration facilities, Victor tried to contrive various cooling devices. None worked efficiently over prolonged periods. He even consulted Thomas Edison, but Edison was unable to offer a solution either. Finally, the Dutch in Java developed a vaccine that could withstand the high temperatures, and over a few years, 12 million vaccinations were given. When Dr. Heiser left the Philippines in 1914, smallpox had been virtually eradicated.

One of the most severe problems was financial. Victor faced the difficult challenge of isolating and caring for thousands of lepers who lived in the Philippines. Some 1,200 new cases developed annually, and nothing was being done for them. Victor established a colony on the isolated island of Culion, but his work there was hampered by lack of money. Leonard Wood, governor general of the Philippines at the time, took particular interest in the fate of the lepers. He was horrified to find that only one out of six patients at Culion was receiving proper treatment. Wood finally agreed to lend his name to a fundraising program. The Leonard Wood Memorial for the Eradication of Leprosy was founded, and $2 million was secured. Half the money was earmarked for the care of lepers, the other half for research.

By 1914, Dr. Heiser believed his work in the Philippines had been accomplished. That summer, he left the islands and joined the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board as director for the East. For the next 20 years, Victor continued his travels, concentrating on Southeast Asia. “My mission,” he wrote, “was to ‘open the golden window of the East’ to the gospel of health, to let in knowledge, so that the teeming millions who had no voice in demanding what we consider inalienable rights should also benefit by the discoveries of science, that in the end they, too, could have health.”

An early assignment with the Rockefeller Foundation was in Ceylon. There, the task was to convince the British tea growers to let him work against hookworm, which was debilitating thousands of workers in the labor force. An adept administrator as well as a humanitarian, he was invited by the government of Japan to analyze the deficiencies of their health services and recommend improvements. He introduced health services in Java, helped improve the medical schools of the country then called Siam, and visited Abyssinia (now northern Ethiopia) in an attempt to eradicate yellow fever.

In 1921, Dr. Heiser returned to the Philippines under the aegis of the Rockefeller Foundation. He discovered that health services had deteriorated badly in the seven years since he left. Smallpox was rampant again, for few of the young children had been vaccinated. Investigation proved that official records had been falsified to show they had been vaccinated. He faced the discouraging prospect of repeating work he had considered finished. During the next half a dozen years, the doctor and his staff painfully mended the broken threads of their earlier work, until at last they had raised health services to the earlier level.

In 1927, Victor was named associate director of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation. For the next seven years, he continued his wide travels and varied duties, tracking down and stamping out many of the diseases that afflicted mankind. Then, on October 31, 1934, Victor Heiser wrote to the president of the Rockefeller Foundation, requesting to “have the necessary steps taken to place my name on the retired list.” He was 61 and felt that he had, after 16 trips around the world, seen enough of it.

His resignation accepted, Victor sat down to write the story of his life and work. An American Doctor’s Odyssey was published in 1936 and, to Victor’s immense surprise, became a best-seller that was translated into 14 languages. “Mine has been an extraordinarily happy and satisfactory life,” he concluded, sounding for all the world like a man content to live in peaceful retirement for the rest of his days.

But an active person like Victor Heiser does not long find satisfaction in retirement. In 1938, at age 65, he accepted a position with the National Association of Manufacturers as consultant to the Committee on Health and Working Conditions. He continued in his new career in industrial medicine for another quarter of a century. Then he retired for a second time in 1963 at age 90.

There were other changes as the doctor embarked on his “second life.” He had been a bachelor, explaining in his book, “Such a career as mine has necessarily deprived me of close family ties, and many other experiences which enrich our lives.” However, in Dr. Heiser’s new life, such sacrifices in the name of a career were no longer necessary. On April 20, 1940, Victor Heiser married Marion Peterson Phinny, a 44-year-old widow. Marion, who was 23 years younger than her husband, was from a family prominent in the tobacco business. The Heisers had a country home in the beautiful hills of Litchfield, Connecticut, and they divided their time between there and New York. In 1939 and 1941 he wrote two more books for a popular audience, setting forth his beliefs in the importance of hygiene, proper food, and exercise. He was a member of the board of directors of the New York Post-Graduate Hospital until 1949, and in 1948 he was elected president of the New York Society of Tropical Medicine.

Marion Heiser died in 1965 at age 69. Victor Heiser continued his active life alone, arising each morning at 6:30 for his daily regimen of exercise—knee bends, pushups, and, later in the day, a two-mile walk. Then he got on with his work of compiling a history of the Rockefeller Foundation and writing his memoirs.

But inevitably, Victor Heiser’s long and immensely useful life drew to an end. The tall, vigorous man suddenly found he no longer had the strength for his daily walks from his Manhattan apartment. On February 27, 1972—22 days after he began his 100th year—Victor G. Heiser died peacefully.

The good doctor’s fight against mankind’s most cruelly afflicting diseases did not end with his death. By his will, Victor Heiser created a fund that provides for research in leprosy and tuberculosis.