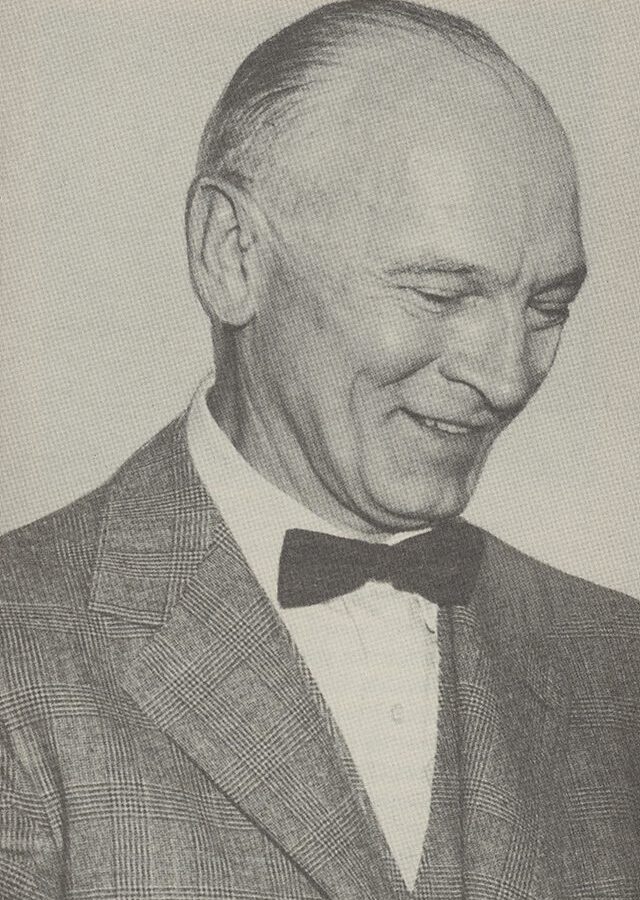

The first Director of The Trust, led the institution for more than 43 years.

Ralph Hayes (1894-1977)

“I’m going to college.”

The Hayes family, seated around the dinner table, turned its attention to the youngest member. The year was 1911. The family wasn’t wealthy, and none of them had ever gone to college. But it was a family that had survived multiple tragedies: the death of their mother and six brothers and sisters. Those who were left were very close, and they listened attentively to Ralph’s startling announcement.

They were, in fact, still getting accustomed to his new name. Christened Alphonso Lamont and called “Babe” by his affectionate family, the youngest Hayes child had decided in high school that Alphonso didn’t suit him. So, he changed his name to Ralph, keeping the A as a middle initial. This was the same child who, still too young to attend school, had waited impatiently every day for the newspaper to arrive so he could read the sports section. The family had long recognized Ralph’s brilliance. Maurice, 39 and the eldest, nodded. Nora, the oldest sister who had brought Ralph up from the age of 2, agreed. So did Paul and William. Ralph would go to college, and they would do what they could to help him.

In the years that followed, Ralph showed himself to be a student of the first rank and a gifted executive whose career took him to the office of the Secretary of War in Washington, into the motion picture industry, into publishing and banking, to the top echelon of The Coca-Cola Co., and to the position of director and major guiding force of The New York Community Trust.

Ralph Hayes was born in Crestline, Ohio, on September 24, 1894, the son of a railroad engineer. The tracks of the New York Central had been laid in 1851; two years later, the cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad arrived. The junction of these two great railroads, Crestline became the change point for east and west passengers, crews, and freights. The first engine that steamed into Crestline, at an average speed of 15 miles an hour, burned wood cut from the forest along its right-of-way. A century later, Crestline was considered one of the most modern railway facilities in the world. Locomotives were serviced in the roundhouse that covered acres of ground, and freight cars were rerouted along miles of tracks that crisscrossed its yard. As railroading boomed, so did Crestline, a pleasant town with solid brick houses and an air of prosperity.

Ralph’s mother, Margaret Hayes, 10 years younger than her husband, was only 17 when she gave birth to her first child, Maurice, in 1872. By the time Ralph was born, 22 years later, there were six sons and four daughters in the family. But the two youngest had died of diphtheria in early childhood. Ralph was their ninth living child. Two years after his birth, a double tragedy struck: A baby born August 1, 1896, lived only 11 days. Margaret, knowing she was desperately ill and heartbroken by the losses she had endured, begged her children never to marry. (None ever did.) Two days later, she died at age 42. Nora, the oldest daughter, was only 20 at the time, but she took responsibility for running the household and caring for the younger children.

Life was lonely for John without Margaret. A few years after her death, he remarried and, leaving his family behind in Crestline, moved to Columbus with his new wife, where in 1902 a daughter, Lauretta, was born.

But still the family could not escape death’s hand. In 1906, 1908, and 1909, three more Hayes children died, all of them in their 20s. When Ralph announced his determination to go to college, only a sister and four brothers were there to listen. But they backed him all the way. Ralph left for Western Reserve University in Cleveland wearing a new suit Maurice had had tailored for him. And then death struck the Hayes family three more times: In April 1913, Ralph’s father was killed by a train in the railroad yards. Less than three months later, Maurice died at age 41. And just at the time of Ralph’s graduation, his brother William died, also at age 41. Now only John, Nora, Paul and Ralph were left.

Ralph had to work hard to support himself in college, but he distinguished himself, nevertheless, both academically and socially. He gained a reputation as an excellent speaker, a talent he continued to exercise throughout his long career. And whenever he got involved in a student activity, he wound up running it. In 1915, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree and a Phi Beta Kappa key. He was not quite 21.

Ralph liked Cleveland and decided to stay there after graduation. He got a job as secretary for the City Club, an organization of prominent men who met to discuss public issues. Frequently, important speakers were invited to address the Club. One of them was Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, who had once had a law practice in Cleveland and had served as its mayor. Ralph oversaw arrangements for Baker’s speech. When the two met, Baker was immediately impressed with Ralph’s intelligence and pleasant manner, and promptly invited him to become his private secretary.

So, in June 1916, Ralph Hayes went to Washington. It was an exciting, challenging time to be in the office of the Secretary of War, for the country was teetering on the brink of involvement in World War I. As private secretary to the Secretary of War, Ralph Hayes was responsible for an office of 14 people, all but two of them older than he was. Furthermore, half of Washington was knocking on Baker’s door, and it was up to Ralph to decide when to say “yes” and when to say “no”—and how to say it. It was a position perfectly suited to Ralph’s executive and diplomatic talents. His natural tact and courtesy enabled him to get along well with everyone, regardless of age or rank. The author of an article about Baker’s super-secretary, published in The American Magazine, commented: “I have heard it said that there are only three men in Washington who can keep a secret, and Hayes is one.”

Meanwhile, the United States went to war. In July 1918, declining a commission, Ralph Hayes enlisted in the Army as a private. Sent to Ligny, France, he was soon commissioned a lieutenant. He continued to act as an aide to Newton Baker, traveling with him on an official American Expeditionary Forces inspection party. From December 1918 until March 1919, Lt. Hayes served as liaison officer with the American Commission to Negotiate Peace at Paris. He later drew upon his wartime experiences to write “Secretary Baker at the Front” and “Care of the Fallen: A Report to the Secretary of War on American Military Dead Overseas.” He also edited Bakers book, “Frontiers of Freedom.”

Ralph Hayes returned from France and was discharged in May 1919. He returned to Baker’s office, and the following February he received a temporary appointment as assistant to the Secretary of War.

Newton Baker had a tremendous influence on Ralph Hayes’ life. When Woodrow Wilson appointed Baker to the cabinet in March of 1916, Baker was a pacifist; ironically, it became his tremendous task to direct U.S. military operations in World War I. Baker was the target of a great deal of criticism, and ultimately his conduct of the war was subjected to congressional investigation. Finally, however, Baker was vindicated, and criticism gave way to praise.

Ralph Hayes was with Baker during those difficult years. In 1920, Ralph returned to Cleveland, the duties of his temporary appointment fulfilled. Newton Baker retired the following year to his Cleveland law practice, although he continued to be a public figure. He and Ralph Hayes stayed in contact for the rest of Baker’s life. In December 1935, Ralph wrote this letter to his former employer and mentor: “When I knocked, timidly enough, at your office door a few months less than 20 years ago to tell you how speakers at the City Club came in the rear entrance, I had no idea that, in arranging a luncheon for the Club, I was arranging a life for myself…. I shall never cease to be grateful that you took me in and so far adopted me that you have been more of parent and priest to me than anyone else I’ve known. And that has been a warming and mellowing experience. The fraternizing of relations may depend on ties of blood; that of business associates may be founded in material interest; but friendship must forge itself from the purer substance of affection. You can hardly know how much of a guide, philosopher, and friend you have been to me through these decades, but I wish I could tell you what an everlasting kindness you did a younger lad in letting him sense the essential dignity that life may have.”

After returning to Cleveland, Ralph went to work as assistant to the president of the Cleveland Trust Co., Frederick Harris Goff, who became another important figure in Ralph’s career. Goff originated the community trust idea that resulted in the Cleveland Foundation, which later served as a model for The New York Community Trust.

Ralph worked with Goff for two years. Then, in 1922, his administrative genius caught the attention of Will H. Hays, high commissioner of the motion picture industry. Hays, a former postmaster general, established the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America Inc., more commonly known as the Hays Office. “I would like to have the bank loan Ralph Hayes to the cause,” Will Hays wrote to Frederick Goff, “because of his organizational ability, his acquaintance with men and things, and just that quality of going out and accomplishing, which, of course, makes him valuable to you.” When that letter was written, Hays and Hayes had not met.

At that time, the motion picture industry was the fourth-largest in the country, and Will Hays was concerned it attain the highest possible artistic and moral standards and develop the highest degree of educational and entertainment value. The ideals were lofty. Ralph Hayes, then 28, saw the organization as a challenge.

Meanwhile, Frank J. Parsons, a vice president of the United States Mortgage and Trust Co. in New York, had heard about the success of the Cleveland Foundation and of other community trusts in major cities that had followed Cleveland’s lead. Parsons visited Goff to get advice from the best source. While he was in Cleveland, Parsons met Ralph Hayes. Not long after Parsons’ visit, Ralph accepted the assignment with the Hays office but viewed it as temporary. “I shall return to Cleveland if the bank still desires it—when this temporary service with Mr. Hays is completed,” he wrote.

But several things happened to change those plans. Shortly after Ralph left for New York, Frederick Goff died. The following spring, in April 1923, Ralph Hayes resigned from the Hays organization, accepted the position of director of the newly formed New York Community Trust, and sailed for Europe on the Aquitania to spend three months studying social conditions before his appointment was to become effective in July. At age 29, Ralph Hayes assumed active directorship of New York’s Community Trust.

In September 1927, Ralph Hayes was elected vice president of Chatham Phenix National Bank and Trust Co. in New York, one of the oldest and largest banks in the country. It was a position he held through 1929; on January 1, 1930, he became second vice president of the Press Publishing Co., publishers of the New York World, where he remained for a year as assistant to the president, Ralph Pulitzer.

Then, in 1932, Hayes joined The Coca-Cola Co. He served as secretary and treasurer in 1934 and 1935 and then as vice president until 1948. That year, he was elected a director of Coca-Cola International. He was elected vice president one year later, and in 1953 the position of treasurer was added. For the next 14 years, until his resignation in August of 1967, Ralph Hayes served as treasurer, vice president, and director of Coca-Cola International Corp., all while also serving in his full-time capacity as director of The New York Community Trust.

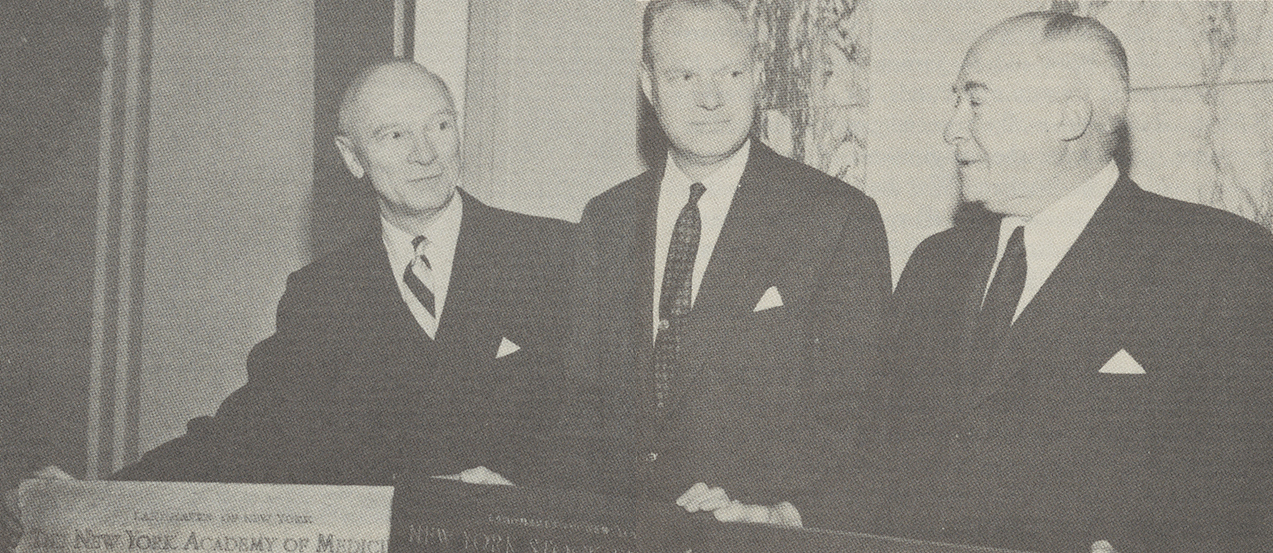

There were other directorships and other responsibilities as well: Ralph Hayes was chairman of The James Foundation of New York and St. James, Missouri; and he was president of Community Funds Inc., established in 1955 to administer small or special project funds. Furthermore, there were volunteer assignments, such as the National War Fund, established to raise and distribute money to all approved war-related appeals except the Red Cross; Ralph Hayes was appointed secretary in 1943.

Ralph was a voracious reader, a witty speaker, a tireless letter writer, a fine conversationalist, a loyal friend. A handsome man of immense charm, Ralph enjoyed the role of the much-sought-after bachelor, for, like his brothers and sisters, he never married. He lived most of his life in hotel apartments—the Waldorf-Astoria in New York and, later, after he joined Coca-Cola, the Hotel Du Pont in the center of Wilmington, Delaware.

For one brief year in the late 1920s, Ralph experimented with having a place of his own. He rented an unusual house in Greenwich Village—912 feet wide, 40 feet long, three stories high. Ralph liked to entertain friends in this tiny landmark residence, once the home of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. It amused him to send out engraved invitations phrased in a sort of Olde English: “Soon after Ten of ye clock on ye night of 26 June, Ralph Hayes will conduct a Social Pufh of some confequence, God willing . . .” When the group invited was too large for the little house, the merry band repaired to a local inn, “hoping thereby the better to improve his social fences, now in miserable disrepair.”

But Ralph was not cut out for domesticity, and he soon returned to the simpler living arrangements of hotel apartments, free from the burdens of maintaining a home. Nor did he care for possessions. Once an inventor friend sent Ralph a chair of his own design. Ralph thanked the donor, admired the gift, then gave it to the Salvation Army. Soon after, he learned that the friend was on his way for a visit. Ralph quickly called the Army and was told the chair had been sent away. A frantic search ensued, and the chair was reclaimed in time for the inventor’s arrival. But this time, Ralph got used to the chair and had it installed in his quarters at the Hotel Du Pont.

Smoothly managing a “double life,” Ralph Hayes commuted weekly between two homes and two careers. In Wilmington, he was a Coca-Cola executive who breakfasted and played golf at the country club with old friends on Sundays. In New York, he was concerned not with making money but with giving it away. In addition, he took a great nostalgic interest in Crestline, his boyhood home. Although his brother John had died in 1924, Paul and Nora still lived there. During Nora’s long illness in the 1950s Ralph was her frequent visitor. And he shared Paul’s interest in the Crestline Historical Society.

Travel was one of Ralph’s great pleasures, and London was probably his favorite city. He also enjoyed visits to the Ozark community of St. James, Missouri. As chairman of The James Foundation, Ralph saw to it that money from the fund was disbursed to the maximum benefit of the town, and he thoroughly enjoyed his involvement with the townspeople.

But of all Ralph Hayes’ pleasures, he found his greatest enjoyment in his friends. He had many, of every age, in many places, and in many walks of life. Each New Year, he sent hundreds of cards in lines of his own witty verse. No matter how busy he was, he was never too busy to write—newspaper and magazine articles, booklets and brochures, eloquent letters, and clever notes—to close friends of many years and to people he had met only once or twice.

Ralph Hayes retired as director of The New York Community Trust in 1967, just before his 73rd birthday. For 44 years, he had worked with impressive energy, dedication, and imagination to build an organization with a single, inspiring purpose: to do good. The achievements of his lifetime continue in the work he began.