A coal fortune dedicated to sustaining the environment.

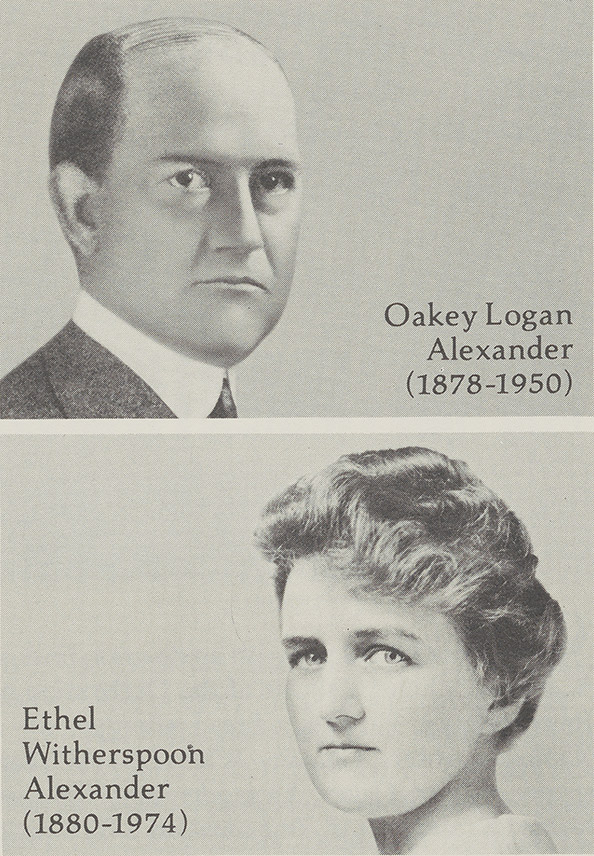

Oakey Logan Alexander (1878-1950)

Ethel Witherspoon Alexander (1880-1974)

She had an aristocratic lineage that included a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was a bread salesman for a wholesale grocery company. When Ethel Witherspoon married Oakey Alexander in 1909, they formed a team that, in time, amassed a fortune in the bituminous coal industry and later gave generous amounts of it away.

She had an aristocratic lineage that included a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was a bread salesman for a wholesale grocery company. When Ethel Witherspoon married Oakey Alexander in 1909, they formed a team that, in time, amassed a fortune in the bituminous coal industry and later gave generous amounts of it away.

Ethel Witherspoon was born on April 28, 1880, at “Glenartney,” the 350-acre Witherspoon estate and farm in Versailles, Kentucky. Her great-uncle, John Witherspoon, a Presbyterian clergyman and president of the College of New Jersey from 1768 to 1794 (renamed Princeton University a century later), did not believe in mixing religion and politics. Nevertheless, he served as a delegate from New Jersey to the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence. Ethel’s father was a famous preacher, but the other men in the Witherspoon family leaned toward finance. At one time, five of her uncles were presidents of five different local banks.

On her mother’s side, Ethel was a Viley, whose roots originated in France and whose ancestor had emigrated from Maryland to Kentucky in the late 1700s. The family had been prominent in politics and in breeding thoroughbred racehorses in Kentucky, particularly Woodford County, for a century. Ethel graduated from Hollins College, then known as Hollins Institute, in Roanoke, Virginia.

In 1909, she married Oakey Logan Alexander. He was 31; she was 29.

Oakey Alexander was born in Parkersburg, West Virginia, in 1878, the son of William and Isabella Mann Alexander, whose family came from Greenbrier County to the east. He was educated at Concord College in Athens, West Virginia. Although he did sell bakery products for a time, Oakey decided to change that when he met Ethel Witherspoon. He thought she was too beautiful to marry a man who sold bread for a living. After their wedding, he went to work for the Pocahontas Fuel Co., a large producer of high-quality bituminous coal in the southern part of West Virginia, on the border with Virginia.

An early conglomerate, the company owned not only the coal mines but also the services that transported the coal to consumers. Oakey’s primary customers were the textile and pulp paper industries of New England. In 1910, he became district manager of plants in New Bedford, Salem, and Boston, Massachusetts, and in Portland, Maine. The young couple moved to Boston.

In the next eight years, Oakey rose rapidly through his company’s ranks. By 1918, the Pocahontas Steamship Co. had been developed, and the barges and sailboats that had hauled coal from Hampton Roads, Virginia, to New England were replaced by oceangoing colliers that also transported coal to Europe and South America. That same year, Oakey was promoted to vice president and transferred to New York.

Unlike most women of her time, Ethel Witherspoon Alexander was not content to be the woman behind the man; she was the woman beside the man, collaborating with him on the design of coal terminals and colliers and taking a keen interest in the operation and maintenance of coal properties, terminals, and ships. The Pocahontas Steamship Co. was of special concern to her. Besides her sharp business head, Ethel had another advantage. She was an aristocrat, with the papers to prove it, and her membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution and similar organizations proved advantageous during those early New England years in dealing with socially prominent people and social and business organizations.

By 1929, the company had eight oceangoing colliers with an annual capacity of 2.5 million tons of coal. But 1929 also marked the beginning of the Great Depression and, like other large companies, Pocahontas had its share of problems. Oakey Alexander was more than equal to the challenge. Made president of Pocahontas Fuel in 1932, the depth of the Depression, Oakey (undoubtedly with Ethel’s help) pulled the company through that difficult time, a feat that brought him even closer to the West Virginia families who were major owners of the company. Pocahontas companies included Pocahontas Fuel Co., Pocahontas Steamship Co., Pocahontas Coal Corp., Pocahontas Light and Water Co., and Pocahontas Corp.. In addition to being president and director of these firms, Oakey Alexander was a director of the Irving Trust Co. in New York and of the First National Bank of Bluefield, West Virginia. He also was president of the Pocahontas Coal Operators Association and a director of the National Coal Association and the Bituminous Coal Institute. At one time, his directorships totaled 15.

Before the outbreak of World War II, Oakey had taken an active interest in the development of rayon, a synthetic fiber that had gained usage in the 1920s. Although he was still involved in the Pocahontas enterprises, he became an executive in the American Enka Corp. and later chairman of the board. Most of the owners of the corporation were Dutch, and when Holland was taken over by the Germans, the Dutch holdings were threatened because U.S. policy was to freeze assets of citizens in German-controlled countries. However, the Dutch owners had such confidence in Oakey’s honesty and business acumen that they turned everything over to him. It was even rumored that the gold bullion reserves of the Dutch government were hidden during World War II in abandoned Pocahontas mine shafts in Bluefield, West Virginia. When the war ended, he handed the greatly increased assets—and the gold—back to the grateful Dutch. The Alexanders counted many Dutch in their wide circle of friends, among them Queen Julianna, who was a frequent guest at their New York apartment before and after the war.

Oakey Alexander had a reputation as a hard worker and a loyal employer who demanded no less of himself than he did of his employees. In the 1940s, when many New York firms were cutting back to a five-day workweek, Oakey tried to ignore the trend. For a while, he was successful, but ultimately the tide was too strong. Eventually he agreed to close the Pocahontas offices on Saturdays, but he continued to work six days a week.

Although the Alexanders lived in New York City, they frequently visited Ethel’s ancestral home, “Glenartney,” during the summer, and they especially enjoyed entertaining friends at Kentucky Derby time.

The Alexanders also liked to entertain customers and friends aboard the two flagships of their fleet, both named SS Oakey L. Alexander and outfitted with state rooms for coal cruises from Norfolk, Virginia, to New England ports.

Oakey always had a special attachment to Bluefield, West Virginia, the business center of the coal mining industry. He founded the Alexander Baptist Church in Bluefield (Ethel founded a Methodist church in one of the other Pocahontas coal towns), and he and Ethel built a lodge near there in the Southern Appalachians. A close friend of Oakey’s ran a sanitarium in Bluefield, and Oakey usually checked in there when he needed hospital treatment. However, at the time of his final illness in 1950, Oakey was in New York. He entered the hospital on Jan. 9 and died on Jan. 21 at age 72. His widow was just two months short of her 70th birthday. There were no children. Ethel lived almost a quarter of a century longer, dying on July 26, 1974.

During their lifetimes, both Alexanders were unfailingly generous with their fortune. One of Oakey’s most important and interesting gifts was to a project far from home. He contributed to Admiral Richard Byrd’s second expedition to Antarctic, from 1933 to 1935, and Byrd’s vessel carried Pocahontas coal as ballast. Ten years after her husband’s death, Ethel created the Oakey L. and Ethel Witherspoon Alexander Foundation so their concern for others could continue undiminished.