From corsets to real estate, Latvian immigrant built a life and a legacy.

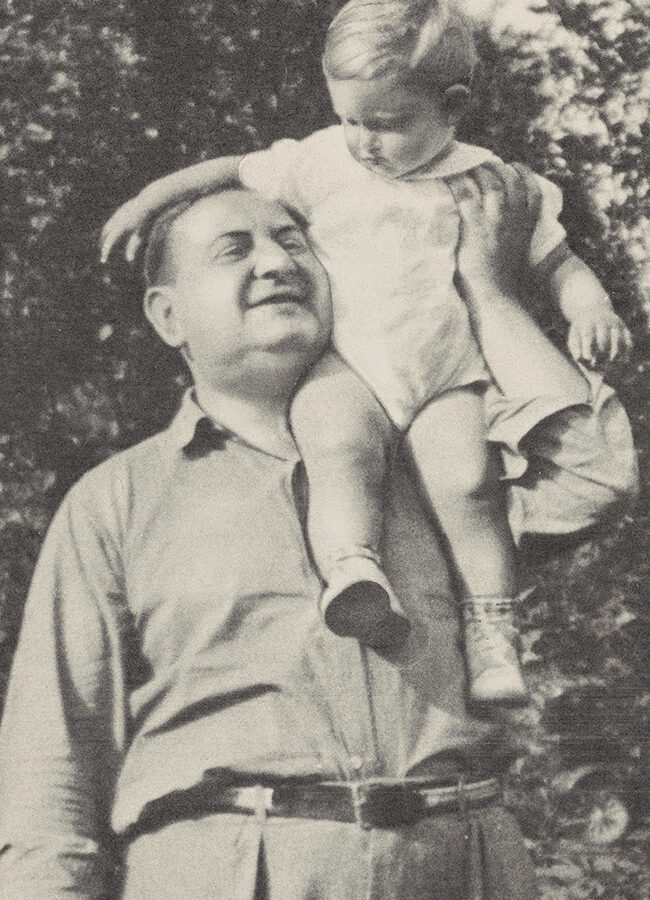

Samuel Sacks (1886-1972)

Its narrow, cobbled streets lined with gabled dwellings, Riga, the capital of Latvia, was a beautiful medieval city when two of its citizens, Hannah and Moses Sacks, welcomed the birth of their son Samuel on January 15, 1886. Although Latvia had passed into Russian hands in the 18th century, it was dominated by German merchants and landowners. Not until a year before Samuel was born did Russian replace German as the official language. Jews were, of course, a minority.

The Sacks family lived in a suburb of Riga, an important port on the Baltic Sea, a leading industrial center, and a hub of Europe’s timber trade. Moses worked hard to support his family as a schochet, a kosher butcher for the Jewish community. Samuel joined four brothers in the Sacks family—Abe, Harry, Paul, and Irving—and while Samuel was still very young, a sixth son, Carl, was born. With such a family dependent on him, Moses Sacks made the decision that thousands of others had made: to forsake a comfortable home and secure trade for the promise of a better life in a new country.

Leaving Hannah and the boys in the safety of familiar surroundings, Moses struck out alone, first for London and then for the United States. It was about 1890 when Moses arrived in New York, full of hopes and dreams. The reality of living in the New World was more difficult than he had imagined, but soon the former butcher had immersed himself in a completely new line of work: He became a jewelry peddler, traveling from city to city. It was a fine way to get to know his new country, as well as make a living. Within two years, he was financially secure enough to send for Hannah and the children.

Life was a struggle, but in time it brought its rewards. Raising their sons, Moses and Hannah emphasized the virtues of hard work and diligent study, both for the love of learning and as a way to a more prosperous life. They were excellent role models for their children. Within a few years, Samuel and his older brother Paul were following their father’s example and traveling about the country selling furs. The other boys were growing up, too, and establishing themselves. Abe became an optometrist and Harry a watchmaker. Paul and Irving eventually started successful retail businesses. Carl, the baby of the family, was the only one who seemed not to have the Sacks flair for business, but he had something that was valued at least as highly: musical talent. Carl became a violinist.

Meanwhile, when Samuel was about 21, he met Minna Leah Zirinsky, who worked as a saleswoman in a corset shop. Samuel and Minna were married on March 14, 1908; Sam was 22, and Minna was 20. Almost immediately, they decided to open their own retail corset shop at 1874 Third Ave., near 103rd Street, in New York. They were an ideal combination. Minna had the perfect personality for selling—warm, outgoing, and honest; Samuel, congenial but less intimate, already had demonstrated his acumen as a businessman. Working together, they established a chain of seven corset shops supplied by their own factory, which adjoined the original store.

The business was their way of life. For many years, they lived in an apartment behind the store on Third Avenue so they could take care of the shop and supervise the manufacturing from early in the morning until late in the evening. With the apartment so close, they spent much time with their two children, Sylvia, born March 10, 1910, and Mervin Joseph, born three and a half years later, on October 24, 1913. And after they closed the shop for the day, the family usually visited Sam’s older brother, Harry, the watchmaker, whom Sam had always greatly admired.

With the business prospering and the children growing up, Sam and Minna decided to move, and in 1924 they left the apartment behind the shop and settled in more ample quarters on Riverside Drive. A few years later, when the business no longer occupied their attention for 12 to 14 hours a day, they acquired a summer place in Saddle River, New Jersey, to escape the noise and heat of New York City. Ten years later, their son away at college and their daughter off on her own, they moved one more time, to 5 West 86th Street, within sight of Central Park. The good life, for which Moses Sacks had left Latvia, was theirs.

But it did not last. Minna died July 3, 1938, at age 50. They had been married for 30 years. Sam grieved, but eventually he set aside his grief and threw himself into his work. In addition to the corset business, Sam became increasingly involved in real estate investment and management and financial investment as well. And the intellectual curiosity that had been a hallmark of the Sacks family continued to show itself. Sam Sacks made it a practice to read The New York Times, almost cover to cover, every day. And he maintained his lifelong interests in classical fiction, history, and drama.

Sam’s Jewish heritage was rich, but his beliefs had moved away from his Orthodox upbringing toward the more liberal thinking of Reform Judaism. He greatly admired the oratory and leadership of Stephen S. Wise, one of the foremost leaders of Zionism and Reform Judaism, who had pressed for labor reforms and relief of refugees among other good works. For 25 years, Sam was a member of the Free Synagogue Wise had founded in 1907 and where he was the rabbi. Later Sam joined Congregation Emanu-El and its Men’s Club.

One of the organizations Samuel Sacks was deeply involved in was the Jewish Chautauqua Society. Organized in 1893, it was based on the original Chautauqua movement, a program of adult education that offered summer courses in the arts, sciences, and humanities. By the middle of the 1920s, most of the smaller Chautauqua organizations had disappeared, and the big, commercial Chautauqua had ended its circuits. The Jewish Chautauqua Society, however, continued fulfilling its original intention of bringing a better understanding of Jewish faith and traditions to Christians, offering programs at various Christian universities, placing reference books in college libraries, offering the study of Judaism in depth to college students, reaching teenagers in summer church and Boy Scout programs, and communicating with the general public with award-winning films in theaters and on television.

Despite his business activities and community and religious involvement, Sam realized he was, at age 54 and in the prime of life, a lonely man. It was then that he met Rhonie, a 51-year-old widow, who also had a grown daughter. Sam and Rhonie were married on September 3, 1940, and Rhonie fitted easily into the role of companion and business assistant.

Again, Sam’s life was rich and full. But 10 years later, tragedy touched his life again. His beloved daughter, Sylvia, died suddenly of a heart attack at age 40, on November 4, 1950.

But Sam, blessed with good health and abundant energy, again accepted his grief and learned to greet life with enthusiasm. Although the corset business was disposed of in his later years, Sam continued with his real estate and financial interests, demonstrating by his shrewd investments that his acumen was not diminishing with age.

Like many successful businessmen of his time, Sam Sacks was politically conservative, and had often argued with his more liberal, college-age son about Franklin D. Roosevelt, whom he referred to as “that socialist.” But Sam was an enormously generous man, who gave of himself as well as of his fortune. He made substantial contributions to charity, usually in the form of memorials, which was his way of perpetuating the names and memories of those he felt closest to.

In 1960, his philanthropy found expression in the incorporation of the Self Improvement Clubs of America to recognize exceptional achievement of individuals and organizations.

The Samuel Sacks Achievement Awards grew out of this concept. They were designed to recognize achievement in arts and letters, education, sciences, religion, and public service. Sam’s bequest to The New York Community Trust established the Samuel Sacks Fund to carry out his charitable interests.

On June 4, 1972, Rhonie, his wife and partner for the second half of his life, died at age 83. A few weeks later, on June 30, 1972, Samuel Sacks died at age 86, having realized his parents’ dream in another time and another place.