Wall Streeter creates fund at The Trust to defray ancillary costs of cancer.

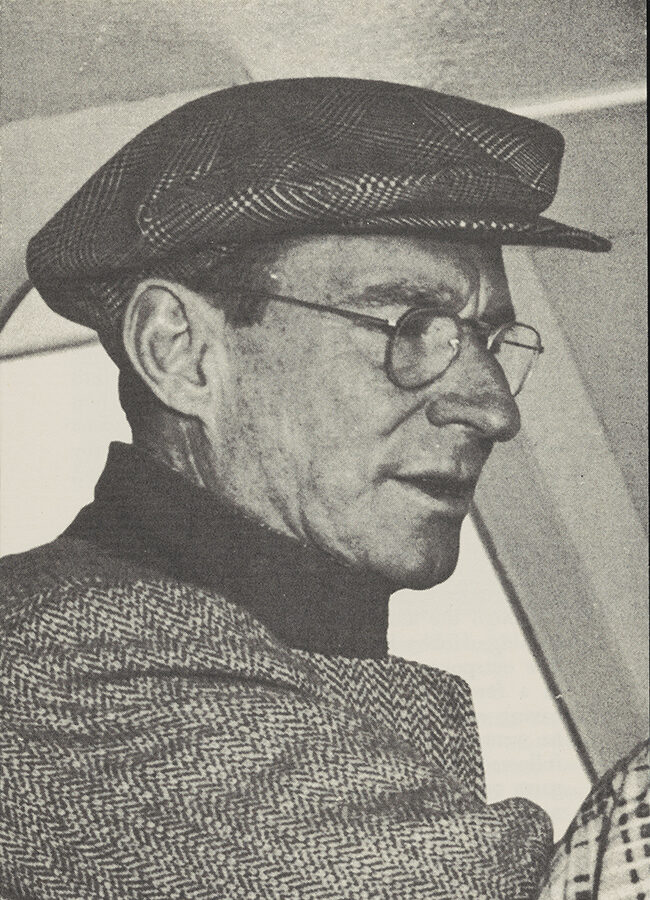

Orland Smith Greene (1894-1961)

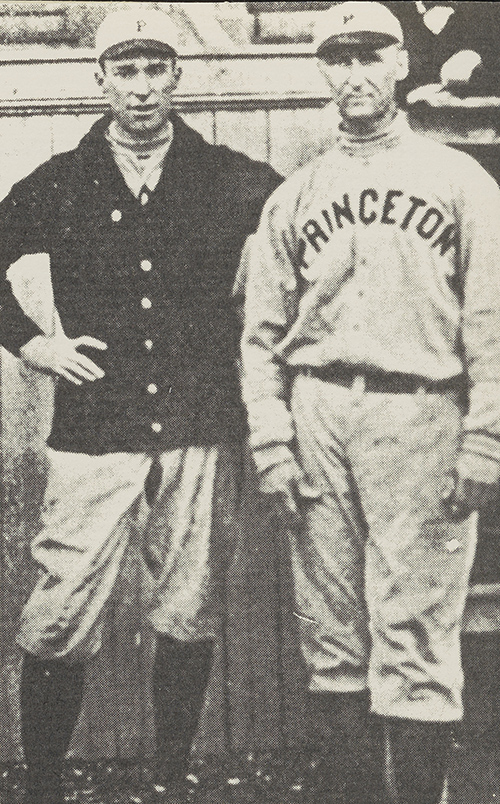

The score was tied when Hobby Greene came to bat for Princeton in the last half of the ninth inning. As captain of the team, it was up to him to beat the archrival Yale team in the last game of the 1915 inter-collegiate baseball season. Hobby swung, connected, and hit the home run that won the game.

That night, the Princeton team celebrated the victory in a New York hotel. The gang was all there including Coach Bill Clarke, to whom Hobby Greene had come to feel especially close. Although the attention was focused on him, Hobby had no liking for the limelight. The outspoken ballplayer let his admirers know, in a few terse, well-chosen words, that he was having none of their hero worship. That settled, he went on to enjoy the party. In the years that followed, his friends never let him forget that game or that evening, and he never tired of reminiscing with them.

Orland Smith Greene was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on March 7, 1894. His father, William M. Greene, was vice president and general manager of the southwest division of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. His mother was the former Jeanette Donnelly. The family, which included a brother and sister, spent several pleasant years in Cincinnati, Baltimore, and Chicago, where William Greene’s railroad business took them.

Orland attended the Adirondack-Florida School and continued his college preparatory courses at the Hill School in Pennsylvania, where he was captain of the baseball team. In 1911, he entered Princeton, and in his sophomore year earned a position on the varsity baseball team. Just under 6 feet tall, the slender, rangy youth with the long arms and fine hands proved to be at least as talented in the classroom as he was on the baseball field. ”His quick mind could make a home run before the rest of us could get to first base,” one of his classmates recalled.

As captain of his team, Hobby, as he was known in his college days, was admired for his consideration of his teammates. One sophomore on Hobby’s team recalls that, because of Hobby’s thoughtfulness, he was the only substitute to earn his “P” in the final game of the season. Hobby had put the sophomore in against the Yale team simply because he knew the neophyte player would thereby win his letter.

A lifelong friend remembers Hobby’s generosity. During their Princeton days, he and Greene lived in a rooming house with four other students. ”Greene would lend me five dollars anytime, but he would force me to go down to the drugstore to buy a ten-cent toothpaste, because it was my turn.” Years later, Orland Greene paid for that friend’s two-week trip to Bermuda with his family, waving away any talk of repayment or even gratitude. “If he liked you, the sky was the limit,” the friend said.

It seemed to his fellow students that Hobby was one of those students who get good grades without working particularly hard. He graduated in 1915 with a bachelor of letters degree and a fine academic record. After graduation, he returned to Cincinnati and went to work for Procter & Gamble, a prospering soap manufacturer that had expanded into the food industry.

Two years later, the United States entered World War I. On May 10, 1917, a month after America declared war against Germany, Orland enlisted in the Field Artillery. In September of that year, Lt. Orland Greene was sent to France to join the American Expeditionary Force under Gen. John J. Pershing. During the months that followed, Greene’s outfit was involved in some of the heaviest fighting of the war.

He was at the battle of Chemin des Dames, a strategic road held by the Germans until the Allies dislodged them. He also fought in the Toul Sector. In May 1918, he and other troops were rushed to Chateau-Thierry to stem a new German offensive in what was the first major battle involving American fighting men. In September of the same year, Orlando fought at Saint-Mihiel, which was recovered by American troops in one of the most important American actions of the war. Orland’s outfit returned to the United States in April 1919. He held the rank of captain at the time of his discharge.

Orland—he dropped his nickname, Hobby, after college—was 25 when he returned to civilian life. The next year, he married Marion McLeod Thompson. For the next decade, he used his business ability in several enterprises. At one time, he was treasurer of a leather company in Cincinnati. Later, he helped organize the Message Exchange, a service that operated in Grand Central and Pennsylvania Terminals in New York. In 1925, he listed his occupational field as estate management in Cincinnati. In 1928, he was working as a stockbroker. But Orland Greene eventually discovered that his real talent lay in handling his own investments. He displayed the same casual attitude toward finance that had marked his approach to academic life, and he achieved the same success.

In the late 1930s, Orland and his wife moved to the East. For some years, the Greenes, who were childless, spent their summers in Princeton, New Jersey, and their winters in Bermuda. But the marriage did not remain a happy one, and in 1947 they divorced.

Soon after, he met—or met again—Frances Schoen Park, the little sister of William Schoen, a fellow Princetonian. “Binky,” as she was known, was only a child when her older brother Bill went to college and returned home to talk about his friend Hobby. But Binky was an attractive widow 11 years Orland’s junior when they renewed their acquaintance at a chance meeting in Bermuda. Frances Schoen was the daughter of a steel manufacturer in Pittsburgh. As a young woman, she had married a prosperous industrialist, and she had now been a widow for some years. Binky and Orland soon decided to marry.

Friends recall the Greenes as a devoted couple, much alike in personality and interests. Although they made their home in an oceanfront house in Palm Beach, Florida, the local society was not to their taste. They had a few old friends they were loyal to, but when the high social season got under way each year, they fled to other places—a house on eastern Long Island or their hideaway in Barbados. Both loved outdoor sports such as golf and fishing, and, while Frances Greene had a special fondness for horses, Orland enjoyed a good game of tennis.

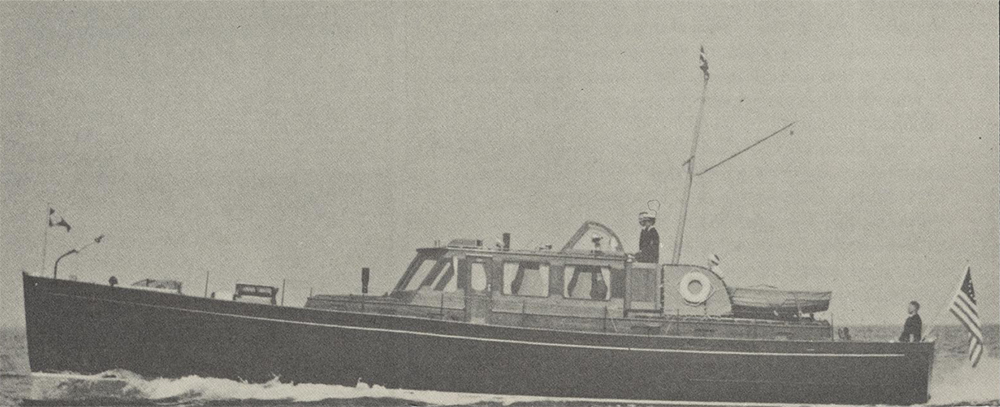

But most of all, they loved the sea. And they shared their boating life with others. In 1953, they gave “Bink I” to the U.S. Air Force “for recreational use by military personnel stationed at Palm Beach International Airport.” That boat was followed by a surplus World War II PT boat, which Orland converted into a first-class yacht and christened “Bink II.” Eventually, he gave that boat away, too, to the marine study department at the University of Miami.

Orland Greene’s generosity and deep concern for others did not end with his death from cancer on December 14, 1961, after a long illness. Many of the bequests in his will were designated for old friends, some of whom dated back to college days. In addition to a deep loyalty to close companions, Orland had great compassion for all who needed help. In his will, he established the Orland S. and Frances S. Greene Fund, demonstrating his thoughtful concern not only for dear friends, but for strangers as well.