Creating a legacy of health for New York and her beloved home in Missouri.

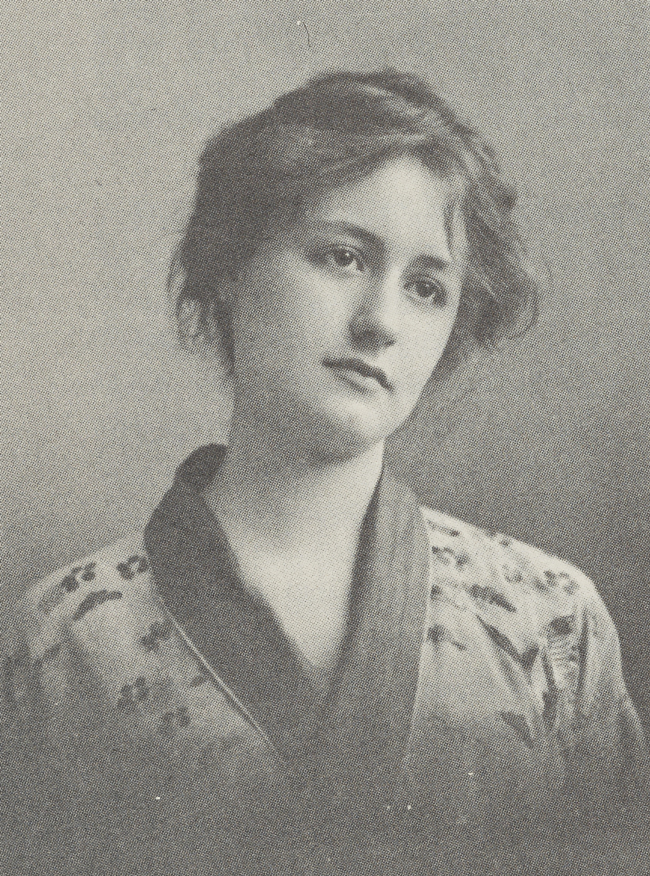

Lucy Wortham James (1880-1938)

“She has the most beautiful mind I have known since the last time I saw her.” This unusual tribute came from Sir William Osler, one of the great figures in the medical world at the turn of the century. The remarkable woman he referred to was Lucy Wortham Angus James, an American of considerable beauty and wit. Although she was one of the most delightful hostesses Washington, D.C., has known, she will be better remembered for her interests in music and medicine, ecology, and recreation—fields far removed from the whirl (and often, to her, the tedium) of capital receptions.

Because of her background, Lucy James felt keenly the responsibility of her country’s heritage. Her James ancestor was an iron master who settled in Maryland in the 1640s. In the late 1700s, his descendant, Thomas James, set out on foot for the West, where he sold iron kettles and other housewares to settlers of the Northwest Territory. One day he met a traveling band of Shawnee Indians and, noticing on their faces a red paint he suspected was made from hematite, one of the most important iron ores, he asked them to lead him to its source. After a long journey, they arrived at a beautiful spring they called Maramec, near a swift river and a rich iron deposit in the Ozark foothills. He bought the forested tract from the government in 1826 and founded an iron works. It made his family prosperous by providing much of the iron used by the pioneers who opened up the Midwest. During the California Gold Rush, James iron rolled west on the wheels of prospectors’ wagons, and during the Civil War, it sheathed Union gunboats patrolling the Mississippi.

A few miles from the ironworks, Thomas’ son, William—known as “The Iron King of Missouri”— established the town of St. James, Missouri. There, in 1880, his granddaughter Lucy Wortham James was born. Lucy’s childhood was spent in Dakota and Sioux Indian country, then in St. James and Kansas City and in El Paso, Texas. When Lucy was 14, her mother died of tuberculosis, and her great-uncle, Robert Graham Dun, asked her to come live with him in New York. Just as her grandfather had been a pioneer in industry, so her great-uncle was a pioneer in finance: He founded what was to become the multiple service agency of Dun & Bradstreet Inc.

He also was a cultivated man of the world who sent Lucy to the Spence School and introduced her to the arts. What inspired her most was music. Hoping to become a concert pianist, she went to Vienna to study under Theodor Leschetizky, who had taught famed pianist (and former Polish prime minister) Ignacy Jan Paderewski. But under the stress of the arduous hours of practice, she, too, contracted tuberculosis. When she recuperated, Leschetizky told her that her health would never permit a professional career. “Then I shall give it up completely,” she said. She never played again.

Soon Lucy and her father visited Japan, where a Dun cousin, who had been minister to Japan was living. There she met Huntington Wilson, who was United States chargé d’affaires, and shortly afterward, in 1904, they were married. It proved to be an unhappy marriage (after 10 years they were divorced, and Lucy resumed her maiden name), but Lucy’s strong sense of duty made her determined to help her ambitious young husband in his diplomatic career. This she did masterfully. Lucy’s charm captivated those whom the chargé d’affaires had to entertain, and it impressed diplomats and politicians who could be helpful. Such a man was William Howard Taft, later president but then United States secretary of war, who introduced her to Secretary of State Elihu Root. She seized the opportunity to ask for a promotion for her husband. He got it. Thereafter, whenever Elihu Root met the couple, he smiled at Lucy and asked, “How’s the firm?”

Outwardly, the life of “the firm” was fascinating. During the Russo-Japanese War, the Wilsons lived in Japan, where Lucy worked with the Japanese Red Cross and made many lifelong friends. Among them were Yukio Ozaki, a founder of the anti-militarist Progressive Party of Japan; American war correspondents Jack London, Richard Harding Davis, and Willard Straight; and Capt. (later General) John Pershing. Later came diplomatic travels to China, the Philippines, Turkey (immediately after the Young Turks’ revolution), the Balkans (just before World War I), and the Andean countries of South America. When Philander Knox became secretary of state, he appointed Huntington Wilson his undersecretary. Since he disliked formal dinners, Knox left much State Department entertaining to the Wilsons. Lucy’s dinners became famous. Her Japanese cook provided superb meals, and Lucy proved to be one of the most gracious hostesses in the capital’s history.

After her divorce in 1915, Lucy led a quieter, more intellectual life. She maintained a delightful New York apartment, spent many springtimes in St. James, and summered in Newport, Rhode Island, in a secluded seaside house she had largely designed herself. But she shunned ostentatious parties. Of one such, she said, “All the men could talk about was the stock market and their health.” She preferred more stimulating groups—the Schola Cantorum, the Friends of Music, and the literary salon of Frances Wolcott, which was a meeting place for leading artists, actors, writers, and musicians of the period. Lucy’s interests were surprisingly varied: She was a charter member of the Theatre Guild; she was a critical student of poetry; she founded a model dairy farm; she was an influential member of the board of directors of Greenwich House and Memorial Hospital in New York. Having inherited part of the fortune of R.G. Dun, she was able to combine philanthropy with her other interests. When the firm later became Dun & Bradstreet Inc., she was its largest single stockholder.

Believing that in the Heartland of America lay the pioneer qualities that made this country and that must be preserved, she practiced her philanthropies in the counties around St. James. She left money to establish the James Memorial Library. She felt that children should learn to love books, and she once remarked that she would be quite satisfied “if but one genius received his inspiration from his early reading in this library.” Though she was childless, she adored children. She was most concerned with building character in the young and with stimulating their creativity. No one will ever know how many talented young musicians and writers she helped toward a higher education, for she gave so tactfully that even the students’ neighbors did not know.

She also was ahead of her time in her gifts to science, becoming interested in the genetics of mental illness and in psychosomatic medicine long before those fields became scientifically popular. Understanding the importance of basic research, she contributed the money to build the Johns Hopkins Woman’s Clinic to emphasize research in gynecology, and she financed the first research budget and the first experimental animal quarters for the laboratories of Memorial Hospital in New York.

A prominent lawyer once said that Lucy James had a remarkably discriminating and astute legal mind. Another friend recalls that “Mrs. James was a wistful person and essentially sad, but she was one of the funniest people I’ve ever met, a superb mimic, a great conversationalist with a keen sense of the ridiculous.” Of her magnetic personality, several acquaintances remember that “one was unaware of others when she was in a room.” Yet at heart she was very shy, modest, and retiring.

Tragically, she was plagued most of her life by illness that often was painfully debilitating. Reflecting on her death at the age of 57, a friend summarized: “Lucy James had too fine a mind for her bodily strength.” Perhaps the most revealing indication of her inventiveness and imagination came in her own comments on her philanthropies. She said she wanted them to be kept “flexible in response to the times … I do not want to make any rigid requests because circumstances may completely change the ideas which I hold at present.” It was to achieve such flexibility that she established her memorial in The New York Community Trust.