“Wizard of the Reins” drove trotting horses to victory; his wife cheered him on.

Thomas W. Murphy (1877-1967)

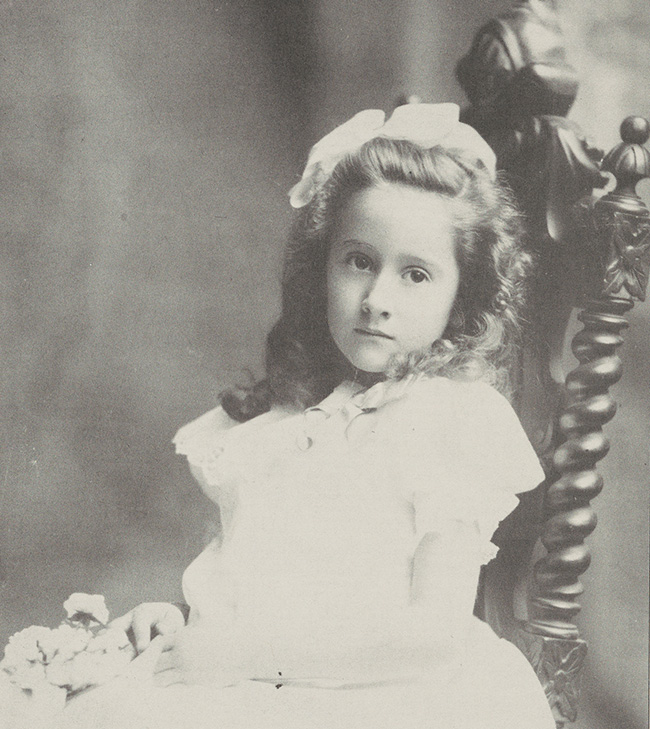

Florence Tobey Murphy (1895-1983)

They said he was to harness racing what Babe Ruth was to baseball, what Jack Dempsey was to boxing, and what Bill Tilden was to tennis. Ultimately, he became so famous he could receive letters addressed to “Thomas W. Murphy, United States of America.” And it all began with a goat.

Toward the end of the 1800s, when legend has it that Commodore Vanderbilt drove his champion trotter Maud S around the dirt roads of New York City, a little boy in Glen Cove, Long Island, lay in bed with typhoid fever and pneumonia.

A friendly neighbor brought over a goat as a “get well” gift. Tethered to a pole outside the boy’s farmhouse window, little Tommy Murphy’s gift goat gave him the will to get well. As his strength slowly returned, he sat up in bed and with the harness and reins attached to the bedposts, pretended he was driving.

In a few weeks, the skinny little boy was out driving his goat through the pastures. Later, Tom Murphy said, “That goat received more care and better training than any goat that ever lived.”

Soon he learned to break cow ponies shipped in from the West for sale. When a half-mile track was made in a plowed field, a neighbor asked Tommy Murphy to ride his horse in the first race on the new track. The horse was Bartholdy, and Tommy Murphy won easily, launching a career of winning consistently. He was still in his teens when he got a job riding a lead pony at the yearling sales at the old Madison Square Garden. With his pay, he put a down payment on a filly that had taken his eye.

After training his first mare, which he bought for $125, she was sold at a handsome profit for $1,500.

Known for his ability to make champions out of apparent failures, he began as a teenager with a pacer named Doctor Dewey. “He was a cross-fire,” Murphy once explained, “that is, when he sped up, he cut his near front foot with his off hind foot by crossing the latter under him. The railbirds joked about the lemon I had until I pried off some of his near front hoof and lightened the shoe on it, then held back the off hind foot a little by adding some weight on its shoe. That cross-fire became a good race winner.”

In his 20s, Murphy was asked to train a pacing mare named Hetty G. after two poor seasons and a reputation as a quitter, a poor feeder, and generally “track sour.” After experimenting, Murphy discovered a feed formula that whetted the mare’s appetite and when race time came, she was a trim, eager mare who won 10 of her 13 starts. With a new plan for her workouts, which included not jogging her for several days after her races and never working her between races, she went on to take 11 wins out of 11 starts in the Grand Circuit.

In 1905, Murphy took over the training of a pacing stallion named Locanda just a week before a major race. The horse was considered outclassed and out worn. Murphy took him to the blacksmith and had his bar shoes and pads changed from 11 ounces to .5 in front and 7½ behind. During the second heat, Murphy guided his mount to the inside, slipped through a narrow opening at the rail and led him to victory by a head.

In 1912, sportswriter Tom Gahagan wrote: “For spectacular reinsmanship, no driver in the country has anything on Tommy Murphy, the young wizard from Poughkeepsie. It is a sight to fire-the-blood of a lover of racing to see Murphy pull out at the seven-eighths pole and set sail for a heat. His arms are raised high in the air, his head is thrown back, while with the reins he ‘reefs’ short and sharp, keeping his horse well in hand. He is a past master in the art of using the whip without shifting the reins or losing his hold; the whalebone snaps sharply but there is none of the ‘haymaker’ swing; his mount is well in hand all the time.”

And the “Wizard of the Reins” raced them to what became known as a “Murphy finish.”

Described as “the hardest working trainer in the history of harness racing,” Murphy was the first at the track in the morning and the last to leave at night. Always training a large stable during racing season, he rode mile after mile in morning workouts and then drove in practically every race all afternoon.

Described as “the hardest working trainer in the history of harness racing,” Murphy was the first at the track in the morning and the last to leave at night. Always training a large stable during racing season, he rode mile after mile in morning workouts and then drove in practically every race all afternoon.

As spectacular as his style and success in the sulky was his uncanny ability to detect championship potential in an untried green horse or yearling. Once asked what he saw in a particular colt to make him buy him, Murphy reflected for a few minutes and then said, “I saw nothing I didn’t like.” The colt set a record as the first 2-year-old pacer to win in 1:57.

A.B. Locke, another great trotting sportsman, said about Thomas Murphy: “There have been many great trainers and equally as many great drivers, but there have been comparatively few that have combined the qualities of both these accomplishments. Patience, it is said, is always found in the makeup of a good horse trainer. Aggressiveness is the stock of the agile race driver. Patience and aggressiveness both abound in the nature of this man.”

One October afternoon in 1927, a young driver approached Murphy at a race in Atlanta and asked, “Tom, would you drive this colt for me in the fifth? Henry Knight, his owner, has never won a race and I know you could do it for him.”

The field of 2-year-olds swung into the stretch, and the slight, erect, 50-year-old man pulled Red Aubrey in against the rail behind the leaders. A tiny opening appeared, and Red Aubrey shot through it to come flying home a winner.

Thomas Murphy brought the colt back, climbed down slowly and walked toward the grandstand. “There’s your winner,” he said. “And that’s all for me. That was my last race. My swan song. I’m all through with it now.”

At the announcement of his retirement in 1927, a poem was published in the Horse Review, titled “A Plea to T.W. Murphy.”

Tell me China’s all united

Tell me Russia’s getting tame,

I’ll believe it, but that story—

Murphy’s quit the racing game?

Of course, retirement for Thomas W. Murphy never meant being away from horses, and he very shortly accepted an offer from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney to take charge of her Greentree Stable. By his third year, he had posted 111 wins, 96 seconds and 63 thirds, among them Twenty Grand, winner of the Kentucky Derby and the Belmont Stakes in 1931.

No wonder people said the W in Thomas W. Murphy stood for World Records and might as well have stood for Winner. In addition, according to sportswriter Elizabeth Rorty, “Thomas W. Murphy was engaged in improving the breed for nearly sixty years. The great stallions and mares that he developed and made famous on the track, who got their chance at breeding because of him, are foundation sires and maternal cornerstones of today’s Standardbred. It would be very difficult to find a modern champion who doesn’t carry the blood of a Murphy champion—and most of them go back to Murphy pupils over and over again.”

In retirement, Thomas Murphy was active in the stock market, and he had a desk at a prominent Wall Street firm. But he never lost interest in the world of trotting. When Thomas was 73, Leonard Buck, owner of Allwood Stables, persuaded him to come out of retirement to return to racing and work for him. The following year, Thomas Murphy picked a group of yearlings at the Lexington and Harrisburg sales, and molded them into a steady stream of Allwood winners. Within four years of his return, the big bay trotter, Kimberly Kid, became “horse of the year,” and in 1956, The Intruder won The Hambletonian, one of the most prestigious events of the harness racing season. Thomas Murphy topped even those successes at the age of 81 by buying a yearling named Bullet Hanover, considered one of the all-time greats of pacing horses, that, as a 3-year-old, became the world’s fasted pacer.

After Thomas Murphy died at age 90, the trustees of the Harness Racing Museum and Hall of Fame in Goshen, New York, elected him an Immortal to the Hall of Fame. Sportswriter Rorty recalled him this way: “With keen intelligence and that uncanny horse sense unimpaired despite his years, he was respected and admired wherever he went. But there was another Murphy, a kind and generous man to those who needed his help, and many a horseman down on his luck went on to success because this man helped him over a rough spot.”

Throughout his long life, Thomas W. Murphy enjoyed the rare privilege of doing what he loved best most of the time. He also enjoyed a warm, loving marriage and the devoted support of his wife, Florence.

In a way, charity brought them together. Murphy was spending much of his time in Poughkeepsie in order to use a famous racing site there, Rupert Park, as a training track. Although he was a horse driver and trainer and she was the young daughter of a socially prominent Poughkeepsie family, they met not at the track or at a party but in an effort to raise money for the Red Cross. In 1918, Murphy, whose racing silks were red, white and blue, volunteered to stage a day of racing and donate the proceeds.

Florence Tobey, daughter of the newspaper owner and active member of the Red Cross Women’s Ambulance Corps, was everywhere at once, organizing the event that was to be called Murphy Day, replete with banners and a parade. Some say they met on the steps of the post office. Yellowed newspaper clippings reflect the excitement:

“The many Poughkeepsie friends of Thomas W. Murphy and Miss Florence Tobey were surprised to read Sunday of their marriage in Brooklyn on September 16 last. Announcement of the wedding was made by Mrs. Arthur G. Tobey, mother of the bride.”

Another newspaper story shortly after that was headlined: “No Wonder Murphy Wins.” In part it said:

“No wonder Tommy Murphy, the sensational driver of the Grand Circuit, is doing most of the winning this year. He has an inspiration more potent even than the purses. For doesn’t Mrs. Tommy Murphy, his bride of a few weeks, sit in the grandstand and join considerably in the applause following victories of her famous husband . . .

“Mrs. Murphy sits in the grandstand close to the judges’ box and knits most of the time. But whenever Tom is making a strong finish down the stretch, she forgets about the knitting in her enthusiasm. And at the beginning of every race, Tom always looks up for the wave of the hand, which is the best sendoff he can possibly think of.”

And so it went for all the years they were together. When the Murphy children, Thomas W. Jr., Alfred T., and Oliver A. Murphy were born, Florence Tobey Murphy stayed home to care for them while her husband was traveling the Grand Circuit.

Raising three sons was not always easy, but Florence’s delightful sense of humor saw her through. She remembered, for instance, the time a neighbor’s greenhouse was pelted with stones. The three young Murphy boys were prime suspects for all the broken glass. The parents gathered the boys together for a cross-examination. They quickly discovered that sons one and two were guilty, as suspected. The youngest one, still a tot, sadly confessed: “I am sorry. I didn’t break any of those windows, I just couldn’t throw stones far enough. But I tried!”

Their gracious, rambling house in Poughkeepsie was known for its warmth and hospitality among sportsmen.

In a tribute to her late husband, given by the Dutchess County unit of the American Cancer Society 10 years after he died, Florence Murphy attested that it was “good living and hard work” that made him so successful.

“He never smoked or drank,” she said. “He was up early in the morning and went to bed early at night. And he knew a lot about horses.”

Of all the eloquent descriptions of Thomas Murphy, that probably said it as well as any, for Florence was known for her unpretentiousness. When she died at age 88 in September 1983, a Poughkeepsie minister, Bert E. McCormick, said in his eulogy:

“As you know, Florence Murphy had every right to be assuming, to claim a place of importance . . . especially in this community. After all, she grew up here . . . home-bred, so to speak. Then, too, her maiden name, Tobey, was known throughout Dutchess County, as her father owned the Sunday newspaper and was a popular editorialist. In addition, she later married a man . . . a very gentle man . . . who became world famous in what he did. And finally, her philanthropy, which she kept as anonymous as possible, was exceedingly generous.

“As I said, Florence Tobey Murphy had every right to claim a place of importance in this community and beyond, but she didn’t. Rather, she lived a totally unassuming life. Why? Because that was her style, and that style became the hallmark of the Poughkeepsie Murphys.”

Summing up, the minister said:

“Florence Murphy had a special appreciation of the comical in life. To put it simply, she had a happy outlook on this world. Of course, this world is not all happiness, especially after one passes four score years. At that time, the bitter is often mixed with the sweet, or, as someone has said, ‘Old age is like licking honey off a thorn.’ But even as the pain of her arthritis increased and the range of her mobility decreased, Florence Murphy was cheerful, optimistic, a good sport, a joy to be with.”

Clearly, both Thomas and Florence Murphy got a lot out of life—and gave back as much and more. To memorialize them and that special spirit they shared, their sons established the Thomas W. and Florence T. Murphy Fund in The New York Community Trust, to be used for charitable purposes.