Honoring the legacy of an exemplary lawyer, prosecutor, and judge who dedicated funds for law scholarships.

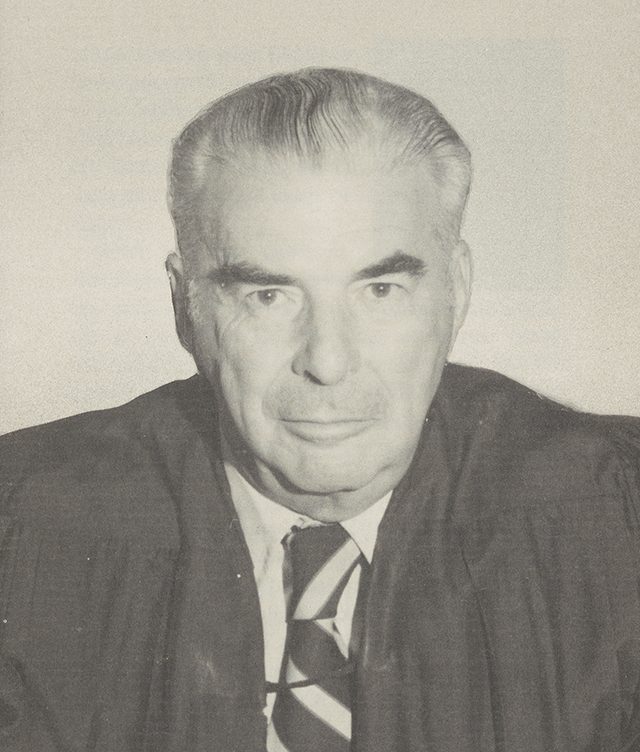

Lloyd F. MacMahon (1912-1989)

It’s the winter of 1953-54, and on the front pages of the newspapers, next to stories on the hydrogen bomb and Senator Joe McCarthy, is the well-known figure of mobster Frank Costello.

The Mafia’s “boss of bosses,” a sophisticated racketeer, hoarse-voiced public figure and friend to many a New York politician was about to be prosecuted on charges of income tax evasion. Costello seemed unworried. Unlike Al Capone, who had never paid any taxes, Costello had paid more than $500,000 in taxes over the years. He had filed returns showing substantial “miscellaneous” income, and he figured that was good enough to cover him.

Standing between Costello and acquittal was Lloyd F. MacMahon, recently appointed chief assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York. The previous administration convicted Costello of contempt of Sen. Estes Kefauver’s committee and obtained the tax-evasion indictment but concluded the grand jury proceedings without obtaining much evidence. MacMahon’s team had to prepare the case almost from scratch. To prove that Costello had obtained more income than he declared, the government would have to accumulate hundreds of details and get testimony from his friends and associates.

But MacMahon was no stranger to hard work. Born into a working-class family in upstate New York, he had supported himself through college and law school in the depths of the Great Depression. He had put in long hours as a trial lawyer in a prominent Manhattan law firm. Preparing for the Costello case, he worked deep into each night in his office overlooking Foley Square.

When the case came to trial in April 1954, MacMahon’s countless hours of preparation and strategy paid off. He proved a “net worth” case, showing that an increase in Costello’s net worth, plus annual expenditures, far exceeded his declared income. The prosecution’s case was proven with a parade of witnesses, many of whom were hostile to the prosecution but were forced to admit the facts about financial items large and small.

A Louisiana casino had paid cash profits to Costello. A New York racetrack had paid him money to ensure that bookmakers would not do business at the track. Much of the story consisted of go-betweens who had doled out cash for Costello’s expenses. Bits of evidence revealed a lavish lifestyle—daily manicures, expensive suits, an account with a florist in the name of “C. Frank,” $18,615 for a family mausoleum in another name. MacMahon also amassed circumstantial evidence that Costello’s money had not come from loans, gifts, bequests, or a prior cash hoard.

By the end of the six-week trial, MacMahon and three younger prosecutors had put into evidence hundreds of documents and the testimony of well over 100 witnesses. Costello’s attorneys called one witness, an expert accountant who had been an FBI agent; his charts and schedules were completely undermined by MacMahon’s cross-examination. MacMahon’s incisive summation took less than an hour, and the jury convicted. Later, he argued before the U.S. Court of Appeals in opposition to Costello’s appeal, and the court upheld the conviction. One indication of MacMahon’s thorough preparation was that he had outlined his appellate brief long before the trial had started.

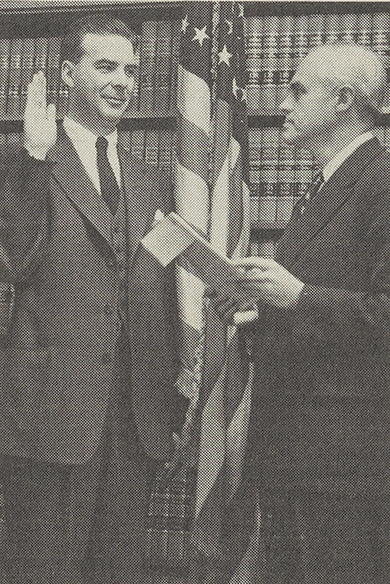

This was an early chapter in Lloyd MacMahon’s career of public service. From 1959 to 1989, he served as a federal judge. His colleagues and law clerks knew him as a jurist with a big-hearted compassion to complement his toughness and intellect, and as a mentor who taught dozens of young lawyers how to be trial lawyers. He also was a devoted husband and family man.

Elmira and beyond

The values that contributed to his professional success and personal happiness were forged in a small-town childhood spent in New York’s Finger Lakes region. Lloyd was born in 1912 to Frank and Edith MacMahon of Elmira, New York. His father was a tool-and-die maker at a Remington Rand factory, and his mother managed the household. Love and guidance were in abundance in his childhood, as well as a strong belief in work ethic. A young man during the Great Depression, he worked his way through school, earning his tuition and expenses for his undergraduate education at Syracuse and Cornell Universities, as well as Cornell Law School, where he graduated in 1938.

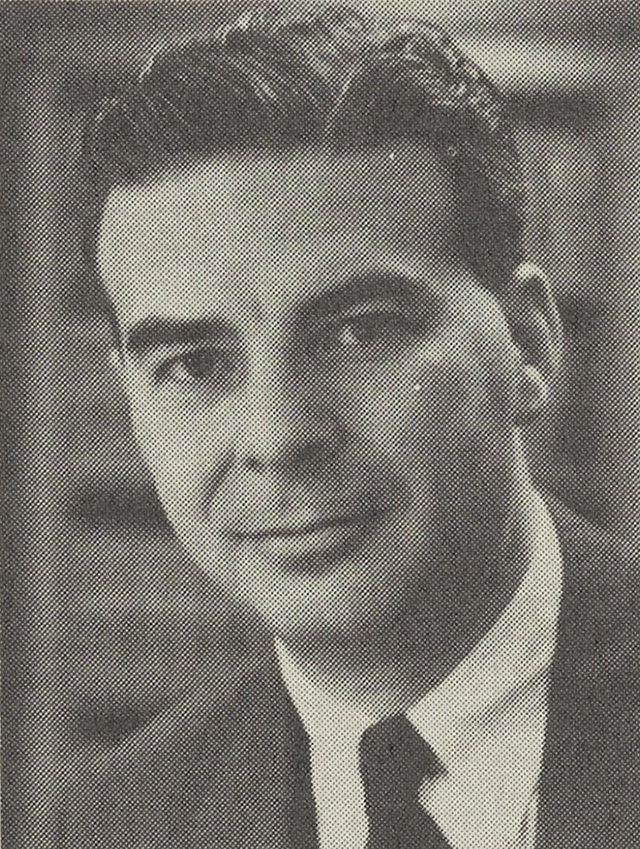

That year, MacMahon married Margaret Daly. They had been friends since they were teenagers. Elmira knew them as Peg and Mac. He settled down to life as a small-town lawyer and they started a family. For four years he enjoyed practicing in a small firm in Elmira, but then decided to look for bigger challenges.

In 1942, he headed to New York City to work for the Wall Street law firm of Donovan Leisure Newton Lumbard & Irvine. In 1944, the Navy called him away from his wife and two little daughters. He served as a lieutenant, junior grade, escorting convoys across the Atlantic.

From lawyer to federal judge

After the war, he returned to Donovan Leisure and proved his mettle as a trial lawyer. His mentor was J. Edward Lumbard, a senior partner and eminent litigator.

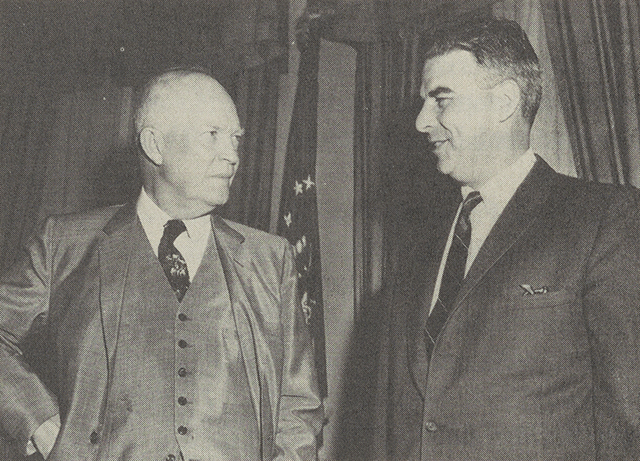

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower selected Lumbard to be the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, and Lumbard asked MacMahon to accompany him. From 1953 to 1955, MacMahon was the chief assistant U.S. attorney, helping train about 60 young assistant U.S. attorneys and personally trying three cases in addition to the Frank Costello case. Lumbard and MacMahon revitalized the U.S. attorney’s office. They were progressive in their hiring practices, appointing Miriam Goldman (later Judge Cedarbaum) when women prosecutors were virtually unheard of, and two young Black lawyers, Clyde Ferguson (later a law school dean) and Samuel Pierce (later a Cabinet officer). Lumbard and MacMahon also created the student intern program, which annually introduced dozens of law students to the work of a prosecutor’s office and became the model for many similar programs.

Lumbard was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals in 1955; MacMahon briefly replaced him as U.S. attorney but then became a name partner at the law firm of Kramer Marx Greenlee Backus & MacMahon. In 1956, he headed Citizens for Eisenhower in New York, and in 1958, he became national chairman of Citizens for Eisenhower.

In 1959, President Eisenhower named MacMahon to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, one of the oldest and largest federal courts in the nation. He served there for 30 years, including a term as chief judge from 1980 to 1982.

30 Years on the federal bench

Over the course of his career, Judge MacMahon heard hundreds of criminal and civil trials, from the merger of Manufacturers Bank and Hanover Trust to the reapportionment of New York Assembly districts. His extensive experience as a trial lawyer gave him an easy grasp of legal issues and rules of evidence.

In 1959 and 1960, he presided at two of the first criminal trials brought under the federal securities laws—U.S. v. Guterma and U.S. v. Crosby. The U.S. attorney’s office presented these cases without the assistance of the Securities and Exchange Commission. In those days, the SEC limited itself to civil proceedings, believing that securities violations were too complex to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt to a jury. Fortunately for the development of criminal securities enforcement, MacMahon had a knack for making complex subjects understandable. His instructions to those two juries remain the pattern for judges in securities fraud cases to this day. In 1962, he was assigned to U.S. v. Bentvena, et al., a notorious case that demanded the judge’s firm control and physical courage. The government was prosecuting Carmine Galante and 13 other defendants for importing heroin. Another judge had presided at the first trial, which lasted six months and ended in a mistrial after the foreman of the jury was thrown down a flight of stairs in an abandoned building and nearly killed. Judge MacMahon completed the second trial in less than three months, despite a series of delaying tactics, threats, and outbursts such as two described in the appellate court’s opinion:

“Panico climbed into the jury box, walked along the inside of the rail from one end of the box to the other, pushing the jurors in the front row and screaming vilifications at them, the judge, and the other defendants. On another occasion, while the defendant Mirra was being cross-examined by the Assistant United States Attorney, Mirra picked up the witness chair and hurled it at the Assistant. The chair narrowly missed its target but struck the jury box and shattered.”

Judge MacMahon restored order by having Panico and Mirra shackled and muffled with surgical masks. (The masks permitted them to be heard by their nearby attorneys but prevented their voices from carrying to the jurors.) The Court of Appeals approved this precedent-setting action as justified and necessary to prevent the intimidation of jurors.

In 1967, he tried a nonjury patent case, Ritter v. Rohm & Haas, involving the frontiers of organic chemistry as well as conflicting testimony about the state of French patent law during the Nazi occupation. The opposing lawyers were astonished when MacMahon completed the taking of testimony in eight days—and understood it. A legendary “quick study,” he did some homework in organic chemistry at the start of the trial, and soon he corrected a Ph.D. chemist who was diagraming a complex molecule on the court blackboard. MacMahon wrote a thorough opinion and neither side appealed.

As a legal administrator, MacMahon had a far-reaching impact on the judicial system. Chairman of the Committee to Expedite the Disposition of Cases, he was the prime mover in switching the Southern District from a master calendar system to an individual assignment system in 1971. Under the old system, a single case moved slowly down an assembly line from one judge to another; each judge heard the case at different stages. That created opportunities for delay. The individual assignment system placed the entire responsibility for each case on a single judge. This led to greater efficiency and productivity. In its first year, MacMahon’s new system resulted in a 39 percent reduction in the district’s backlog of cases.

Judge MacMahon was extremely efficient at dealing with a heavy caseload. He was, in the words of a former clerk, “always on top of the situation, always ready to hear a case, and always ready to move a case along.” He worked hard to avoid wasting jurors’ time and to avoid having the justice system become too slow and expensive for ordinary people.

When he became chief judge of the Southern District in 1980, he strove to increase the collegial spirit of the court, which by then consisted of 26 judges plus senior judges. He established a committee system that, for the first time, allowed each of the 26 judges to participate in some aspect of the administration of the court.

The family man

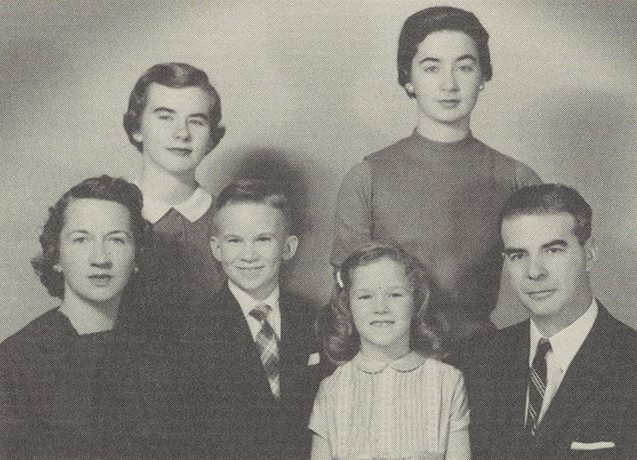

The private MacMahon was warm and unpretentious. He and Peg lived in the same house in White Plains for almost 40 years. They had four children, Patricia, Kathleen, John, and Theresa.

He was first and foremost a family man, preferring a weekend barbecue with family and friends to elaborate social engagements. The MacMahon children remember a father who worked hard but also was available for skating on winter nights or swimming at Jones Beach. Each of the children recalls a sense of care and individual attention that he later extended to his 12 grandchildren.

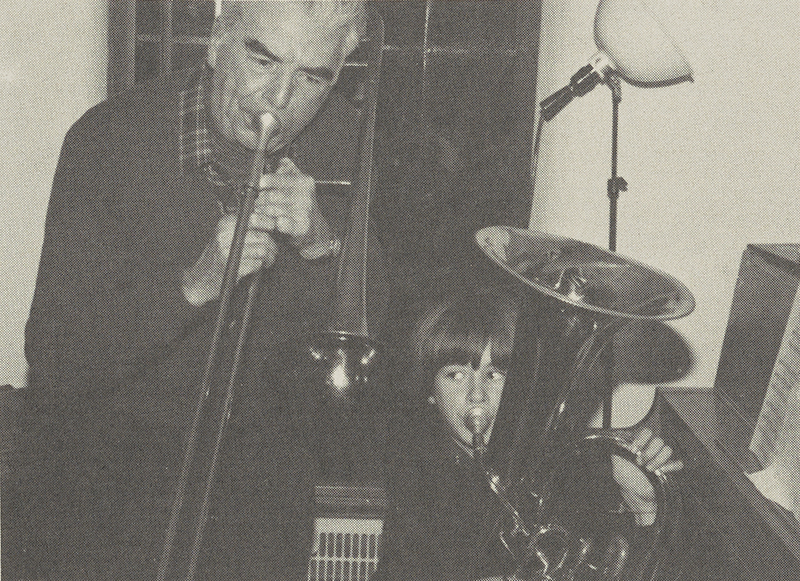

He was a man of wide interests, many of them self-taught. He played the piano by ear, painted landscapes, carved wood miniatures (once whittling a nativity scene), taught himself German, studied astronomy, shot pool, played poker, and golfed. He grew vegetables in square-foot plots and was an early environmentalist and recycler. On a family bet, he taught himself how to sew and made a shirt from scratch. (This experience came in handy during a civil case in which a famous fashion designer was on the witness stand; Judge MacMahon’s comments showed he was acquainted with the finer points of stitching.)

A devout Catholic, he often attended the daily Mass at St. Andrew’s, the church at the south side of the courthouse. After his death, the church placed a plaque in his memory at the foot of the outdoor statue of St. Andrew.

Mentor to young lawyers

MacMahon’s passion for the law as a profession was most directly expressed in his relationship with his law clerks. This professional family was increased each year with two new law clerks, fresh out of law school. At his death, there were almost 60 of them, ranging in age from their 20s to their 50s. He said they kept him young, and he relished their diversity. Many became trial lawyers, but one was a university president and another became an avocado farmer.

Douglas Eaton, a former law clerk, remembered MacMahon was different from many other judges: “He was extremely paternal and generous with his time, taking the trouble to explain trial lawyering to complete novices. His clerks spent less time in the library and saw more trials than other clerks got to see.”

His law clerks never considered their term over; they knew he was a friend and always available for advice. Regardless of the paths they followed, they returned to his chambers to visit him and Millie Babino, his secretary for 36 years.

MacMahon received two nationwide assignments: the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and the Committee on Judicial Ethics. For many years, he heard extra cases in the Northern and Western Districts of New York, a duty that took him back to the upstate country he knew and loved. Just after returning from a Northern District case, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in White Plains on April 8, 1989, at age 76. He had given almost half his life to public service.

Lloyd MacMahon Fellowship Grants

In his memory, his law clerks and numerous other lawyers and law firms contributed more than $200,000 to establish the Lloyd MacMahon Fellowship Fund, a permanent endowment. The income is used to benefit the summer intern program at the U.S. attorney’s office for the Southern District—the program created by Lumbard and MacMahon in 1953.

Since 1989, students have been able to apply for Lloyd MacMahon Fellowships, for the benefit of one or more law students who will spend the summer after their first or second year of law school (or the equivalent point in their law school career) at the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York.

The judge would undoubtedly be pleased that this fund enables talented young people to get valuable training by working for that renowned office. If they follow Lloyd MacMahon’s example, the dividends to the community will multiply in abundance.