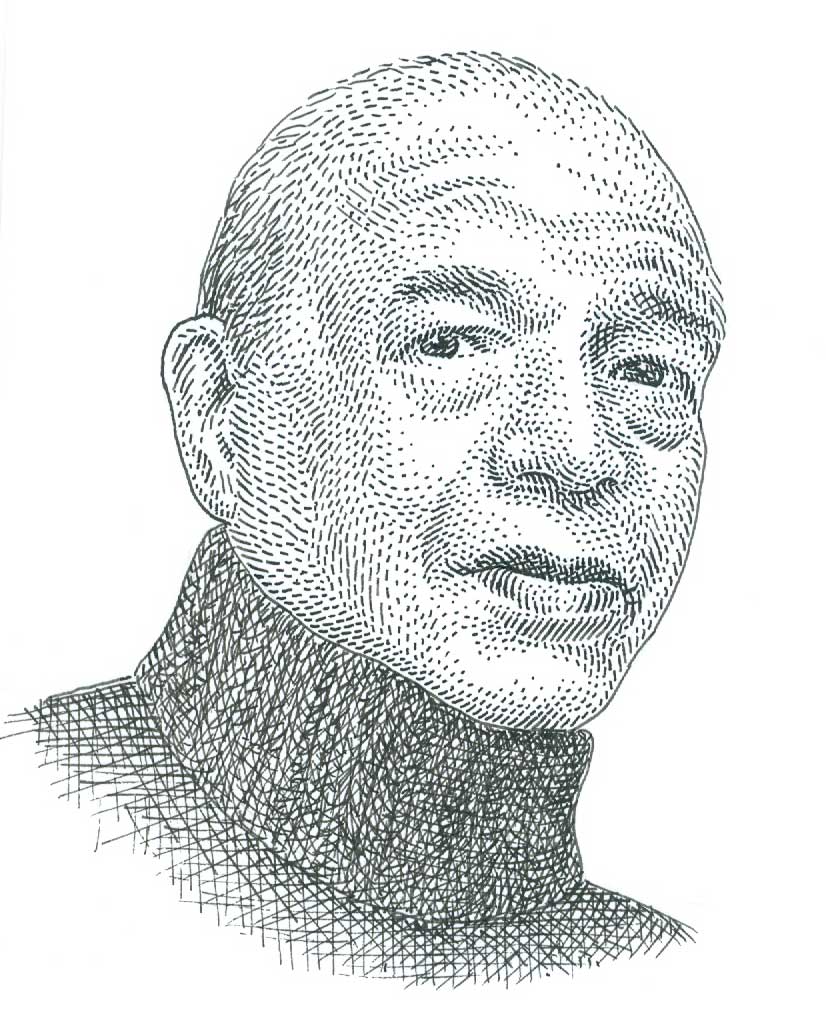

A dedicated advocate for the LGBTQ community. Today, his generosity supports LGBTQ youth and elders in New York.

Sam Wilner (1916-1996)

In Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill where he lived for three decades, Sam Wilner was a local landmark. Tall, nattily dressed in tweeds and his trademark dark beret, he was a familiar figure in this neighborhood of stately old brownstones. He was not one to chat up the neighbors along State Street, but those few he came to know over the years respected and appreciated this clever, cultured, impatient, and crusty man. Neighbors agree that Sam left his imprint.

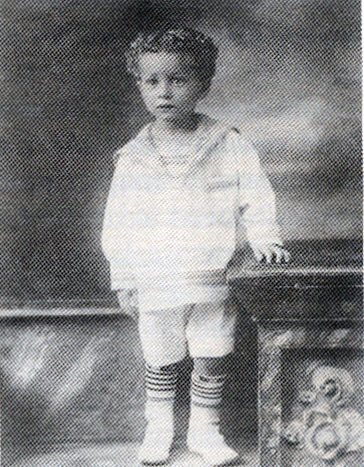

He talked little about his early life. He was born in the Bronx on March 4, 1916. In summer, his mother ran a boarding house in the resort area of the Catskills and he remembered the long trips by train and then by horse and buggy. His father had been in the Russian Army, made his way as an immigrant by sewing shirts, and later owned a factory. Sam’s confidants had the impression that the parents were stern and the childhood was not a happy one. There was a half-brother but the two were estranged; an effort to reconcile them late in their lives did not work out.

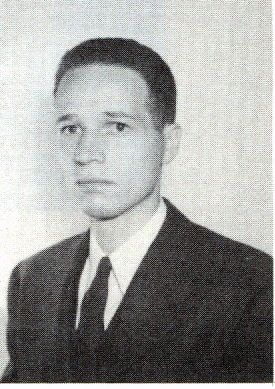

Sam studied science as an undergraduate at the University of Kansas and then went on to earn a master’s degree in business administration at the University of Michigan. A tour in the Army Air Force provided further specialized training, this time in statistics at the Harvard Business School. His military career took him to Italy where he served with a heavy bomber group. From 1946 until 1964, he was assigned to military installations in the United States and also in Germany, Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, and Korea, where he worked on management surveys.

The years in military service were difficult for Sam, observes Bruce Patterson, who later supervised Sam when he volunteered at Gay Men’s Health Crisis: “Coming out of the closet was not an option for gay men and women in those times.” When Sam was mustered out with an honorable discharge, he returned to the United States and began a career in administration, serving for several years at a juvenile detention center. Then he went to work in the City University budget office, where he remained until his retirement 15 years later.

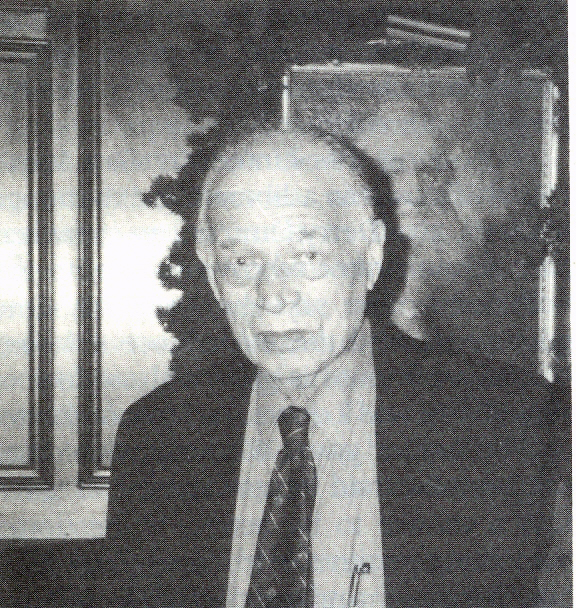

In 1968, he and his longtime companion, Ted Rifkin, bought a brownstone in Boerum Hill, one of the 150-year-old homes on State Street, claimed by residents to be “the greenest block in Brooklyn.” Sam and Ted shopped for antiques and art to fill their new home. They tended their garden and gave dinner parties where Sam showed off his talent for French cuisine-especially desserts. When Ted died in 1984, the home suddenly seemed big and empty. Ted, an English teacher by profession, has been the gregarious one and the pair had enjoyed the theater, visits to museums, and entertaining their friends. Abruptly, Sam now had to develop a new lifestyle.

He did it by throwing himself into volunteer work for the first time in his life. He became a dedicated worker at Gay Men’s Health Crisis in Manhattan, the organization that had helped Ted cope with AIDS and his failing health. As a volunteer, Sam spent eight or nine hours weekly on the “hotline” advising callers about services and did peer counseling. He also joined a local Brooklyn group, Touch, which served weekly dinners for people with AIDS.

Becoming a volunteer at Gay Men’s Health Crisis was a liberating experience for Sam, says Derry Duncan, an organization administrator who worked with the volunteers. She says he gave his time generously and the experience enabled him to work out his grief without fear of stigma. “He was a doer… a let’s-cut-to-the-chase kind of guy.” Working with other seniors who had experienced loss gave him a chance to be active, to be doing something positive, she maintained, adding, “It gave him a sense of empowerment.”

Sam came to the organization before AIDS increased to epidemic proportions and, in those early years, manning the telephone hot-line was an opportunity to deal directly with distressed callers in a personal, advice-providing manner. But soon calls would increase to 40,000 yearly and the volume as well as advances in medicine led to the development of an array of new services. To help callers, a computerized service was created, but Sam never really adapted to the change requiring callers to determine their needs by pushing buttons instead of taking his directions. Though he continued his volunteer work, the new computer system was not for Sam.

Probably the clearest snapshot of Sam comes from one of his own letters: “I am an ordinary looking guy, six feet one inch, about 175 pounds, blue eyes, graying, thinning hair… I don’t have any mental hang-ups, am fairly even-tempered and easy to get along with. However, if I feel I’m being wronged, I’ll fight for my rights and persist till I win.” Some folks would quarrel about Sam’s claim to an even temper, says Timothy Walther, Sam’s neighbor and executor. But it would be hard for anyone who knew Sam well to dispute his claim to being a realist, self-described as having “a low level of tolerance for fools and stupid people.” In Mr. Walther’s words, “Sam didn’t own a pair of rose-colored glasses.”

Sam always had a head for figures and his business acumen served him well: he made a fortune from investments. Lacking close relatives, he determined to leave his wealth to gay organizations and established the Sam Wilner Fund in The New York Community Trust to support programs benefiting gay youth, including scholarships, and elderly gay persons, male and female.

Sam died on November 9, 1996, at age 80. “I still feel his presence,” says Mr. Walther. In Sam’s last months, when cancer sapped his strength, his neighbors took turns pushing his wheelchair so he could take in favorite outdoor sights and street fairs, blowing his whistle imperiously to clear a path among the crowds—still nattily dressed in his tweeds and his trademark dark beret.