Champion of Stage and Law, Shaping Justice in the Arts

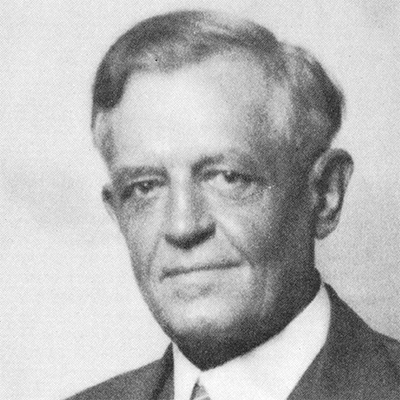

Paul N. Turner (1869–1950)

Paul Turner’s career allowed him to enjoy the best of two worlds – the dignity and solidity of the law on the one hand, and the gaiety and flamboyance of the theater on the other. As founder and chief counsel to the Actors’ Equity Association for 37 years, Paul Turner earned the admiration of lawyers and the theatrical community. Fighting for the rights of entertainers, it is said that he never lost a legal battle.

He was born in 1869, in Elgin, Illinois, the only child of Daniel Newell Turner, a railroad station master, and Sophie Prezinger Turner, the daughter of a doctor. Paul’s mother died when he was two years old, and the boy was sent to Minnesota to live with his father’s sister. Later, when his father remarried, Paul went back to live with him and his stepmother, Emma.

As a young man, Paul worked as a railroad telegrapher, saved his money, and eventually was able to go to college. After graduation from Upper Iowa College in Fayette, Iowa, he made his way to New York City, where, according to family legend, he arrived “with 5 cents and a bunch of bananas.” There he enrolled in the New York University Law School. The early New York years were ones of financial hardship and ill health. Money was so scarce in his student days that he and his roommate took turns buying the penny newspaper, shared it during their morning ride downtown to classes, and met again to exchange halves for the ride home at night.

“Perhaps the day will come when the future will be clearer, and we can part with what we have today, without worrying as to whether we will have much of anything left tomorrow.” – Paul Turner

While still in his early 20s, Paul suffered a near-fatal chest ailment that left him uninsurable. Ironically, he was never sick again until his final illness.

Alice Harcourt Fisher, a well-known actress of her day, was a cousin of Paul’s, and it was she who first introduced him to the world of the theater. She got jobs for the struggling young law student as a cook and a bartender at after-theater parties. With the combination of his own talents and her help, he managed to earn his way through school. Even after he graduated from law school and had established a law practice, he was attracted to the theater and thespians – and it was natural that many of them began to come to him for legal advice.

He joined both The Players and The Lambs, the two most distinguished social clubs for actors, and spent much of his time in the company of performers where he began to recognize the problems that actors faced and determined to do something about them. At the time, for example, many actors were not paid for rehearsal time. If a play closed after a single performance following weeks of rehearsal, the actor received only one night’s pay. And an actor in a company that closed on the road could be left stranded, with neither job nor money, in a city far from New York. As Paul learned of such problems, he became convinced that actors would have to organize and negotiate for standard contracts.

And so, according to a plaque on the wall of The Player’s library, “during the first three months of 1913, there met in this room without permission a small group of four or five men,” one of whom was Paul Turner. The outcome of the unauthorized meetings was the formation of the Actors’ Equity Association.

As Equity’s legal counsel, Paul Turner exercised considerable influence in shaping the new organization and in determining the tone and pattern of its activities. Turner was a firm believer in arbitration as the best method of settling disputes – litigation in the courts, he said, only wasted time and money. At his insistence, arbitration was included in every Equity contract proposal. Thus, at a time when most unions considered direct action as the only method for achieving their goals, Equity became the first union to stake interpretations of its contracts on arbitration.

An Equity colleague later wrote of him, “Paul Turner charted its paths in what was at the time a legal wilderness … He helped to guide Equity through its difficult formative years, and the desperate struggles which established Equity as the representative of the actors… In all the 37 years during which Mr. Turner was Equity’s counsel, it never suffered a final legal defeat anywhere, at any time.”

In the troubled years of the Thirties and Forties, Turner’s chief concern was to keep the theater alive and healthy, rather than to extract the last dollar from an enfeebled industry. He managed to forestall excessive wage and benefit demands that might have put many of the small producers out of business and made the theater an even greater risk for everyone involved.

While an undergraduate at Upper Iowa College in Fayette, Paul was a friend and classmate of Jedediah Sperry, whose family lived in Fayette. Turner was a frequent visitor to the Sperry home in Iowa and later, when the Sperrys moved to Indiana, he continued to call on them. During these visits, Paul made the acquaintance of Jedediah’s effervescent younger sister, Maude.

It was not until Paul was an established New York attorney with a flourishing practice among theater people that Maude Sperry, visiting her brother in New York, became reacquainted with Jedediah’s bachelor friend. Paul and Maude were married on June 25, 1910. A year later, the Turners had a son who died soon after birth. Several years later, when Turner was 48-years-old, their daughter Tabitha was born.

Maude Sperry Turner was a woman with a deep intellectual interest in literature and the arts. As beauty editor of a women’s magazine, Maude used her monthly column to express her rather unorthodox ideas. Her primary doctrine, “Beauty comes from within,” brought in 1,000 letters a month from approving readers and accounted for a great deal of irritation among the magazine’s advertisers of beauty products. Maude’s insistence that plain cold water was the best facial astringent did not deter Elizabeth Arden from hiring her to write advertising for her cosmetic company—nor did it deter Maude from accepting the position and then continuing to write exactly what she believed anyway.

As a couple, Paul and Maude Turner were a study in contrasts. Paul was unimpressed by the trappings of wealth; Maude enjoyed and needed them. Paul cared little about clothes or grooming; Maude was outfitted by the finest stores in New York. Paul enjoyed all kinds of people, so long as they were interesting; Maude preferred her companions to be as mannerly as she was. Paul was constantly absorbed with his theatrical cronies; Maude found many of them self-centered and their shoptalk tiresome. Paul liked to play cards and enjoyed sports as a spectator; Maude disliked both.

Because of their great individual differences, and their equally great mutual respect, the Turners devised a somewhat unusual marital arrangement: They lived in separate apartments. Paul’s was a plain railroad flat where he could cook for his friends and entertain them in informal bachelor fashion. Maude’s was a beautifully decorated penthouse.

Once or twice a week, Paul went to Maude’s for dinner, or took her out to dine. Every Saturday night he brought her flowers, and on Sunday mornings Maude and their daughter had breakfast at Paul’s flat. It was an arrangement that satisfied them both, until one day in his sixtieth year when Paul astonished his wife by suggesting that they try sharing an apartment. They did, and their new arrangement continued for the rest of Paul’s life.

The Turners shared a mutual enthusiasm throughout their marriage: the island of Nantucket. In the 1890s, Paul had started going to the island, and he began buying up land near what was then a flourishing actors’ colony. Eventually the Turners acquired a house there. It was a huge Victorian house built in the form of a cross and, they liked to say, inhabited by ghosts. Haunted or not, it was in such bad condition that one could only enter through a window. But in time, the Turners remodeled the house to create a home they both loved. They called it “Outward Bound.”

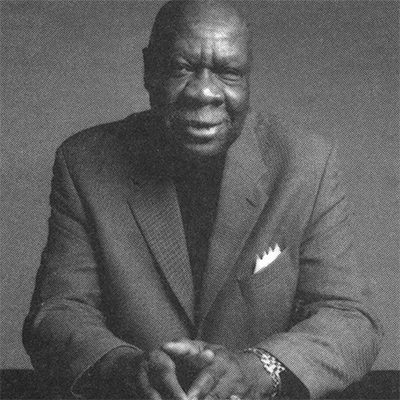

During the winter the Turners again went their separate ways. Paul made an annual habit of joining his close friend, actor Frank Gillmore, on a cruise or trip abroad. Gillmore was, to all outward appearances, just as much of a contrast to Paul as Maude was. He was meticulous, well-groomed, and tailored in obviously expensive taste, and Paul Turner was none of these. But both were persuasively charming men, and both were devoted to the theater. Frank Gillmore was also a member of the group that founded Actors’ Equity and served as its president for many years.

Although Maude was not included in the winter vacations, her influence was felt in many other areas.

“In all the 37 years during which Mr. Turner was Equity’s counsel, it never suffered a final legal defeat anywhere, at any time.” – A member of the Actors’ Equity Association

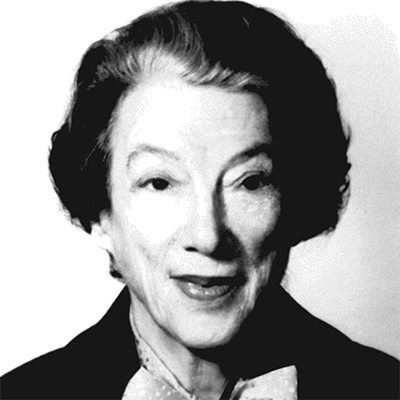

Like many men of his day, Paul wanted no part of having a woman lawyer in his office. But Maude was a feminist, and a very persuasive one. Paul yielded, and in the early Thirties he reluctantly hired Rebecca Brownstein, straight from law school and not yet admitted to the bar. He prepared himself for a wasted three months while his new assistant “looked things over,” but five days after her arrival he casually tossed a file on her desk and told her to go try the case before the Workmen’s Compensation Board.

It was the beginning of a sometimes difficult but ultimately rewarding association. Within a few years, a New York newspaper carried a story about Paul Turner and his female associate, headlined, “No Man Need Apply.”

One of Miss Brownstein’s problems with her employer was Paul’s obliviousness to his surroundings. His office was depressingly shabby. Simply because he couldn’t be bothered, it had not been painted in a dozen years.

Finally, during one of the Turners’ Nantucket vacations, Miss Brownstein had the office painted and refurbished on her own initiative. Surprised and pleased with the results, Paul wondered why he had not done it long ago. But when it later became apparent that the firm needed new quarters, his reluctance again forced Miss Brownstein to pleading and cajoling.

The new office was resplendent with new carpeting and new furniture – with the exception of Turner’s same battered old desk, piled high as always with papers. Nearly every day he ate a sandwich and an apple at this littered desk, and often he was joined there for a bag lunch by some of the most outstanding theatrical personalities of the time.

Paul Turner was known to his colleagues as a man of ideas, of bold imagination, of unconventional and sometimes annoyingly casual methods. He was also known as a man with a poor memory for names, and he was often unable to introduce the very people who lunched at his desk. He was unable to recall the name of Mary Pickford when she came to him to seek legal advice in divorcing Douglas Fairbanks, and there were those who believed he habitually called his wife “Honey” because he could not think of her given name.

His letters reflected his personality, written in his big, open handwriting. They were short, sentences were sometimes incomplete, and details were left for someone else to supply – but they always expressed precisely what he wanted to say.

He was also a man who respected the ideas of those who worked with him, and he never hesitated to admit when he was wrong.

Paul Turner was 80 when he died on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1950. He is buried in Nantucket. Turner’s early financial struggles formed lifelong habits that never changed. The man who had to share a penny newspaper in his youth preferred in his old age to walk hatless through a downpour than take a taxi and watch the fare mounting up on the meter.

Believing that he had perhaps not made the best use of his wealth during his lifetime, he had written in his will, “I request that my wife and daughter do a lot more good with what they receive than I have done. Perhaps the day will come when the future will be clearer, and we can part with what we have today, without worrying as to whether we will have much of anything left tomorrow.”

It was in this generous spirit of such words that Paul Turner established the Paul N. Turner Bequest, to be administered by The New York Community Trust for charitable purposes.