Audiences at the Public Theater, Lincoln Center, and other prime New York venues might be surprised to learn what they owe to a modest, poetry-loving woman from Ohio who aspired to work in a library.

Indeed, if not for LuEsther T. Mertz, there might be no New York Shakespeare Festival and much less of Broadway as we know it. She co-founded the enormously successful Publishers Clearing House in 1953 and established funds and foundations that have enriched the city and beyond for nearly 60 years.

Thanks to her generosity, The New York Community Trust invests in the arts, education, human rights, health, and other causes that keep our city vibrant and inviting.

THEATER’S “ANGEL OF THE ARTS”

“I just know a good idea when I see one.” — LuEsther Mertz

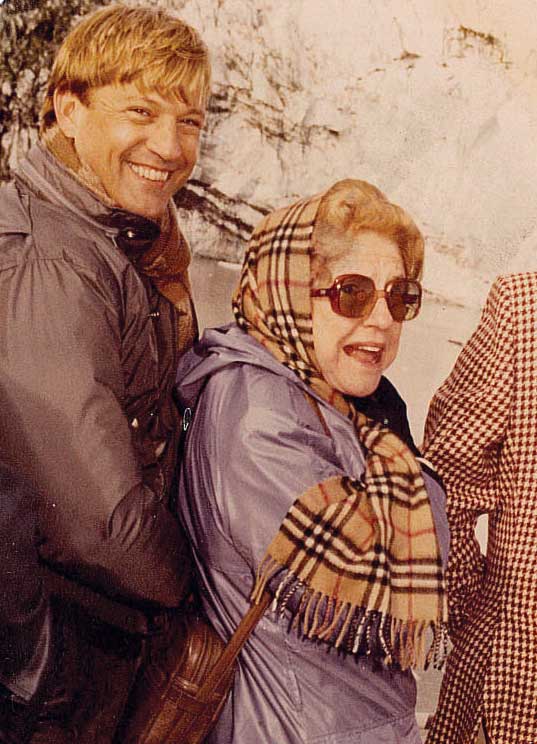

Long before she was a beloved New York arts patron or had a butterfly named for her, LuEsther Turner was the studious daughter of a Methodist minister from Rossmoyne, Ohio, who lost both of her parents when she was young. She studied at Syracuse University to be a librarian and was known for her love of poetry—she could stop in the middle of a conversation, friends recalled, and recite a complete poem appropriate to the moment.

In 1927, LuEsther married a visionary businessman, Harold E. Mertz, whom she had known since high school. They had two children, Joyce and Peter, and raised their family in Port Washington, Long Island.

Harold, a magazine publishing executive, began a sideline business with LuEsther and Joyce in 1953. Realizing that magazines needed a cheaper way to get subscription renewals than door-to-door sales, he hit on a simple but untested idea—direct mailings to sell subscriptions from many publishers at once. It started slowly. Harold, LuEsther, and Joyce sent out 10,000 letters that year and got 100 responses. “Our whole list fit into a shoe box,” LuEsther recalled in a 1986 interview.

The idea was a winner. The business outgrew their basement and became a marketing legend—Publishers Clearing House. By the late 1980s, the company represented hundreds of publishers, had more than 800 employees, and grew famous for its televised sweepstakes, which have awarded more than $100 million in prizes. LuEsther remained active in the company and sat on its executive committee until her death in 1991. (Today, the company is primarily internet-based.)

A LOVE OF GOOD READING

The family’s philanthropic nature became evident as early as 1959 with the launch of The Mertz Foundation, which supported human rights, peace movements, humane treatment of animals, and environmental protection.

LuEsther’s personal projects grew from her love of books and the arts. Aware that the visually impaired had little access to quality periodicals, she started Choice Magazine Listening, which selected articles, fiction, and poetry from periodicals and had them recorded onto vinyl records (and later onto cassettes) by trained readers. They were distributed for free.

“Do not think of this project as philanthropy,” LuEsther remarked. “To me, and those associated with me, it represents a privilege, an opportunity for communication and even self-expression. It is a chance to share some of the good reading we enjoy.”

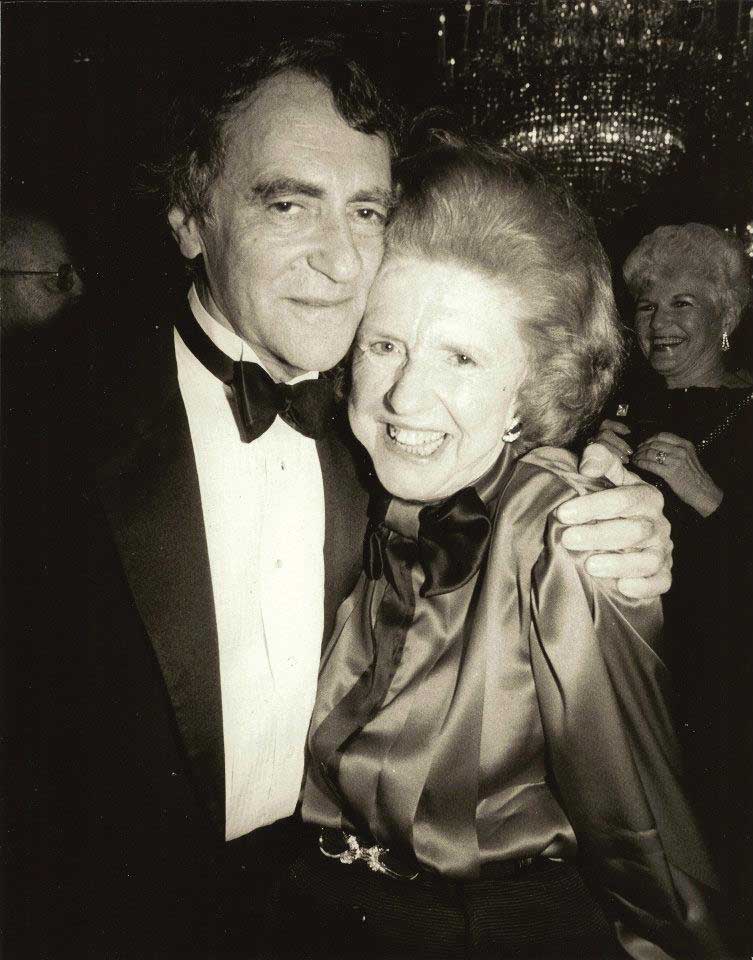

During the 1970s and ’80s, LuEsther was legendary for her support of arts and culture. A list of her board memberships and philanthropic concerns is an honor roll of New York’s cultural cornerstones, including Lincoln Center, the New York Botanical Garden, the Central Park Conservancy, and the Joyce Theater. She loved dance, contributing to the New York City Ballet and serving on the board of the Original Ballets Foundation, which supported the Feld Ballet and the New Ballet School. She was presented the Mayor’s Award for Arts and Culture in 1983, and received the New York State Governor’s Arts Award in 1986.

SAVING SHAKESPEARE

Perhaps her greatest coup as a patron was her involvement with Joseph Papp’s Public Theater and the New York Shakespeare Festival. As Helen Epstein wrote in “Joe Papp: An American Life,” LuEsther became acquainted with the Public Theater in 1971, when she attended a production with her daughter, Joyce. LuEsther adopted the Shakespeare Festival and quickly became its chief financial contributor.

In 1970, Papp was desperately seeking to bring “Two Gentlemen of Verona,” a musical adaptation of the Shakespeare play, to Broadway. He and his co-producer, Bernard Gersten, took LuEsther to lunch to explain their dilemma: If they could move “Two Gents” to Broadway, it would put the Festival “squarely in the mainstream of American Theater” and “generate the kind of income” that their hit musical “Hair” had earned. Because they had licensed “Hair” to a commercial producer, they explained, their cut of the profits was small

compared to overall revenues. A backer for “Two Gents” would ensure that the festival would own the profits.

As Epstein relates, several days later, LuEsther wrote to Papp and Gersten: “I have thought a lot about ‘Two Gents’ and what it will mean to the Shakespeare Festival. And I am more sure than ever that we should not give any part of it away to anyone else. Therefore I am prepared to say that I can and will guarantee a contribution up to the $250 million we talked about at lunch… We just simply cannot afford to miss this chance to get on easy street.”

“Two Gents” was a stunning success: It opened to rave reviews and ran for 18 profitable months. The Shakespeare Festival had become the first not-for-profit company to move a show to Broadway and retain all the rights. That paved the way for successes like the legendary “A Chorus Line,” another move to

Broadway underwritten by LuEsther. Papp and the Festival gained international stature and LuEsther became chairwoman of the festival.

NO WISH FOR THE SPOTLIGHT

Recalling LuEsther’s modest nature, Papp was quoted in The New York Times as saying that, despite her wealth, “there was nothing in her that suggested anyone was different from anyone else.” He added that she “never wanted to be in the spotlight.”

Triumph came with more than a fair share of tragedy. Harold and LuEsther’s son, Peter, died in 1954 during a fraternity initiation at Swarthmore College. The early 1970s saw the dissolution of LuEsther’s marriage to Harold, and in 1974, their daughter, Joyce, died of cancer. The Joyce Theater on Eighth Avenue at 17th Street in Manhattan is named in her memory. In 1988, LuEsther took on the chairmanship of the Joyce Mertz-Gilmore Foundation after the death of her son-in-law, Robert Gilmore. Late in life, the woman who founded a magazine for the visually impaired lost her own vision.

LuEsther was sustained by her belief in the innate goodness of people, her love of the arts, and a true enjoyment of giving. As her friend Georgia Delano remarked, “LuEsther would always say, ‘Don’t thank me because this is my pleasure.’”

She would refer to the Joyce Theater and the Feld Ballet as “her jewels,” and downplayed her philanthropy by saying, “I just know a good idea when I see one.” For all her giving, the only location recognized with her full name is the LuEsther T. Mertz Retinal Research Center at the Manhattan Eye, Ear, and Throat Hospital. At the Public Theater, the performance space dedicated to her is named simply LuEsther Hall, while the library at New York Botanical Garden also bears only her first name.

Her friend, the biologist Paul Ehrlich, immortalized her by naming a species of butterfly after her—euphydryas editha luestherae—appropriate for an “angel of the arts.”

LuEsther died in 1991. In 1995, the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust established several funds in her name at The New York Community Trust.