Brooklyn bank teller for half a century was among the first to cross that bridge.

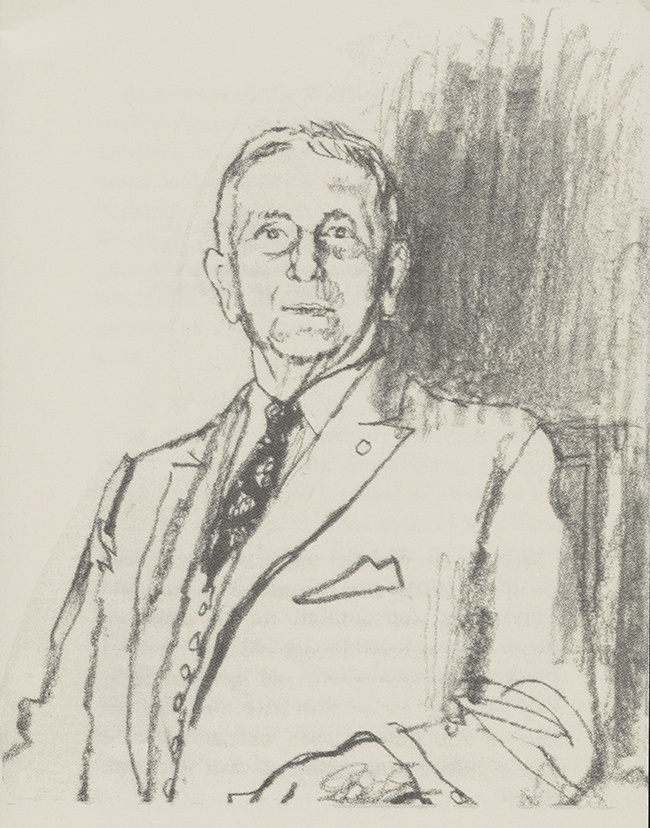

Seymour B. Wurzler (1870-1963)

Seymour B. Wurzler lived his life modestly and circumspectly. He worked long and faithfully for the same employer from boyhood through old age. He saved prudently, invested wisely, and spent carefully. And he made certain that after his death the fruits of a lifetime of labor and care would be used to help a wide variety of charitable institutions.

Seymour, known as Simmy to his family, was born in Brooklyn on December 18, 1870. He often joked that he was “a Christmas present” to his parents, Joseph and Christina Wurzler. Both of them had been born in Germany, had come to America as youngsters, and had settled in Brooklyn with their families.

Brooklyn in those days was a rural community, not yet a part of New York City. But that remoteness was soon to change, for the year of Simmy’s birth was also the year construction began on the Brooklyn Bridge, linking Brooklyn and Manhattan. Simmy was 13 when Washington John A. Roebling’s famous and controversial bridge was completed. Like other young boys of his time, he grew up believing that Roebling was a “mad wizard.” But that did not lessen his excitement on the sunny May Day in 1883 when President Chester Arthur arrived amid the clang of bells and the boom of cannons to make the first crossing of the bridge with New York Governor Grover Cleveland. With his family and friends, Simmy watched the spectacular display of fireworks during the evening. Then he joined the throngs of people who lined up to pay a penny toll for the privilege of being among the first to walk high above the East River when the bridge opened to the public at midnight.

That same year, a young man named Charles Ebbets took a job as bookkeeper for an obscure Brooklyn baseball club. The bookkeeper eventually became the owner of the club and built a baseball park for his team in the wilds of Brooklyn. As Ebbets Field and the “Trolley Dodgers” of Flatbush Avenue became part of the Brooklyn scene, Simmy Wurzler faithfully followed the team’s fortune and enjoyed his hometown’s incredible stories about “Uncle Robbie,” the team’s legendary manager, Wilbert Robinson. Simmy lived to see the name shortened to the Dodgers and eventually watch his ball club become world champions.

Simmy was a true Brooklynite, and he did not often leave his native borough. Why should he, when there was so much happening right there?

Soon after Joseph Wurzler settled in his adopted country, he took a job with the newly established Dime Savings Bank. When Simmy was 16, he followed in his father’s footsteps and quickly earned a reputation as a loyal and disciplined worker at the bank.

When New York was immobilized and virtually isolated after the three-day Great Blizzard of 1888 that produced the deepest snows in its history, the slight, wiry 18-year-old was one of three Dime employees who managed to get to work. He delighted in telling how he had tunneled through drifts well over his head, and how he had helped shovel the snow away from the door so bank customers could come in. Few made the effort, but Sim took great satisfaction in knowing he was there to serve any who might come.

As a teller, the position he held during most of his career, Sim took the financial transactions of each Dime depositor very much to heart. This was particularly true during the Depression, when apple sellers hoped for customers on the corner outside the bank and when lines for the soup kitchen wound past his door. He fretted when one of the bank’s customers came in to withdraw funds. If the amount exceeded $200, Sim would first count out the bills himself, then take the money to another employee for verification. Being cautious, he didn’t trust himself in dispensing such a large amount. Being a saver, he preferred to see deposits, not withdrawals.

As a young man, Seymour Wurzler married Elizabeth Kusch, also a Brooklynite of German descent and eight years his junior. They spent many quiet and pleasant years together before Elizabeth died suddenly on August 30, 1921, at age 43.

Two years after his wife’s death, Sim’s mother died, followed a year and a half later by the death of his father. Sim spent a number of lonely years before he met Louise Boelger Anderson, the widow of a Brooklyn physician. Soon they were married.

Louise Wurzler came from a well-to-do family. Her sister recalled that Louise, an independent-minded girl, had once been offered a “position” and wanted very much to accept it. But their father had been adamant in his refusal. “None of my girls will go to work,” he said. So, Louise had reluctantly remained at home, like other well-bred young ladies of her day.

As mistress of the Wurzler household, Louise won a reputation as an elegant cook and an excellent hostess among brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews—both her own and her husband’s—who were frequent guests. Relatives remember her as “a very quiet, refined person” and recall admiring the lovely home that was in perfect accord with the personality of its owners: always in modest good taste.

The Wurzlers enjoyed short trips together, often spending brief summer vacations at the Indian Queen Hotel in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. Near the end of his years of service at Dime Savings, the bank and some of his fellow employees sent Sim and Louise, along with Louise’s 88-year-old mother, on an expense-paid trip to Yellowstone National Park. But, typically, the habits of a lifetime were too strong. Before the vacation was over, Sim had taken his family home to Brooklyn and was back at work in the teller’s cage for the rest of his holiday.

On July 1, 1938, Seymour Wurzler received a fond and respectful send-off from the bank. An elaborate banquet celebrated the occasion. Friends and co-workers of a lifetime and some of the bank’s highest officers came to pay tribute to the faithful employee. As his beaming wife looked on, glowing testimonials were rendered to Sim’s years of service. The story of the Blizzard of ’88 was told one more time. Then came the climax of the banquet: the presentation of the traditional gold watch. That watch was an object of great pride for the rest of his life. When he retired, Sim was 67 and had worked at Dime Savings Bank for 51 years.

Louise Wurzler died on December 14, 1947, at age 74. Except for the cat that he kept for company, Sim, then 77, was very much alone. His life was simple, determined by old patterns. He took weekly drives to Louise’s grave in the Lutheran Cemetery in Queens. In summer he occasionally went to Vermont, always returning with cans of maple syrup for his friends. He frequently visited Dime Savings, where he ate lunch in the bank’s dining room and caught up with the news from his former colleagues. He stopped in often to see his wife’s sister and brother, who still occupied the grand old 12-room family homestead in Brooklyn. He called on his neighbor, a lawyer, for advice.

Nephews and nieces visited and kept an eye on him. They saw him gradually become more of a recluse and less able to maintain his home and care for himself. Eventually they arranged for their uncle to enter a nursing home. He was 92 when he died in North Tarrytown, New York, on January 2, 1963. His estate was divided among a number of charities whose services he admired, including a bequest in The New York Community Trust so he could continue to serve his fellow man for years to come.