Poet-anthologist and poet-artist lived ascetically in a “cold-water penthouse.” Left legacy at The Trust for emerging artists.

Oscar Williams (1899-1964)

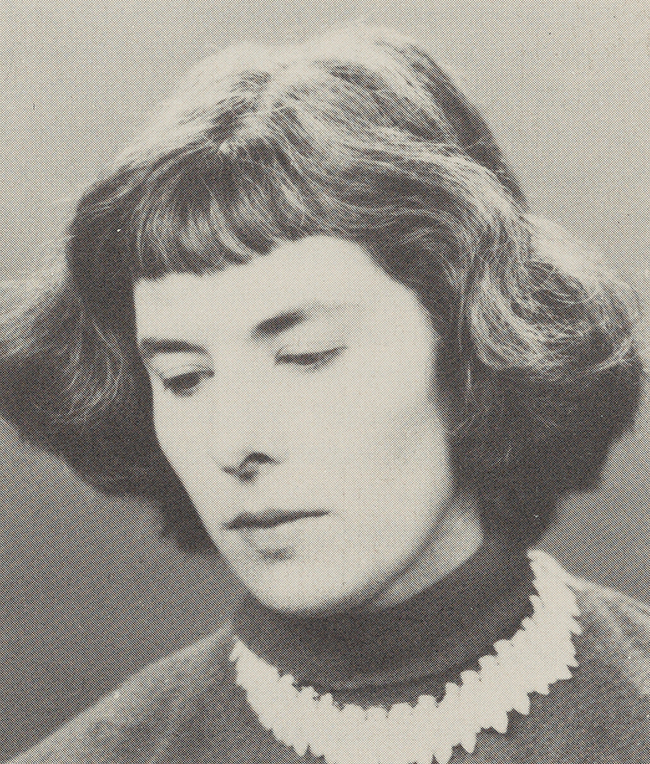

Gene Derwood (1909-1954)

“We were found by the wayside by poetry,” they said in explanation of their origins, “and we never looked back.” Oscar Williams, poet-anthologist, and Gene Derwood, poet-painter, were so absorbed in their art that they risked poverty in their everyday lives for it. Poetry propelled them forward, and their dedication to their art kept them going, even amid great physical and psychological hardships.

There were two versions of the time and place of Oscar Williams’ birth. Oscar preferred to say he was born in Brooklyn on December 29, 1900. However, his close friends and family said he was born near Odessa, Russia, into a family named Kaplan, on December 29, 1899. At any rate, Oscar’s father came to the United States in 1905 and worked in a factory by day and peddled clothes on the street at night. Two years later, when he had saved enough money, he returned to Russia and, seeing that the persecution against Jews was still extreme, brought his whole family to America. When Oscar arrived in Brooklyn at age 8, he was fluent in Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew.

Oscar’s mother died in strange circumstances when he was 14. Soon afterward, unhappy with his family life, the teenager left home to determine his own destiny. From that time on, tormented by memories of a painful childhood, Oscar Williams turned his back on his past and rarely spoke of his early years. For a time, he lived with his older sister. He spent one summer as a farmhand and another period in New Orleans as a protege of novelist and short-story writer Sherwood Anderson.

Poetry became central for Oscar when he was a student at Boys High School in Brooklyn, and for five years he wrote steadily. At age 16, he sent out a number of poems to various magazines and newspapers under his own name, Oscar Kaplan. They were all returned marked “rejected.” Then, at his sister’s urging, he resubmitted the same poems using the last name of a well-known movie personality, Williams. Half of the poems were accepted for publication. Thus, Oscar Williams’ career had begun.

That success released a virtual torrent of poetry, and Oscar’s poems began to appear regularly in such “little” magazines as Poet Lore, Munsey’s, The Nation, The Smart Set, The Midland, Contemporary Verse, Everybody’s Magazine, The Freeman, London Chapbook, Pearson’s, Grinnell Review, Double Dealer, The Bookman, Current Opinion, The Bellman, The Overland Review, and Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. Then, in 1921, a book of 62 poems, The Golden Darkness, was published by The Yale Series of Younger Poets. Soon afterward, a second collection, Gossamer Days, made its appearance.

Oscar Williams’ talent had been recognized, and he was offered a scholarship to Yale University. But, as Oscar himself told friends, he was “too arrogant to accept.” Besides, he felt attracted to making money. A pamphlet extolling the financial possibilities of the growing advertising business caught his attention and held it. Oscar had no experience in advertising, but he managed to talk his way into an executive position by proposing a unique and ultimately successful merchandising scheme. He was so successful in one of his business ventures that Congress passed a law against it for being unfair competitively. Oscar also was advertising manager for the Democratic Party of Florida in 1936. Later he would explain, “I was seduced by what is called the real world.”

For many years, Oscar was loyal to that world. Although he later said that during those years, he neither read nor wrote so much as a line of poetry, those who knew him find it unlikely that his abstinence was total. For it was during this period that he met Gene Derwood, and her influence on him was considerable.

A shy, cultured, and intense woman, Gene Derwood was talented both as painter and poet. Born in Illinois in 1909 of pre-Revolutionary English lineage, Gene had spent her early years in the Midwest and the South. While still in her teens, she moved to New York to study, paint, and write poetry. There, poet Elinor Wylie, shortly before her death in 1928, introduced the young girl with blue eyes to the thin, tousle-haired young poet. Oscar and Gene fell deeply in love, and within a short time they were married. The years of financial success soon followed, and during this period their only son, Strephon, was born on April 2, 1934.

One day in 1937, while Oscar and Gene were on vacation in Florida, Oscar was stricken by a mysterious ailment. Doctors could find nothing wrong with him, but he finally was able to diagnose his own illness: “The inner man” was compelling him to begin writing in earnest. This realization came, as he later told British poet W.H. Auden and others, while suffering one evening alone in his room he “smelled an angel” and knew that from then on, he was “doomed” to write. He yielded to the compulsion and wrote a poem. With the “inner man” released and fulfilled, the illness vanished.

Oscar sent his poem to a number of newspapers, but only a few printed it. “I realized then how good I wasn’t,” he remarked years later.

Although his low finances were a continuous problem, the late 1930s was a period of great ferment and activity for Oscar. In 1938, Hibernalia, a small collection of his poems, was published. Two years later, the Oxford University Press published The Man Coming Toward You.

Oscar also was developing an interest in other poets’ work. “I had a great deal of catching up to do,” he once told an interviewer. “There had been a tremendous outflow of fine new talent. I looked for them in anthologies and wasn’t satisfied with what I found, so I started working on my own anthology.” The result was a series of anthologies completed and published during World War II called the New Poems series and culminating in The War Poets: An Anthology of the War Poetry of the 20th Century in 1945. After that, Oscar undertook for Charles Scribner’s Sons his most famous anthologies, the Little Treasury series, which led some critics to recognize him as the best poetry anthologist in America.

Oscar Williams edited more than 30 anthologies for a number of publishers—so many that an acquaintance once rhymed, “I saw Oscar Williams standing there / With a nest of publishers in his hair.” Combined sales of his books totaled more than two million copies at the time of his death. Although Oscar’s share of royalties would have enabled him to live in greater comfort the last few years of his life, he stayed in his former apartment and clung to his unextravagant ways.

He soon earned a reputation as a man with a special genius for recognizing the genius of others. Once, when asked how he selected poems for his anthologies, he replied, “How do you pick one girl to marry? In poetry, it’s divine polygamy. Generally, when a poem stays with me for a long time, that poem delivers the goods.”

Oscar wielded considerable power in the small, brilliant world of poets and poetry, and he used this power gracefully and even-handedly. He was a practical man with an unerring sense of what the poetry-reading public wanted and the sensitivity to bring them the best poetry of the time. Ambitious poets of all ages flocked to him, and although he enjoyed their company and their adulation, he remained fair- minded and honest, able to separate his feelings about a poem from his feelings about the poet. Among the many whose work he encouraged and anthologized were John Berryman, Richard Eberhart, R.P. Blackmur, Robert Lowell, Muriel Rukeyser, Dylan Thomas, Stephen Spender, and Karl Shapiro.

Oscar Williams also was a perfectionist. In addition to the demanding work of selecting poems for the anthologies, he insisted on taking on many of the details of producing the books. He determined the layout of each page, so the lines would fall just where he wanted them. Oscar pasted the dummy pages in place. And he once telephoned a publisher in the middle of the night, unable to sleep because the slipcase did not fit the book perfectly.

Meanwhile, Oscar wrote poetry of his own, and Gene wrote and painted. They did not share the same approach to poetry. Gene’s poems came to her in intense creative bursts. She rarely made revisions in her writing. She did not believe that poetry or painting were subjects one should study or be tutored in, and she let her talent follow its own bent. Oscar, on the other hand, believed that poetry was an exceedingly difficult craft, and he worked hard at it. Generally, Gene Derwood’s poetry is regarded as the more lyrical as well as the more traditional. But many consider Oscar Williams’ poetry more original, with its emphasis on fantastical imagery of modern city life that presents a vivid, if somewhat depressing, view of 20th-century man. Oscar himself believed that Gene Derwood was “touched by the diamond.” He regarded her as the foremost female poet of her time, and he cherished and protected her so her genius could flourish.

Although much of the literary world made the climb to the Oscar and Gene’s “cold-water penthouse,” as he often called it, few were allowed to become intimates. One who was admitted was Dylan Thomas, the young Welsh poet whose great talent and problems with alcohol were equally legendary. When Thomas visited the United States to give poetry readings, Oscar and Gene were among his personal friends, and Oscar served as Dylan Thomas’ poetry agent in America. And Thomas was one of Gene’s favorite subjects to paint. Of the more than 150 paintings she produced, some 20 were portraits of him.

Gene Derwood had always been an intense, cerebral woman whose health was delicate. In 1954, she had surgery for cancer of the stomach, and a week later, she died. She was 44. The death of the woman he loved and the artist he idolized catapulted Oscar into profound grief. He was desolate, but he struggled to take up the threads of his life without her. He worked on anthologies as he had before, with great attention to the smallest detailș. Though there was no longer any financial pressure, he continued to travel to speaking engagements. And he never ceased to worship the memory of Gene Derwood.

Writers and artists who lived in New York still flocked to his interesting little apartment with its walls and walls of books, where he entertained them with anecdotes of his youth. One of his favorite stories was about meeting novelist Sherwood Anderson in New Orleans. Oscar had hitchhiked all the way there from New York to receive a poetry prize. Anderson, being quite taken with the skinny young man, invited him to stay at the estate where he himself was a weekend guest. Before the formal dinner that evening, the young lady of the house suggested her guests go horseback riding. Oscar, who had ridden one long hitch on his journey from New York in a truck that had no floorboards, now found himself on a horse for the first time. Undaunted, he contented himself with a gentle nag that moved at a harmless pace while his new friends dashed off ahead. The relish with which the city poet described himself on horseback never failed to reduce his listeners to helpless laughter.

In 1964, Oscar became ill. Friends and fellow writers were shocked when they learned he was in the hospital. Cancer of the throat was the diagnosis. The end came a few weeks after the illness struck, and on October 10, 1964, Oscar Williams died, two months short of his 65th birthday.

It is not surprising that Oscar Williams should have expressed a wish to perpetuate the art of poetry after his death, and his will granted his executor the power to carry out his wish. The executor transferred the residuary estate to The New York Community Trust, where the Oscar Williams and Gene Derwood Fund was set up for fellowships, scholarships, or grants to needy or worthy artists or poets.

“That poetry is actually the life is a faith I have” Williams wrote in his introduction to “New Poems: 1940.” “Poetry is the play eternally rehearsed; we are the actors.”

One of the play’s fine actors is dead, but through his vast efforts, the work of many others—including that of his beloved wife, Gene Derwood—found life and perhaps a touch of immortality.