Student creates fund to remember giant in world of dance.

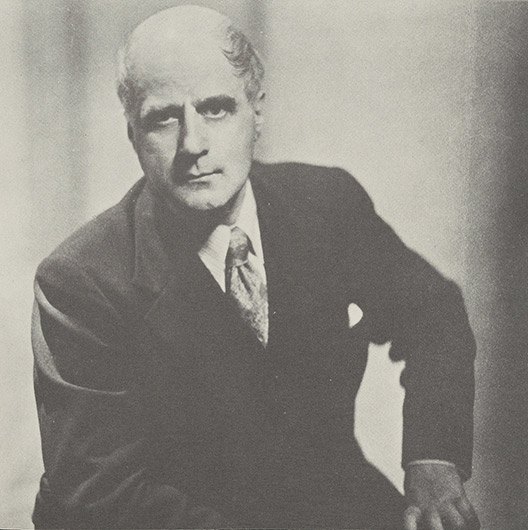

Michel Fokine (1880-1942)

Fund established by Orest Sergievsky.

Michel Fokine, known to many as “the father of modern ballet,” set his course early against the winds and tides of convention, and in his lifetime molded classical ballet into the expressive art form we know today. So great was his influence on 20th century ballet that it was said when Fokine presented his works in Paris in 1909, “The old ballet suddenly passed out of existence, and a new epoch opened.”

The First Steps

Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, on April 26, 1880, Michel Fokine was the youngest of five children of Michel and Ekaterin Kind. His father, a prosperous merchant, had little interest in the arts, but his German-born mother was an avid lover of theater and ballet, to which she exposed all her children at an early age.

When Michel was 9, his mother took him—secretly, because of his father’s objections—for an entrance audition to the Imperial School of Ballet. He was immediately accepted, and with those first steps of a small Russian boy began a new chapter in the history of ballet.

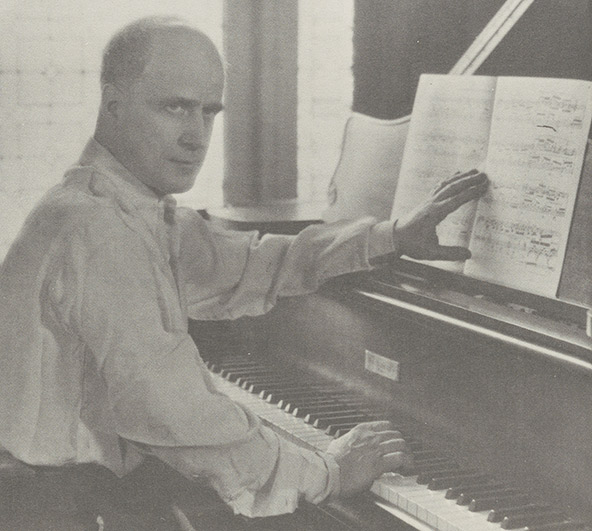

Young Michel was an excellent student and, apart from his penchant for pulling occasional pranks, worked diligently during his nine years at the Imperial School. He acquired an extensive knowledge of art and music, becoming accomplished at playing both the piano and mandolin. In dance, his training was impeccable, and his natural ability outstanding.

Disenchantment

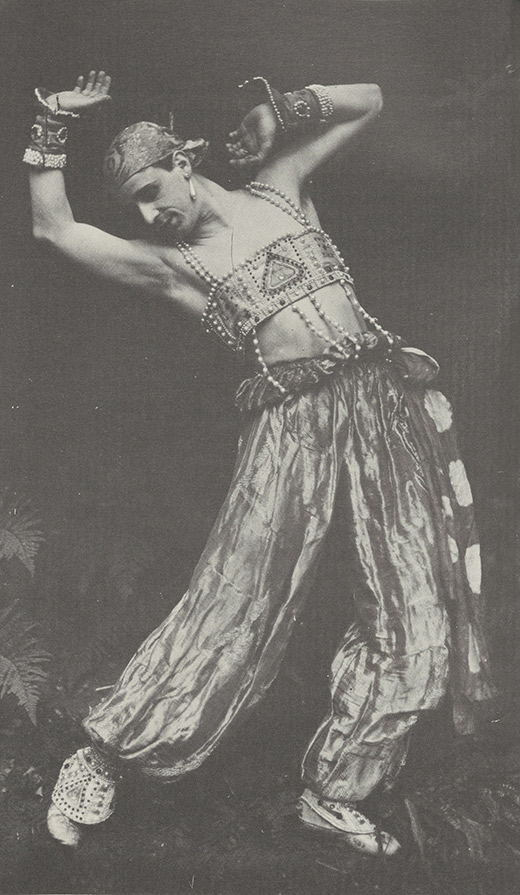

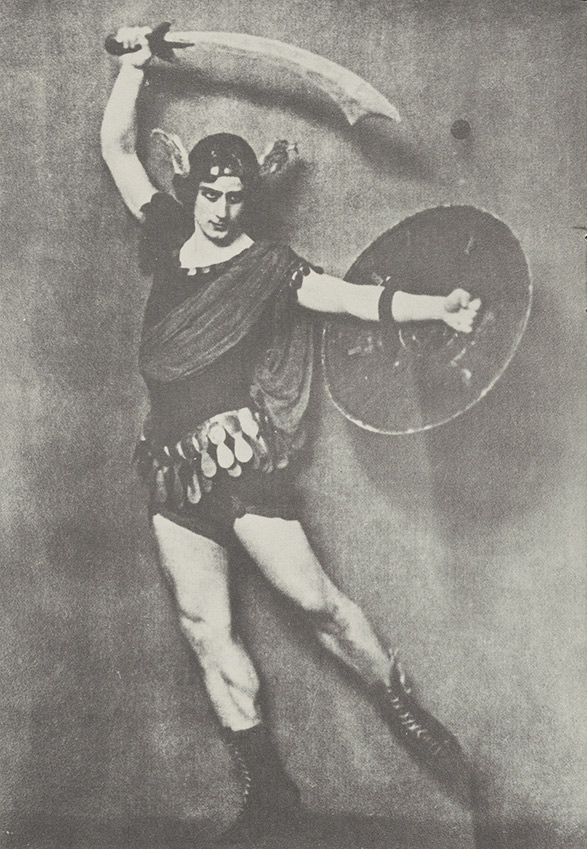

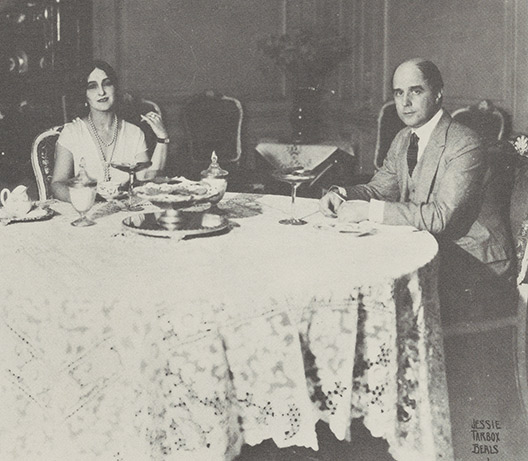

Circa 1912.

Although he could not express it at the time, Fokine later wrote that he quickly became disenchanted by much of what he was learning. He realized that classical ballet as it existed in Russia at the turn of the century had become little more than a display of acrobatic movements. To Fokine, the ballet had become so stagnant that it bordered on the absurd, constantly repeating the same trite formula—three to five acts, a spectacular pas de deux, the obligatory folk dance and mime scenes, but always the emphasis was on the technique of the ballerina. Music, steps, and decor were unrelated. Overall, Fokine felt, the Russian ballet was not fulfilling its potential as an art form.

“The dancer did not change his dance and manner to create the image of a certain period … all periods, all styles, all characters were subordinated to the dance,” he wrote. “Everything was sacrificed for one form, one style, so that the artists might display the dance, the technique.”

Fokine’s early frustrations with the rigidity of traditional ballet focused on one of his first teachers, whom he described as an excellent dancer; a gifted caricaturist; a lively, witty and talented man; a marvelous painter; and a great comedian in private life who always produced static, dull ballets.

“There was a wide gap between the gay and interesting man and his artistic activity,” Fokine wrote in his autobiography. “This gap I would describe as the result of yielding to tradition and the absence of creative initiative.”

Pavlova’s Partner

Fokine’s own time to take creative initiative did not come immediately upon his graduation from the Imperial School in 1898, when his extraordinary gifts as a dancer won him first prize and a position as a soloist in the Mariinsky Ballet. This was almost unheard of, since even the most accomplished dancers began their careers in the corps de ballet. Fokine became Anna Pavlova’s first partner, and by all accounts was worthy of such an honor. His style was said to be exceptional, his technique flawless—strong, yet graceful and expressive—and his talent for mime outstanding.

Because there were relatively few parts for soloists, Fokine danced less frequently than he would have as a member of the corps during the four years he spent at the Mariinsky. This gave him time to study many art forms and to develop his own philosophy and ideas about how he would change the ballet. He questioned all areas of the existing school of thought, even the “set, artificial smile of the dancer” and the customary applause for a well-performed combination. “Is a separate success for each individual small number in the ballet necessary?” he asked. “Do these successes not destroy the unity of the work? Is not the rule of unity, required in all other arts, just as essential to the ballet?” Fokine felt applause and taking bows in the middle of a performance fragmented and deformed the ballet as a whole, and dancers, in pursuit of applause, did not focus on their roles, but were at all times courting the audience.

Spreading a New Gospel

In 1904, Fokine became a ballet instructor at the school where he had studied. By then his ideas were clearly formed. As he described his approach to teaching, “I tried to give a meaning to the movements and poses; I tried not to make the dance resemble gymnastics. I endeavored to make the student aware of the music so he would not treat it as a mere accompaniment. I stressed the extension of the lines of the body. I lectured to my classes about beauty and aesthetics. This was a daring, unheard-of innovation; to talk about beauty during a dance class—what impudence! Everything was expected to be correct, and nothing more. But I saw, much too often, that things were correct but ugly and believed that everything should be both correct and beautiful.”

Fokine taught his students that ballet should mirror life, using the body as a means of natural expression. He saw in the human form an inherent beauty and felt its purpose was to communicate feelings rather than just look pretty or show acrobatic endurance. Fokine worked for unity in his ballet productions, believing that soloists, the corps, decor, costumes, and music should blend in harmony to express the period and theme of the ballet.

Fokine also believed that the ballet could be presented in such a way that it would appeal “not just to a handful of balletomanes, familiar with the mysteries of the ballet and conditioned in advance by the press, but to the direct, genuine feeling of the wide masses.”

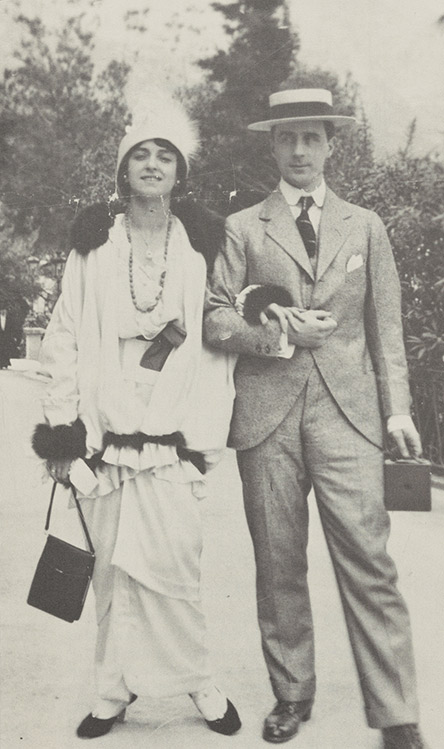

Partner for Life

In 1905, Fokine met and married a beautiful young dance student, Vera Antonova. Vera also became his dance partner for the rest of his career. Later, in writing about their close, loving partnership, he said, “Almost never had due credit been given to the tremendous influence which the collaboration of my wife, pupil and partner had on my activities as ballet master. Having studied my views and tastes, she was more exacting and demanding toward my work than I was myself. When it seemed to me I had already reached my goal, she would call my attention to the fact that such-and-such was not exactly what I had hoped as I had described the plan of the composition to her.”

Vera also played a strong, supportive role in his life, as he writes, “On numerous occasions, infuriated by acts of opposition or intrigue, by economic obstacles, or simply by a lack of understanding of my aims on the part of those who held the controlling reins in the ballet, I was ready to leave my chosen work and sever connections with the organization. At such times, the defender of my opponents was none other than my Verasha. She would absorb the impact of my initial attack and I would become reconciled to the unavoidable conditions of work and would complete the composition of the ballet.”

Reforms at Last

In the same year he married, Fokine applied his philosophy of a union of dance, music, and imagery to his first choreographed ballet, “Acis et Galatea,” and the famous solo dance, “The Dying Swan,” for Anna Pavlova. He changed ballet in every detail, from the music to the librettos, to the costumes, makeup, and stage sets. Fokine revolutionized stage dancing by allowing his dancers to turn their backs to the audience. The outdated tradition of dancers walking backwards originated in the court ballets in which they were always required to face the royalty seated in the audience. He wrote, “Now, having ceased to dance for the audience, the new ballet began to dance for itself and the surrounding people. The new approach not only enriched the dance but freed it from the ugliness inescapably connected with the necessity of walking backwards.”

Fokine also dispensed with some dancers‘ tendencies to improvise particular dances within a ballet. “A ballet,” he said, “is a complete creation and not a series of numbers. When a dancer jumps and performs feats on her toes unrelated to and unconnected with the subject of the moment, for the sole purpose of demonstrating that she is the possessor of steel toes, I fail to see the poetry in such an exhibition. When the skirt, for the purposes of displaying the legs, is shortened to the degree that it resembles an open parasol, I claim that this is unsightly, and that poetry and beauty have been sacrificed for acrobatics.”

Although his radical approach was disregarded by Czarist ballet circles and criticized by traditionalists, Fokine attracted many gifted Russian dancers, including Pavlova, Karsavina, Nijinsky, Mordkin, and Bolm.

In 1906, Fokine composed two ballets, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and “La Vigne.” These were followed in 1907 by the staging of his first ballet for the Imperial Theatre—“Le Pavillon d’Armide,” with Anna Pavlova, Nijinsky, and Fokine dancing the leading roles.

Paris—A New Era

With Fokine’s talents as a choreographer gaining renown, the impresario and ballet master Serge Diaghilev persuaded the Imperial Theatre to try the Fokine technique outside of Russia. In the summer of 1909, Fokine took his company to Paris. Among the ballets he presented that first season was “Prince Igor,” part of which includes the Polovtsian dance scene, where a band of primitive tribesmen dance before the prince. When the Paris audience saw the ensemble of male dancers whirling and jumping in wild frenzy, they were electrified, knowing they were witnessing the dawning of a new era in ballet.

The outcome of Fokine’s trip to Paris was the launching of his career as a choreographer and the beginning of the most creative, prolific period of his life. He performed in and choreographed the Ballets Russes from 1909 to 1912; at the end of that time, the company had 19 ballets in its repertory, 14 of which were created by Fokine, including “Cleopatre,” “Le Carnaval,” “Firebird,” “Le Spectre de la Rose,” and “Petrouchka.” In creating these ballets for his unique assemblage of performers, artists, writers and composers, Fokine at last realized his reforms fully.

Fokine in America

Although Fokine did not cross the Atlantic himself until 1919, his dances were first performed in the United States in 1910 by Anna Pavlova. She enthralled American audiences with her performance of Fokine’s “Dying Swan” and other compositions—so much so that the Metropolitan Opera Company planned to bring the entire Diaghilev ballet from Paris to America. But Gertrude Hoffman preceded them in the summer of 1911 by presenting unauthorized but very well executed versions of three of Fokine’s ballets—“Les Sylphides,” “Scheherazade,” and “Cleopatre”—at New York’s Winter Garden Theater.

Fokine and Vera remained in Europe and Russia throughout World War I, dancing, as “Fokine and Fokina” and choreographing until 1919, when they finally came to the United States. Fokine’s first work in America was the staging of the ballet dances in the Broadway musical “Aphrodite,” a spectacular production that opened at the Century Theater that December. The lavish musical was enthusiastically received and toured the country later that season. That same year, Fokine and Vera danced together for the first time before an American audience in a recital at the Met. Fokine soon became famous in New York as the choreographer of the Ballets Russes, his work playing to full houses. The Fokines decided to stay in the United States, setting up a home and a dance school on Riverside Drive in New York City.

From his arrival in the United States in 1919, it had been Fokine’s dream to create an all-American ballet company, and in February 1924, his dream was realized when the Fokine American Ballet made its debut at the Metropolitan Opera House.

Because of the nature of American entertainment tastes in the 1920s (vaudeville was popular, and there was a growing interest in the movies) Fokine soon realized he could not bring ballet to mass audiences by performing only in concert halls. Undaunted, he and his company toured the vaudeville and motion picture theater circuit, often appearing between comedy acts or before the featured movie. Thus, the ballet, once an art form associated with the aristocracy and European Society, became accessible to people from every stratum of life.

Despite his overwhelming success and years of acclaim for his new form of ballet, there were purists who still reproached Fokine. On September 25, 1937, The London Times called his “Le Coq d’Or,” set to the music of Rimsky-Korsakov, “a merry entertainment at which people can laugh and applaud during the music, but it can only have the most superficial likeness to the original. Caricature can be very amusing, but can these ravages be called art?” However, by making ballet exciting and accessible to all, Fokine garnered rave reviews that ultimately drowned out the critics.

An Enduring Genius

Fokine and Vera continued to perform together until 1933, packing houses wherever they appeared. In recalling his parents’ life together, their son, Vitale, describes their last performance in Toronto in 1933, when Fokine was 53 and Vera 45: “Long past their prime, they selected a program that would have taxed the energy of dancers half their age.”

Fokine remained a creative genius as he grew older. The new works he choreographed for the New York Ballet Theater in the last 10 years of his life brought critical acclaim that attests enduring gifts. The first of these was “Bluebeard,” based on the Offenbach operetta. The ballet inspired one reviewer to write: “ ‘Bluebeard’ is something to take ballet out of the caviar class and make it a bread-and-butter ‘must’ for the hoi polloi entertainment seekers. It is great fun, and it is as well the sort of theater magic that thrills balletomanes.” Another critic wrote: “Froth and comedy, frill and satire bubbling with good spirits and tingling with laughs, ‘Bluebeard’ is one long united front against the doldrums.”

In 1942, at age 62, Fokine died from pneumonia and pleurisy soon after completing his 81st ballet, “La Belle Helene,” based on the Offenbach story of Helen of Troy.

His final resting place is Hartsdale, New York. Vera, outliving him by 16 years, made weekly pilgrimages to his grave, bringing flowers and love notes. When she died just before her 70th birthday, she was placed beside him, where their legend reads in death as it did in life: Fokine-Fokina.

Sergievsky—Inspired Pupil

Such was the great ballet master’s power of inspiration that one of his pupils, Orest Sergievsky, directed in his will that the Michel Fokine Memorial Fund be established through The New York Community Trust.

Orest Sergievsky was born in Kiev in 1911 into an aristocratic Russian family. He was only 6 when the Revolution came, by which time his parents had separated, and he was left with his paternal grandmother, who raised him. The Revolution brought much hardship to the Sergievsky family. As members of Russia’s privileged aristocracy, they were now viewed as the hated “ruling class.” The family’s possessions were liquidated by the state, and Sergievsky’s father and uncles, who had been officers in the Tsar’s army, were forced into hiding. Thus, the small boy and his grandmother had to face years of hunger and humiliation alone. But Sergievsky wrote that he survived by following his grandmother’s advice: “Be above it. Walk past the ugliness . . . As long as your conscience is clear and you do not hurt anyone, you can be proud.” Inspired by his maternal aunt, a dancer of the Isadora Duncan school, and encouraged by his grandmother, Sergievsky began to study ballet at age 12.

In 1931, he and his family finally made their way to the United States, where Sergievsky realized a lifetime dream by becoming a student of the great Michel Fokine, and ultimately dancing in Fokine’s original Ballet Russe Company.

In his autobiography, Sergievsky wrote of his teacher: “Fokine expected us to do our best. He took this for granted. Repeated mistakes were reprimanded, unaesthetic line of the body was frowned upon. Not remembering a combination was almost a sin, and almost never was there a complaint from a pupil. If some step or combination was done well, we were graced with a smile that made one happy and proud.”

Sergievsky applied Fokine’s philosophy and techniques later, when he had his own ballet school and often quoted his master as saying: “Do not show the walls of the room. Show the horizon beyond. Do not stop at the ceiling but reach for the sky.”

In his autobiography, Sergievsky states, “My love of dance has been a part of me as long as I can remember myself, so long as I could dance, study, and rehearse, I was happy.” He recalls how devastated he felt when his first accident occurred: “I hit my knee on the conductor’s platform . . . I thought, I’ll never dance again! Later in life, I learned that with dancers, miracles do happen; where there is a will, there is a way; dancers break the rules of ‘never again’ many a time.”

Sergievsky directed that his fund memorialize Michel Fokine and provide for the medical expenses of needy classical ballet dancers who have suffered disabling physical injuries in pursuit of their careers.