Actress married to early motion picture director D.W. Griffith.

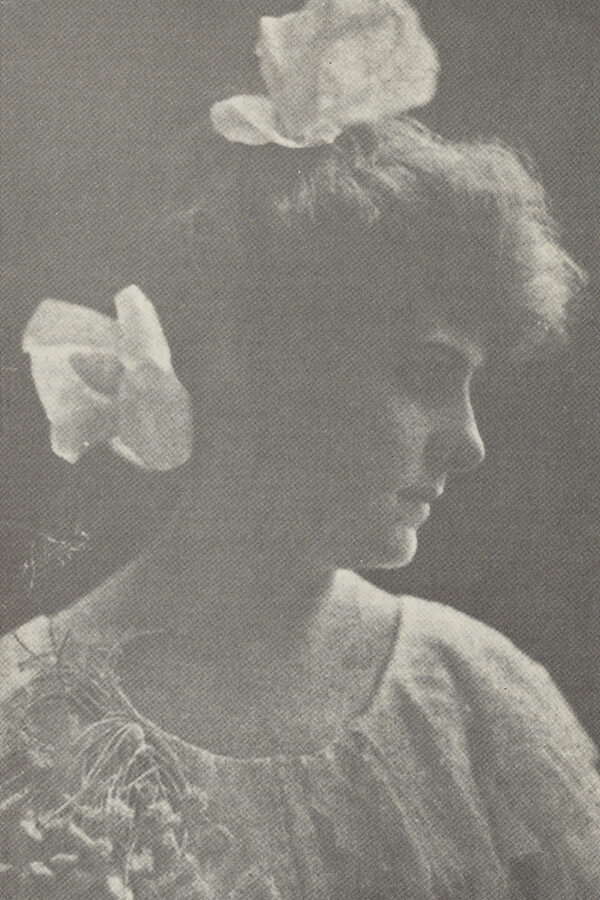

Linda Arvidson Griffith (1886-1949)

In the summer of 1905, Linda Arvidson, a beautiful young actress struggling for recognition and eager for work, picked her way through San Francisco’s decaying Mission Street area. Her destination was the Grand Opera House, where a local company was casting for a series of dramas. Once the sparkling ornament of an elegant neighborhood, the Grand Opera House had faded to a tarnished but still romantic relic of a bygone era. To reach it, Linda passed second-hand stores, pawn shops, cheap restaurants, and dismal saloons. But the surroundings did not bother her, for she knew that at the Grand Opera House, Shakespearean repertory companies occasionally played, a grand opera company headed by Enrico Caruso sometimes performed, and small stock companies put in brief appearances between such illustrious attractions.

Luck was with her that day. Linda, who was 19, was hired for the role of a boy servant in a play called “Fedora.” In her only scene, a civil officer sat on a high stool behind a large desk. As the servant entered the room and timidly approached the desk, the officer boomed, “At what hour did your master leave Blu Bla?” The startled servant stammered a reply and fled.

Later, the “servant” learned that the booming voice belonged to an actor named Griffith. He introduced himself as Lawrence Griffith, but later the tall, sharp-featured actor confided that he would use his given name—David—only when he had achieved success. Although he was 30 years old, he did not yet know whether fame would come to him as an actor, stage director, grand opera star, poet, playwright, or novelist, so diverse were his talents. A number of years went by before he announced to the world that his real name was David W. Griffith. By then, his fame was secured—not through any of the talents he had earlier shown, but as a director of motion pictures.

The two aspiring actors had come from very different backgrounds before their paths crossed on the stage of the Grand Opera House. David Wark Griffith was born in LaGrange, Kentucky, on January 22, 1875, the son of Col. Jacob Wark Griffith, who fought under Stonewall Jackson in the Civil War. Called “Roaring Jake,” because of his thundering voice, the elder Griffith loved Shakespeare and imparted his love of drama and literature to his only son. At age 16, David went to work at the local newspaper. Soon afterward, he became a correspondent for the Louisville Courier-Journal. But after he saw a performance by a visiting stock company, David made up his mind to become an actor. Eventually, he managed to get a small role and later other minor parts, but the pay was always so low that he was forced to work as an elevator boy and later as a clerk and book salesman to support himself.

Finally, David Griffith joined a traveling stock company. The play he was in, “Miss Petticoats,” got as far as San Francisco before it was stranded—no more engagements and not enough money to get back home. With others of his unemployed company, David made his way to the Grand Opera House, where he got the part as the civil officer. In one scene, there appeared a servant boy played by a girl with astonishingly beautiful blue eyes. (“You could get parts in New York just on your eyes,” he told her later.) She seemed so frightened the first time he shouted his lines at her that he made it a point to find her after the rehearsal and introduce himself.

Linda Arvidson, the girl with the beautiful eyes, was the daughter of a “Norseman,” as she referred to her Scandinavian father, who had settled on one of San Francisco’s hills in the wind and fog that reminded him of his homeland. She lived with her parents and sister, who, although they knew of her desire to be an actress, had never been told about her first job on stage in the summer of 1904. As one of a group of fishermaids making merry in a village square, Linda Arvidson earned $3.50 a week.

The fishermaid caught the director’s eye, and soon Linda was picked for an ingenue role at Ye Liberty Theatre in Oakland, California. With this experience in hand, Linda began calling on managers of road companies that came from the East and were always in need of “maids,” “special guests at the ball,” and “spectators at the races.” New York was the goal, but for a young actress without money for a railroad ticket, the only way to get there was to join a road company going in that direction.

Discouraged with such small beginnings, Linda and a similarly ambitious friend hit on the idea of renting San Francisco’s Carnegie Hall as a showcase for their talents. They hoped to impress the local drama critics, who would surely give them good reviews and launch their careers. Even with obliging friends to take publicity photographs and loan them props and costumes, the young women needed $40 to rent the hall and hire musicians. They had, Linda admitted, about 40 cents between them. But they did have a great deal of courage, so they went to the offices of Mayor James H. Phelan, a wealthy and sympathetic philanthropist. The mayor listened attentively to their story and loaned them money to finance the recital. As Linda said later, the show was a critical success, but their careers still languished.

A year after her appearance as a fishermaid, Linda got the role of the servant boy. That was the beginning of her friendship with D.W. Griffith, but success continued to elude the talented and hardworking young actors.

In the early years of the 20th century, San Francisco supported two good stock companies, and “Lawrence” Griffith managed to get work with both. Although he had little money, he did have a trunk full of manuscripts and plenty of ideas. In their free time, he dictated new poems and stories to his admiring young companion, who could not understand why a man of such obvious talent was still unrecognized at age 30.

Meanwhile, Linda’s career was moving steadily forward. She had a brief engagement as the leading ingenue for $35—an enormous sum at that point in her career. Then, too, the critics had begun to take notice of her. “An actress with more than looks,” said one reviewer. Soon she was sent to play ingenue roles at the Burbank Theater in Los Angeles. David managed to find work there, too, to be near her. When their engagements in Los Angeles ended, they returned to San Francisco with other actors from their companies.

But then came a parting. David got bits with a company due to return to the East, and he did so well with his small parts that he was assigned leading roles for the rest of the season. Early in the spring of 1906, David left California with the company, promising the unhappy Linda he would return.

On April 18, 1906, the great earthquake shook San Francisco, destroying more than 80 percent of the city and killing an estimated 3,000 people. Many, including Linda, lost all their possessions. Linda wrote to David in Minneapolis, telling him of the disaster. A week later, she had his reply. He suggested they meet in Boston, where his company was booked for six weeks. On May 9, dressed in ill-fitting clothes provided by the Red Cross and carrying a bunch of orange blossoms as a memento of her beloved California, she boarded a refugee train to cross the country.

Boston was another world for her, and it seemed an unsympathetic one. Apparently, no one cared what had happened on the West Coast. But David was there, and on May 14, 1906, they were on their way to the church when they realized he had forgotten to buy a ring. The cab driver made a quick detour by way of a jewelry store, and only minutes later the couple exchanged marriage vows in historic Old North Church. Linda Arvidson was now Mrs. David W. Griffith.

When the Boston engagement ended, Linda and David went to New York and moved into a tiny apartment. There was no work that summer, but in the fall, both were hired by a company—he as leading man, she as general understudy. While waiting for the play to go into rehearsal, David began writing a play called “A Fool and A Girl.” The “fool” was a boy from Kentucky; the girl was a San Franciscan. While David dictated, Linda took down his words on one of their few possessions, a second-hand typewriter.

The play they had been hired for failed, and it seemed that the Griffiths‘ first Christmas together would be anything but merry. But as they sat down to their simple Christmas Eve meal, Linda found a bit of paper under her plate. It was a check for $700, and the broad smile on David’s face told her the story: “A Fool and A Girl” had been sold!

Now Linda and David were in a happy daze. Their play was not due to open in Washington, D.C., for several months. Rather than looking for other acting jobs in the meantime, they decided to spend the time writing. Though much work was turned out, little was sold. By the time the play opened, they had only enough money for railroad fare to Washington. When the play closed after a week in the capitol and another in Baltimore, they returned to New York with not even a dollar left for a taxi.

Somehow, they got through the winter. Then a friend from early stock company days told them about money to be made in the “flickers,” as the new motion pictures were called. Although no self-respecting actor would be caught going to see a motion-picture show, much less acting in one, it was a way to earn money—as much as $5 a day. And a good story could bring as much as $15.

The Griffiths were in no position to reject the idea. Almost at once David got a job at American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. A few days later, Linda joined him. It seemed good business to David to keep their marriage secret, so Linda Arvidson and “Lawrence” Griffith told no one of their relationship.

The movie-making business soon dominated their lives. They were in only one film together, “When Knights Were Bold.” Then Lawrence’s career took a new turn: He became a director. When his first picture, “The Adventures of Dolly,” with Linda playing the lead, opened in July 1908, it was a success. He was given a contract providing for a weekly salary and a royalty. Linda later wrote, “Had he known then that for evermore, through weeks and months and years, it was to be movies, movies, nothing but movies, David Griffith would probably then and there have chucked the job, or, keeping it, wept bitter, bitter tears.”

It was different for Linda. She enjoyed the make-do philosophy of the crude studio, the regular income, and even the parts she played—“the sympathetic, the wronged wife, the too-trusting maid, waiting always waiting for the lover who never came back. But mostly, I died.”

And there was the camaraderie with other actors: pretty Gladys Smith with the golden curls, who later began to call herself Mary Pickford; Mack Sennett, who annoyed his fellow actors with his constant clowning; and eventually Lillian and Dorothy Gish.

But there was no social life in those days, nothing but making movies—“a good, hard, steady grind, and we liked it” —and making money. David’s royalty checks were amounting to $1,000 a month by the end of their second year at Biograph, and most of it went into the bank. The plan was to work and save for two or three years, then quit so David could write plays.

But in the summer of 1910, he signed his third Biograph contract, this time scratching out “Lawrence” and writing in David W. Griffith. By then he had begun to experiment: close-ups, panoramic views, shots from moving vehicles. While other directors were producing 1,000-foot reels that ran for only 12 minutes, Griffith was turning out two-reelers and then even longer films. He never used a script, working out everything in “mental notes” and rehearsing his actors relentlessly until each scene dovetailed with the next exactly as he wanted it.

Unfortunately, the stress of the two careers was too great for the marriage, and Linda and David began to drift apart. She was spending more time with other actors and actresses. In his free time, David wanted to be alone to write. Linda felt that directing was more important than writing; David disagreed. She wanted to continue playing ingenue roles; he often cast her in character roles, and when the strain between them became too great, he stopped casting her altogether.

In the summer of 1912, the Kinemacolor Co. of America, a subsidiary of an English filmmaker, began producing motion pictures in color. Kinemacolor started in Queens, but when it moved to California, Linda Arvidson decided to go with the exciting new company as its leading lady.

Not long afterward, D.W. Griffith also left Biograph. The company was declining, and Griffith felt the time had come to do something new, something big. So he made “The Birth of a Nation,” a three-hour milestone in motion picture history. When it was at last released in 1915, it marked the high point of D.W. Griffith’s career, which eventually included 432 motion pictures.

Kinemacolor closed a year after Linda joined the company, ending suddenly with the death of the company’s president. By then, there seemed nothing left of the Griffiths’ marriage. Linda returned to New York. Perhaps, she thought, she had worked long enough and hard enough. It was time to relax and enjoy life a little. David was prospering; her comfort was assured. Just as David’s career reached its zenith, Linda’s ended. However, her strong interest in the movies continued, and she kept in close touch with her actor and actress friends. In the 1920s, she gathered her memories and wrote a book, When the Movies Were Young, describing the early, frantic, and inescapably romantic days at Biograph.

The Griffiths’ marriage finally ended in divorce in the 1930s. On July 26, 1949, Linda Arvidson Griffith died at age 63, almost exactly a year after the death of her former husband. Although her later years had passed in wealth and comfort, Linda never forgot the early days of struggle. In retrospect, they seemed the most rewarding of her life. But she also had known many times of near despair, when life seemed overwhelmingly difficult, and she remembered the small but important turning points, such as the philanthropic generosity of Mayor Phelan of San Francisco. If it was possible to help others through some of their problem-ridden times, Linda Arvidson Griffith resolved to do so by establishing a fund in her will.