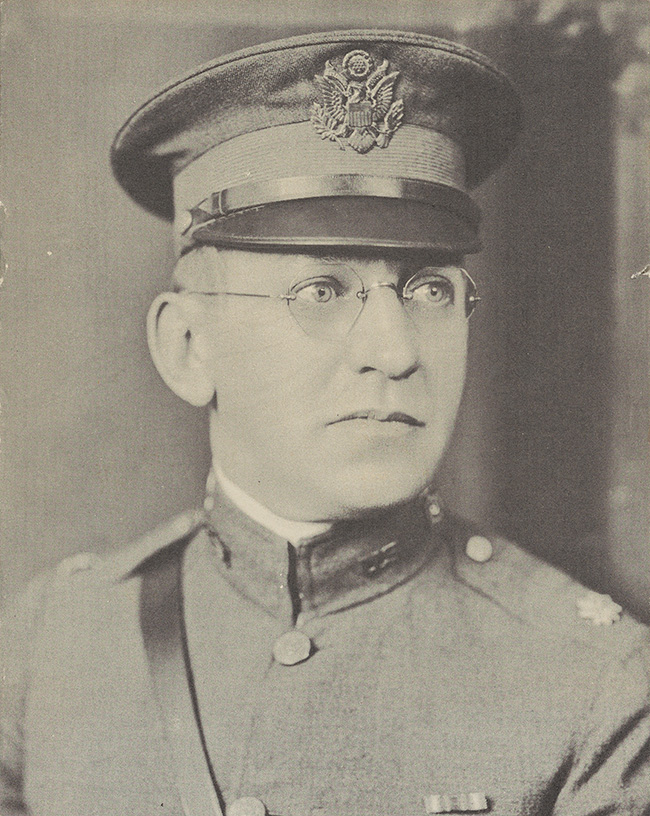

A WWI veteran, writer, and investor who gave back to the families of New York City first responders.

Manfred A. Pakas (1888-1980)

“The secret to long life,” Manfred Pakas advised a close friend on his 91st birthday, “is to keep busy. Never let things bore you.” Boredom, he said, “kills initiative. If you persevere, you will find that life is worthwhile.”

Manfred Pakas was born in New York City on June 11, 1888, to parents of Austrian and Hungarian descent. He lived nearly 92 years; fought in World War I; pursued a varied career in publishing, sales, advertising and promotion, writing, and real estate; suffered deteriorating eyesight and eventual blindness in one eye; was saddened by the deaths of two wives and his daughter; and in his last years found solace by writing inspirational poems for his friends.

Manfred grew up with his sister, Florence, on the West Side of New York, near the American Museum of Natural History. Their father, Solomon L. Pakas, a successful tailor who fashioned expensive suits for wealthy customers, invested in real estate and eventually became quite prosperous through extensive holdings that reached from Columbus Circle on Manhattan’s West Side to Riverdale in the Bronx. Their mother, Millie Brecher Pakas, was a homemaker whose love for music spurred her to contribute generously to performing arts groups.

Manfred attended New York City public schools and later attended classes at Columbia University and audited courses at Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons.

In 1908, when he was 20, Manfred went to work as an office boy with Outing Magazine. In his two years there, he rose to art editor and assistant circulation manager. In 1910, he left Outing and New York City to take a job as sales and advertising manager for Flour City Ornamental Works, an iron foundry in Minneapolis. Two years later, at age 24, Manfred returned to New York as a free-lance advertiser and promoter for a number of specialty products: Billy Burke Chocolate, Mary Garden Perfume, and Pearly White Toothpaste. The next year, he went to work as publicity manager for the New York Theatre Program Corp., integrating automobile advertising into their publications by writing an automobile column under the pen name “Veritas.”

In 1914, Manfred formed his own company to promote advertising postage stamps. Widely used in Germany, the stamps were new to America and Manfred aimed to popularize them. But the United States Post Office banned their use, with the result that today Christmas and Easter seals remain the only vestiges of ad stamps. Manfred then went to work for a company that manufactured fire engines, the American-LaFrance Fire Engine Co. in Elmira, New York. By 1917, he was handling domestic and international sales, and two of his chief clients were the United States Departments of Army and Navy. That same year, the United States entered World War I, and Manfred, 29, enlisted in the Army. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Aviation Signal Corps, rose through the ranks to major, and commanded the 431st Aero Squadron. He was injured during the war and joined the Officers’ Reserve.

In 1918, Manfred—affectionately dubbed a “lady’s man” by a friend who knew him in his later years—met and married Anna Emery, a prima-donna soprano who hailed from Portland, Maine, and whom Manfred had met when she was touring in New York in a Victor Herbert operetta.

In 1920, their daughter, Dorothy Mary, was born. Manfred returned to work for American-LaFrance, and at the same time he and Anna began investing in real estate: They bought, sold, and leased property in Florida while retaining two residences in New York—one in Pelham, the other on Riverside Drive. In 1927, Manfred left American-LaFrance so he could devote himself full-time to his real estate interests. But a hurricane in Florida devastated the Pakases’ properties there, and back in New York, Manfred, once again, ventured into something new.

He helped organize the Aviation Business Bureau, and, as head of its research department, he wrote reports and did public relations (including radio appearances) for the booming industries of aviation. At the same time, Manfred served as a public relations representative to Col. Harold Hartney, the World War I commander, and aide to General William “Billy” Mitchell.

It was during these years in New York, from 1928 to 1938, that Manfred’s eyesight—impaired during his service in the war—began to deteriorate. He became a patient of Dr. Irving Wilson Voorhees, a director of the Manhattan Eye, Ear & Throat Hospital. In 1939, Manfred’s glaucoma forced him to retire from active business. He was hospitalized and underwent several operations and then convalesced at home for three years. During most of that time, Manfred—almost completely blind—redirected his energies. He devoted himself to writing, and the subject he plunged into was nutrition. He had read and studied nutrition as a student at Columbia, but now, forced to spend his time caring for his health, he rediscovered the field with charged motivation and enthusiasm. Though his left eye was permanently blinded, sight slowly returned to his right eye, and Manfred believed—as he wrote in 1941—that nutrition was “the science that saved me.”

He wrote and published a brochure he called Food Signals, which was a sort of nutrition primer. He also wrote about the importance of daily exercise, and he lectured on fitness. A press clipping dated November 27, 1941, from The Rutherford (New Jersey) Republican and Rutherford American announced the appearance of Major Manfred Pakas at the Rutherford Women’s Club to discuss how to “Streamline Your Chassis and Improve Your Appearance.” Reported the newspaper, “One of Major Pakas’s witticisms is ‘a word to the wide is sufficient.’ ” (Manfred also practiced what he preached: He watched his diet and worked out every day, keeping his 5-foot, 10-inch frame muscular and fit through aerobic exercises.)

During this time, Anna worked as Manfred’s secretary. Together, they actively—but prudently—invested their savings. Years before, Manfred’s father, who had become wealthy through real estate investments and holdings, had transferred all his real estate to securities, and when the market crashed in 1929, all was lost. Manfred, shaken by his father’s shattered fortune, proceeded after the Depression to devote much time and care to his own investment portfolio.

While Manfred’s daughter, Dorothy, grew up, her interests turned to music and theater. Following in her mother’s footsteps, Dorothy pursued a theatrical career. She adopted her mother’s surname and, as “Dorothy Emery,” she sang and acted on stages in England and New York. In 1946, she married Harold L. Kalt Jr. at the Pakases’ home in Pelham Manor. Four years later, in 1950, Mackenzie “Kenzie” Arnold, Manfred and Anna’s only grandchild, was born. By then, Manfred and Anna had moved from Pelham back to Gramercy Park in New York City. Manfred continued writing, mostly essays and poems, and some of his inspirational and patriotic anecdotes were published in The American Mercury magazine.

In 1952, Anna died. A few years later, Manfred became reacquainted with an old friend, Violet Redler, a widow. Eventually, Manfred proposed, and they married in 1957. For the next several years, they traveled to the Caribbean, to Florida, and throughout the Midwest. In 1965, Violet died.

In 1971, more sadness colored Manfred’s life. His daughter, Dorothy, succumbed to cancer at age 51.

Manfred lived another nine years. He survived cataract surgery and an operation on his hip. He moved to a Central Park South studio apartment with a view of the park. From his window he could see the property at Columbus Circle that, years before, his father had owned. Inside his apartment, Manfred spent hours listening to his Telefunken radio, favoring the music of Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach.

Classical music was Manfred’s special love, and he attributed his attachment to the important women in his life: his wives, Anna and Violet, and his daughter, Dorothy. And Manfred read voraciously—historical biographies and psychology books were his favorites.

In his last years, weakened, Manfred continued to write. He jotted down couplets on love, truth, integrity, happiness.

“Happiness is uttering words of praise

And sharing others’ joyful days …”

And loneliness.

“Loneliness means seclusion

Bereft of any illusion

That life again be bright

Instead of long, long nights

Of loneliness.”

He sent his poems to the people who were closest and dearest to him in his last years: his physician, his investment broker, and a schoolteacher whom he had met during one of his hospital stays, a woman who reminded him of his daughter. When he died on May 28, 1980, Manfred left behind reams of essays, poems, and papers.

Manfred’s association with the American-LaFrance Fire Engine Company and his affection for children inspired him to establish in his will a special fund, administered by The New York Community Trust, to provide scholarships for the children of New York City firemen and police officers killed in the line of duty.

Manfred Pakas was a born-and-bred New Yorker. He lived and worked in the city most of his life. Through his philanthropy, the lives of other New Yorkers will be enhanced.