After losing her voice, German opera singer came to America to teach music. Established a fund to support young people in music and forestry.

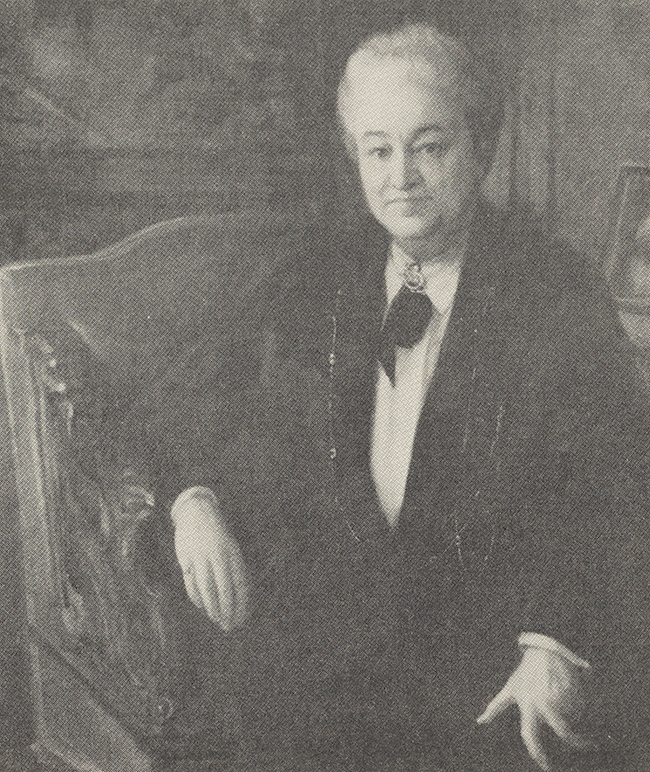

Mme. Anna E. Schoen-René (1864-1942)

During the first half of the 20th century Anna Eugénie Schoen-René was one of the most respected teachers of singing in the Western world. A former singer, Anna taught many of those who became famous in the 1920s to the1940s for opera—Karin Branzell, Thelma Votipka, Lucrezia Bori, Risë Stevens, Charles Kullman, and Paul Robeson—and on radio and Broadway—such as Lanny Ross and Jane Pickens. During this period, she not only taught her pupils impeccable musicianship but gave them encouragement that frequently involved substantial help when they needed it most. All she gave—including a scholarship fund at her death—had been hard earned, the result of overcoming personal trials. At the start of her own operatic career, she became so ill she had to give up all hope of a promising future as a singer. Anyone of lesser courage and determination might have given up completely. But neither her family background nor her driving personality could accept defeat.

The indomitable Anna Schoen-René was born in Coblenz, Germany, in 1864. Her father, Baron von Schoen, was a court councillor to the emperor and royal master of forestry and agriculture in the Rhineland. Anna Eugénie grew up in an intellectual atmosphere, strongly influenced by the works of poets and musicians the emperor had encouraged—Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Franz Schubert, Ludwig van Beethoven and Johannes Brahms. In addition, there was the French influence of her mother, from whose ancestry she later took the last part of her name, and the exuberant Italian influence of the household orderly who taught Anna folksongs, complete with dramatic gestures. “As I walked in the forests,” she reminisced, “I would sing to myself and build dream castles by the hundreds, always of future triumphs as a singer.”

A few triumphs lay ahead of her, but they were not easily attained. Her mother thought a singing career unladylike and was utterly opposed. Her father, who had raised her as a tomboy—taught by military instructors to shoot a pistol, train dogs, ride superbly and take part in boys’ sports—might have been sympathetic, but he died when she was 9. Fortunately, her brother, who became her guardian, loved music, realized she had an unusual voice, and sent her to a boarding school in Holland that specialized in music and art. The pupils used to perform for the Dutch queen, Sophie Friederike Matilda, who was German herself. The queen asked Anna to sing German songs. She did them so well that the queen helped her obtain permission to compete in the Rhenish Festivals, where a panel of musicians that included Brahms, chose potential applicants for fellowships to the Royal Academy of Music in Berlin. Anna was among those selected.

Her later skill as a teacher of Johann Sebastian Bach began at the academy, where one of her professors was the world’s leading Bach authority. While at the academy, she also joined a secret student club to study Richard Wagner, who at that time was frowned upon as revolutionary. When the Bavarian king sponsored Wagner and began the Bayreuth Festivals, young Anna would go and, in a Bayreuth restaurant, sit with Hans Richter, Anton Seidl, Siegfried Wagner and Arthur Nikisch (under whom she later coached), as they discussed Wagner’s music—an early indoctrination that was to be invaluable. Her later acclaim in Mozart operas also began at the Berlin Academy, for her voice instructor had been a student of Pauline Viardot-Garcia, a renowned interpreter of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and one of the truly great voice teachers of all time. Through her academy professor, Anna was accepted as a pupil by Viardot-Garcia, an exhilarating cultural experience of which she later wrote: “My real life as a musician and singer began only after I started my studies with her.”

Viardot-Garcia judged Anna’s voice “a soprano with mezzo color—a real Rhenish voice!” And, at her prompting, Anna began to sing opera. Her first roles were Cherubino in “Marriage of Figaro,” Zerlina in “Don Juan” and Marcelline in “Fidelio” at the Ducal Opera of Saxe-Altenburg. There followed many appearances in Germany in Mozart operas, which she sang with particular understanding. Under the patronage of Charles Gounod, who especially liked the way she sang German songs, she made her concert debut in Paris. She remained there for several years, singing in concert as well as opera, and in 1871 was selected to the Union Internationale des Sciences et des Arts. The following year she was asked to join the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Viardot-Garcia judged Anna’s voice “a soprano with mezzo color—a real Rhenish voice!” And, at her prompting, Anna began to sing opera. Her first roles were Cherubino in “Marriage of Figaro,” Zerlina in “Don Juan” and Marcelline in “Fidelio” at the Ducal Opera of Saxe-Altenburg. There followed many appearances in Germany in Mozart operas, which she sang with particular understanding. Under the patronage of Charles Gounod, who especially liked the way she sang German songs, she made her concert debut in Paris. She remained there for several years, singing in concert as well as opera, and in 1871 was selected to the Union Internationale des Sciences et des Arts. The following year she was asked to join the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

But before she could do so, severe illness struck her down. “This was a bitter blow to me,” she wrote years later, “the crumbling of all my hopes and dreams.” Yet, traits from her father came to the fore. A strong-willed man, he had insisted on self-discipline and had despised weakness of character. So, although she weighed only 98 pounds and had been given up by doctors as a hopeless consumptive, Anna was determined to start a new life as a teacher. She went to live with a sister, a teacher at the University of Minnesota, and not only recovered her health but went on to become a “musical pioneer in America.”

Shocked at what was then a lack of musical development in the United States outside New York, she started two glee clubs at the University of Minnesota, donating her services because the university had no music department. She then expanded the glee clubs into a Choral Union for the whole Midwest and began a series of May Festivals of music, where her Choral Union would augment visiting opera and oratorio companies. “I felt that the only way in which the young student could learn to discriminate between good and bad music was for him to hear the best, and the only sure way of making him love it for life was to let him take part in its production.”

She started this in 1894 and, with her connections at the Metropolitan Opera and abroad, she soon brought the era’s great musicians to Minneapolis: Nellie Melba, Marcella Sembrich and Lillian Nordica, Lilli Lehmann, Ernestine Schumann-Heink and Giuseppe Companari, Enrico Caruso, Jan Kubelik and Emma Calvé, Ignacy Jan Paderewski and Richard Strauss. In her memoirs (“America’s Musical Inheritance,” G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1941), she remembers amusing sidelights to those events—she and Companari cooking Caruso a spaghetti dinner; Nellie Melba, arriving in her private railway car, would spend her mornings practicing at Anna’s home. “I had a Great Dane,” Anna wrote, “who loved music. Melba loved animals, so the two soon became good friends. They used to romp together through the house, with her trilling and singing her cadenzas and exercises.”

Encouraged by Walter Damrosch, Anna organized a 21-person orchestra. Generally, she had to conduct it herself, reluctantly, hiding from the public behind a screen of flowers and large palms. She may have been the first women to lead an orchestra in America. At any rate, her one small orchestra ultimately became the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and the Northwestern Symphony Orchestra of St. Paul. Her fame spread, and educators sought her advice. Though not a Catholic, she supervised music in a number of Western convents and then was an adviser on singing for the Minneapolis public schools. She was appalled at what she felt were the children’s bad speaking voices and founded the first Froebel kindergarten system in the Western United States, training her teachers in proper diction and intonation. Finally, the University of Minnesota decided that Anna’s free lectures on the history of music were so significant that students should get credit for them. So, she was asked to help establish a Department of Music.

Every summer she would go back to Paris to present her best pupils to Pauline Viardot-Garcia, to continue her own studies, and to write on European musical events for an American newspaper syndicate. At Viardot-Garcia’s request, she left the United States in 1909 to become the certified representative in Berlin of the Garcia method of teaching voice. She was in Germany when World War I broke, and because she was boldly outspoken in her disapproval both of Germany’s aggression and the chaotic post-armistice revolutionary movements in Germany, she lost all her property in Berlin and nearly lost her life. Returning to the United States (she had become a citizen in 1896), she resumed teaching and, in 1925, when she was 61, was asked to join the faculty of the Juilliard Graduate School in New York.

As a teacher, she was severe, relentless, and exacting, demanding absolute obedience and discipline. She also was candid, believing that “every conscientious teacher will consider it his duty to give each student a perfectly honest judgment on his chances of making a successful career… I always feel sorry for those pupils trained by weak-kneed teachers who have pampered and catered to them. What a shock such pupils get when they encounter their first great musical director!” Risë Stevens attests to the soundness of these views. She wrote that the best advice she ever received was from Anna Schoen-René. When Risë Stevens tried for the Metropolitan Auditions of the Air, she lost. Instead of commiserating with her, Anna Schoen-René calmly spoke of the work that lay ahead and said: “My dear, have the courage to face your faults.”

Anna believed strongly that all major U.S. cities should have civic and stock opera houses where young artists could be carefully trained, and she felt there should be a national foundation of musical education to administer all scholarships, grant traveling fellowships, and protect young musicians from unscrupulous managers. At her death in 1942, she left a fund to be administered by The New York Community Trust to help young people in two dissimilar—yet, for her, understandably compatible—fields: music and forestry. Because of her love for her father and the Rhenish forests, the forestry grants might have gone to German students, but Anna Schoen-René so hated the Hitler regime and so appreciated the United States that she requested they go to American graduate or advanced students of forestry “to continue their scientific and practical research in forestation and the conservation of natural resources and control of water courses through forestry…”

The music fund’s primary purpose was to aid young Americans who “have won recognition as vocalists of promise and who have established a good reputation for personal integrity, to continue their advanced musical education.”

Characteristically, she hoped that once they had made a name for themselves, they would return the money they had been given, so other students could benefit.