She was a translator who fought the Nazis with words; her husband escaped them.

Ruth Norden Lowe (1906-1977)

Warner L. Lowe (1899-1986)

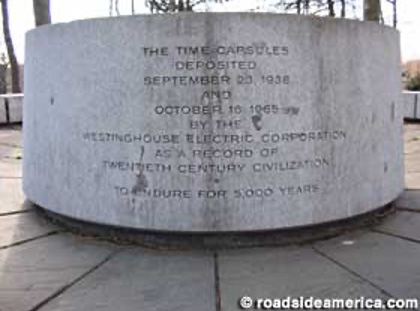

In December 1937, Albert Einstein sent Ruth Norden a telegram in German, praising her translation of his letter destined to be sealed in a time capsule created for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The letter is titled “Einstein Hopeful for Better World,” and the time capsule is addressed to inhabitants of Earth 5,000 years in the future.

“You have done a great translating job,” Einstein wrote in the telegram, “and it is factually better than the original. His telegram sold at auction in 2023 for $10,625. According to Swann Galleries, the auction house, Ruth was responsible for many of Einstein’s English translations, but translating was just one of the many jobs she juggled.

Ruth Norden was born in London in 1906 to Julius and Hermine Norden—he was Christian, she was Jewish—and she had one brother, Heinz, who also was a translator. Together they translated about 60 books.

After World War I broke out, her family returned to Germany, where Ruth worked as a publisher from 1930 to 1934. She immigrated to the United States in 1934. From 1935 to 1942, she was a journalist and editor for such publications as The Living Age and The Nation. She became an American citizen in 1940.

After the U.S. entered World War II, she was editor-in-chief of the Radio Control Section of the Office of War Information in Washington, D.C., a federal agency documenting America’s mobilization for the war effort. There, she was responsible for programs broadcast to Germany and Austria.

In February 1946, she returned to Germany and took a job as a control officer—she was one of four American supervisors of 80 German staff members—for Radio in the American Sector (RIAS), initially called Drahtfunk in the American Sector (DIAS). The station became a leading source of culture, education, and political enlightenment for those in West Berlin and a political instrument against the Communists.

Ruth was promoted to director after two months. With municipal elections approaching in October 1946, RIAS embarked on a get-out-the-vote campaign. Ruth was committed to neutrality in news reporting, which she learned from the Office of War Information, and RIAS provided complete, impartial reports of the municipal election returns. But her tenure as director, which ended in December 1947, was not a happy one. She and her political editor, Gustave Mathieu, were repeatedly accused by fellow occupation officers and RIAS journalists of aiding the Communist cause.

Both Ruth and Gustave believed that inter-Allied cooperation was essential to German reconstruction. In September 1947, she wrote to a friend, “I don’t feel that we are really accomplishing our goal with the occupation much as I would like to say that we do.” She said there was anti-Russian feeling so rampant as “to make one feel uncomfortable.”

Her contract was not renewed: One account had her a victim of anti-Communist hysteria, while another claimed she had failed to pay RIAS’ bills.

In 1952, she married a cousin, Dr. Warner L. Lowe, in Manhattan.

Ruth became an associate editor of the American Journal of Psychotherapy in 1959 and worked there until her death in 1977. The Journal’s editor, Dr. Stanley Lesse, called her “a rare person by any standard.”

“If I ever had a disagreement with Ruth,” Dr. Lesse wrote, “it was over her desire to return an article to a contributor for additional clarification or extra corrections. Our biggest conflict,” he added, “would occur in relation to our ‘Smiling Psychiatry’ section.”

She often turned jokes into proper English. He wrote. “I would plead, ‘Ruth, these characters … in our jokes are not Oxford Dons; they really aren’t sharp. Please let them make some grammatical errors.’ ” And sometimes she would.

Warner was born Werner Lester Lowenstein in Berlin, Germany, one of two sons of Max Lowenstein and Beila Lowenstein. He appears to have worked in publishing in Berlin before fleeing the Nazis by way of Havana, and then Miami in 1936. He moved to New York in 1937. Following his World War II service, he received a BA in 1947 from the University of Denver, a master’s degree in 1958, and a PhD in psychology in 1951.

He was an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology from 1951 to 1953 and coauthored a study of the religiosity of Protestant students at the University of Denver.

From 1953 to 1954, he was the chief clinical psychologist at the Glens Falls Mental Hygiene Association in Glens Falls, New York.

He then became assistant director of the Alfred Adler Mental Hygiene Clinic in Manhattan. Alfred Adler was an Austrian psychotherapist who founded the school of individual psychology, which emphasized the importance of the inferiority complex to personality development. Warner wrote articles on psychology in the 1950s and 1960s, including several on Adler’s ideas.

The couple lived in Greenwich Village. Ruth died in 1977, and Warner died in 1986.

Ruth and Warner’s unrestricted fund at The Trust helps many nonprofits improve life in our region while keeping their legacy alive.