Lawyer, Yale professor, and negotiator built a legacy with his French wife.

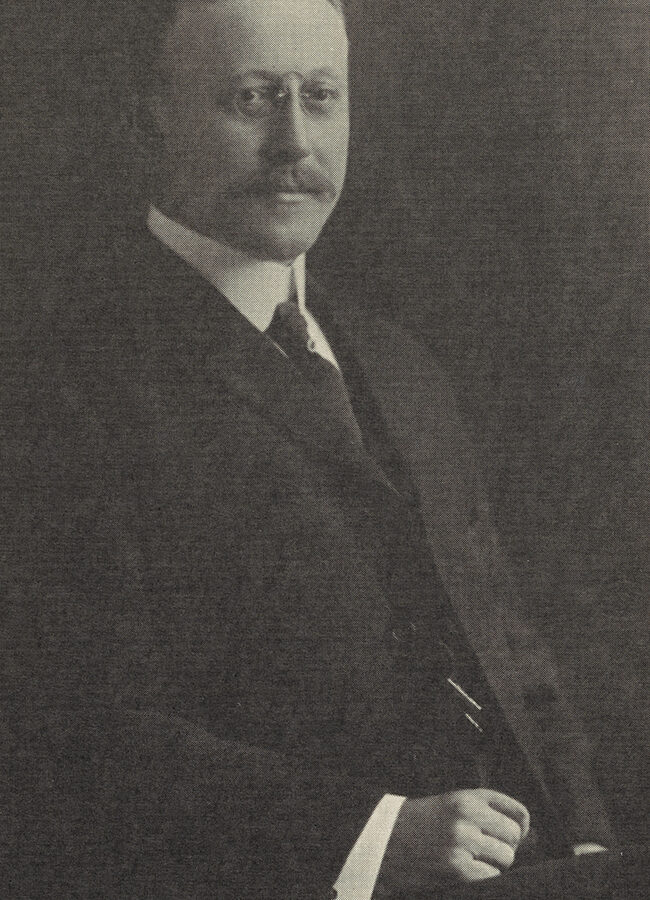

Robert Clark Morris (1869-1938)

“Truly we as a community had reason to remember the father. Now as a town we have reason to remember the son, and proud are we indeed of the name we bear.”

These words, written by the town clerk of Morris, Connecticut, in 1859, were addressed to Dwight Morris, the son of James Morris for whom the town was named, in thanks for a gift of books. Three-quarters of a century later, the town had reason to remember the grandson as well, when Dwight Morris’ son, Robert Clark Morris, presented the town with a museum in honor of his ancestor and a reading room in memory of his wife. It was a gesture typical of a man who was proud of his heritage, yet modest about his own spectacular career.

Robert Clark Morris was born on November 19, 1869, at “Lindencroft,” the family home in Bridgeport, Connecticut. He likely inherited from his New England ancestors the character, intellect, and sense of responsibility that marked both his public and private life.

The Morris family emigrated from Wales and first set foot in the New World in Boston in 1637. A later branch was established in New Haven, Connecticut, and a son of that line, James Morris, moved in the early 18th century to the western part of Connecticut, settling in a section of Litchfield known as the Ecclesiastical Society of South Farms.

James Morris had a son, also known as James, who was born and grew up in South Farms. Intending to become a minister, he studied privately, then attended Yale and graduated in 1775. Somehow, he was sidetracked from his original purpose and taught school until the Revolutionary War broke out. Commissioned a captain, James Morris fought in battles on Long Island, in White Plains, and Germantown. While he was with Washington’s troops in Pennsylvania, he was taken prisoner and held “three years and three months, lacking one day,” according to his memoirs. Freed during a prisoner exchange, Captain Morris rushed back to South Farms to visit his parents and marry his sweetheart.

The Revolution over, James Morris went back to teaching. He had an extensive library that he opened to intellectually curious children of his town. His generosity aroused the disapproval of some citizens, who brought charges against him for “disturbing the peace of the church.” They believed such exposure to book learning could only result in “blowing up the pride” of the young and making them “feel themselves above their mates and feel above labor.” The charges were later dropped when cooler heads prevailed. And by 1803 the townspeople had undergone so complete a change of heart that they built an academy for Morris. It drew students not only from local areas but from surrounding states and abroad as well. Because the curricula of Morris Academy were equivalent to what most colleges were offering at the time—and because those colleges did not admit women—Robert Morris later described Morris Academy as “the first co-educational institution of higher learning in the United States.”

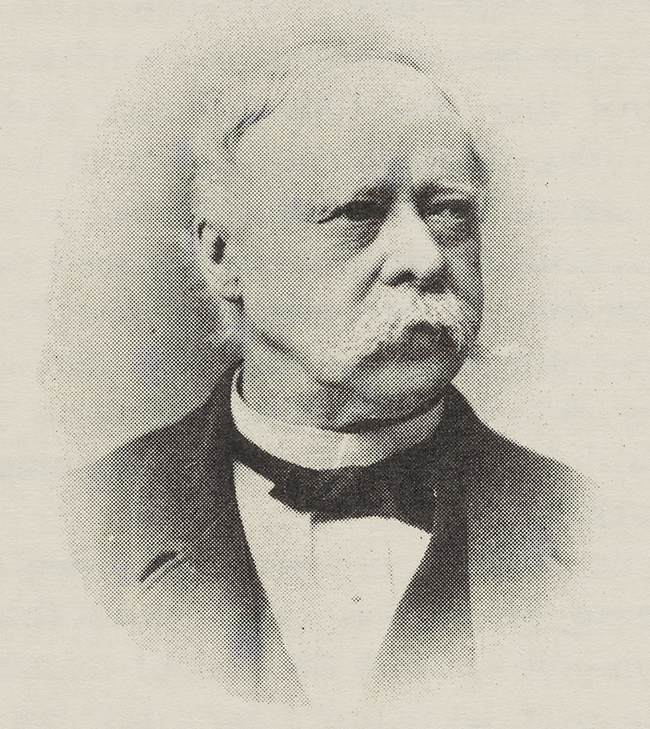

Though he was 61 when the War of 1812 began, James Morris was soon back in uniform with the rank of colonel. When the war was over, he returned for a few last years as an educator. By now a widower, he remarried, and at age 66 had a son, Dwight Morris, who was to be the father of Robert Clark Morris. James Morris died in 1820, when Dwight was 2 1/2 years old.

In 1859, descendants of the people who had once accused James Morris of breach of the peace decided to break away from the town of Litchfield. The center of that town, where meetings and elections were held, was more than four miles away—much too far to travel in those days. Besides, their taxes were being spent to maintain roads and bridges they claimed they never used. So, they organized a new town and named it Morris after the academy and the man who had brought fame to their area.

Meanwhile, Dwight Morris had grown up to become a prosperous Bridgeport lawyer who did his share of public service. A colonel in the Civil War, he later declined President Abraham Lincoln’s offer to be appointed federal judge for the Territory of Idaho but served in the U.S. Consular Service in France and was secretary of state for Connecticut. Contemporaries apparently found him impressive. One who knew him said, “His personal appearance was striking, his figure erect, and he carried himself with a military bearing. He was courtly, dignified, yet genial and well beloved by his friends and companions.” Another said, “There is a charm in his old-time affability and courtesy that cannot be described. But few public men in the state possess more fascinating ways.”

In 1869, 10 years after the town of Morris was founded, Robert Clark Morris was born to Dwight Morris and his second wife, Elizabeth Clark Morris, 27 years his junior. Like his grandfather, he had a high regard for education and combined teaching with his law career. Like his father, he became a talented lawyer who preferred appearing before the bench rather than on it, for he declined two judgeships. Like them both, he had a strong sense of patriotism, but he showed his talents as a penman rather than a military man.

Robert Clark Morris graduated from Yale with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1890 and was admitted to the Connecticut Bar the same year. Before going into practice, he continued his studies on both sides of the Atlantic. Then, with two additional degrees and a period of study in Europe behind him, he established an office in New York City. After practicing privately for several years, he joined Swayne, Swayne, Morris & Fay, and soon after became senior partner in a succession of firms bearing his name. When Morris, Plante & Saxe was dissolved in 1937, he became associated with Delafield, Marsh, Porter & Hope until his death.

During his nearly 50-year career, Morris handled a variety of interesting legal assignments. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to the United States and Venezuelan Claims Commission in Caracas, a delicate diplomatic situation in which the United States acted to bring about an amicable settlement of claims pressed by European powers against the financially unstable Venezuelan government. After World War I, President Warren G. Harding assigned him to a similar position before the Mixed Claims Commission of the United States and Germany. It was his responsibility to present claims of the United States and its citizens against Germany for satisfaction of financial obligations under the peace treaty. In his two years of service, he surveyed, classified, and initiated formal action on 12,416 separate claims aggregating close to $1.5 billion.

Morris also was involved in the case of Paul Bolo, known as Bolo Pasha, a notorious French traitor of World War I. Bolo had persuaded Germany to hand over millions of dollars to be used to influence the French press in favor of a German peace. In the spring of 1916, Bolo stayed in New York while he made secret connections with the German ambassador in Washington. When the French government became aware of Bolo’s activities, it appealed to the governor of New York for evidence. Ten days of intensive work by the New York state attorney general, to whom Morris served as counsel, turned up sensational disclosures of Bolo’s treachery that led to his arrest and execution in Paris.

Other assignments were perhaps less exciting but showed Morris’ versatility. Banking authorities asked. him to study a series of private bank failures. The state of Missouri retained him to go before the U.S. Supreme Court to challenge the authority of national banks to conduct branch banking. And he was named to a commission to establish a New York City subway route. Morris also was active politically. As president of the Republican Committee of New York in his younger days, he led the fusion ticket that overthrew formidable Tammany Hall opposition and swept city offices.

Throughout Robert Morris’ busy career, he carefully reserved time for teaching and writing. For nine years, he lectured at Yale Law School on French law. For eight more years, he taught international arbitration and procedure and published a textbook. Later, he took government and citizenship as his theme for two more years of lectures. Altogether, he taught at Yale for 19 years.

As time went on, he wrote and published a number of books and pamphlets. “The Pursuit of Happiness” discussed the powers and opportunities people can exercise in their government to maintain stability in private business. Others expressed his support for the U.S. position in World War I.

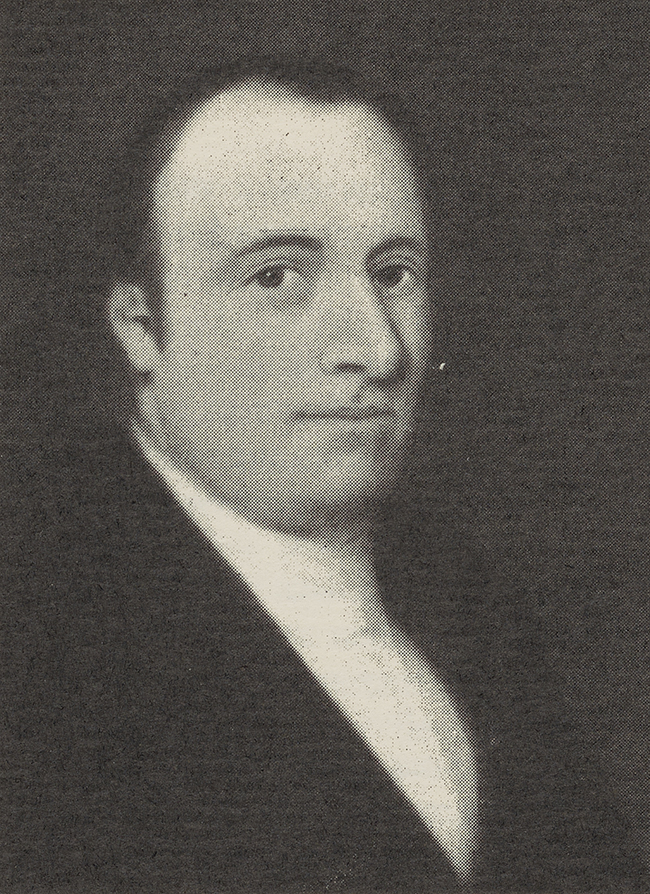

In 1931, when Robert Morris was 62, he married a vivacious, 44-year-old French woman (his first marriage had ended in divorce). Convent-educated in the manner of the day, yet dissatisfied with the limited perspective of such schooling, Aline Brothier read avidly and traveled widely in a successful effort to broaden her education. During World War I, she worked in a Paris hospital treating tetanus victims. She then came to the United States. Fascinated by American history and government, she continued her informal studies. Eventually she became a U.S. citizen, observing along the way the “very decided tendency” on the part of native-born citizens to relegate naturalized citizens to second-class status. This was wrong, she insisted—naturalized and native-born must feel equal and be treated as equals.

Her friend Robert Norwood, rector of St. Bartholomew’s Church in New York, called her “my little fighter.” Others described her as having “a way of bringing those to whom she was speaking to a fair consideration of her point of view and was usually successful in winning them over to her way of thinking.” She persuaded a major political party to carry on her fight against bias toward naturalized citizens as a political project—and the other major political party immediately followed suit. The efforts of Aline Brother Morris, later continued by Robert Morris himself, did a great deal to improve the status of naturalized citizens.

What must have seemed to their friends a brilliant match was destined to be short-lived. On October 6, 1932, only 17 months after their marriage, Aline Brothier Morris died. Six years later, almost to the day, Robert Morris died a month short of his 69th birthday, on October 13, 1938. They had no children.

During his last six years, Morris must have been impressed many times by his place in a chain of human events. In January 1935, he traveled to the quiet little town of Morris, Connecticut, where his own roots lay deepest. There he dedicated the James Morris Museum and the Aline Brothier Morris Reading Room, filled with family heirlooms and personal books. A newspaper reporter who recorded the ceremonies seems to have been aware of the coincidences. Referring to James Morris and Aline Brothier Morris, she wrote, “And so two lives, more than a century apart, are united, not only in family relationships but through their impact upon, among other things, the bigotry of who will or will not be educated and who is or who is not qualified as a whole American.”

A colleague wrote, “The two interests closest to the heart of Robert C. Morris were his profession and his country, and where his heart was interested, he was always ready to bear his share—and more than his share—of responsibility. This characteristic united with his remarkable vigor, his ability, and his character in bringing to him positions of high honor and service, which he filled with distinction.”

It might be added that awareness of his heritage and pride in the name he bore helped mold Robert Clark Morris into the man he was.

The Robert Clark Morris and Aline Brothier Morris Fund in The New York Community Trust