A legacy of vision, generosity, and American storytelling

Lila Acheson Wallace (1889-1984)

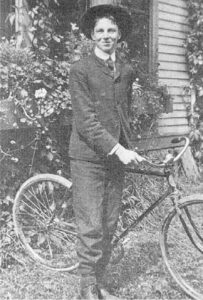

DeWitt Wallace (1889-1981)

He was a shrewd and innovative publisher.

She was a passionate philanthropist.

Together, they were one of the most influential husband-and-wife teams in mid-20th century America. As co-founders of Reader’s Digest, DeWitt and Lila Wallace altered the country’s reading habits. The tremendous success of their magazine and its many offshoots allowed them to generously support an array of organizations and causes, ranging from the Bronx Zoo to Outward Bound. Their story is one of hard work, commitment, and a dedication to sharing their wealth with others.

William Roy DeWitt Wallace was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, on November 12, 1889, the fifth of seven children. Home was a large frame house on the campus of Macalester College, where, over a 40-year span, his father, a professor of Greek, was teacher, dean, and president. Summers were spent on the shores of Lake Wapogasset, in Wisconsin, where the Wallaces had built a home.

After graduating from Mount Hermon School, he studied at Macalester for two years, transferred to the University of California at Berkeley, spent two years there, and then left without a degree.

Returning to St. Paul in 1912, DeWitt took a job writing sales promotion letters for Webb Publishing, a company that specialized in agriculture textbooks and farm magazines. During four years at Webb, DeWitt cultivated a somewhat unusual interest in magazine articles.

“. . . my chief ambition in life is to serve my fellow man.”

– DeWitt Wallace

He noted that the Department of Agriculture and a number of state bureaus had published hundreds of pamphlets containing valuable information for farmers. A great service for farmers, DeWitt reasoned, would be to alert them to all this information. The owners of Webb Publishing were not so sure but offered DeWitt a loan to try out his idea. He printed a 124-page booklet listing all the pamphlets, with a brief synopsis of each. Distributing copies through banks to farmer customers, DeWitt sold 120,000—enough to pay back his loan and break even.

DeWitt continued his condensing techniques, working next on a digest of ideas from marketing trade journals to sell to department stores. And he began to suspect that the public would be open to collected condensations of general interest articles.

In 1916, he took a job selling advertising for Brown & Bigelow, a large printer of calendars. But in 1917, the United States entered World War I and DeWitt enlisted. At the Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918, he was hit by shrapnel in the neck, back, and shoulders. He spent his convalescence reading and condensing magazine articles. When he was discharged in 1919, he returned to St. Paul and for six months studied magazine stories at the Minneapolis Library.

DeWitt had met Lila Bell Acheson several years before during Christmas vacation in Tacoma, Washington, when he was visiting the home of a college friend, Barclay Acheson, Lila’s brother. She was born in Virden, Manitoba, Canada, the third of five children of the Rev. T. Davis Acheson and the former Mary Huston. Her father, a Presbyterian minister, soon moved his family to the United States and brought them up in a small Midwest town. Lila’s high school years were spent in Lewiston, Illinois. Later she studied at Ward-Belmont School in Nashville, Tennessee, and at the University of Oregon in Eugene, where she completed the four-year Bachelor of Arts course in two and a half years. After graduation, she taught high school for two years in Eatonville, Washington, and helped manage a YWCA summer home on an island in Puget Sound.

During World War I, the YWCA became concerned about the many women working in factories. With the U.S. Department of Labor, the “Y” developed a program to improve women’s working conditions and help them after work as well. Lila was sent east to organize recreational centers for working women. At a large munitions plant in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, she helped create a social center where music and recreational programs were introduced. For the first time, hot meals were served to night-shift workers.

After the war, Lila continued in social work and was sent by the Labor Department to other industrial centers. In New Orleans, she organized classes for women factory workers in music, languages, homemaking, and the arts. Later, in small towns, she made public speeches and arranged meetings to persuade canning factory owners to build schools and recreation centers for migrant workers.

In 1920, while she was living and working in New York City, Lila was asked to help establish a YWCA for industrial workers in Minneapolis. There she spent a great deal of time with DeWitt, with whom she’d been corresponding since they had met several years earlier.

On October 15, 1921, Lila and DeWitt were married in Pleasantville, New York. Barclay Acheson, who was by then a Presbyterian minister, officiated. The marriage was not only a commitment to each other, but also to his idea for a new magazine. The young couple put together the first issue of Reader’s Digest in an office under a Greenwich Village speakeasy with money borrowed from relatives. Working long hours, mostly at the New York Public Library, DeWitt and Lila selected and condensed articles from a wide variety of magazines.

In late 1921, they mailed a letter to a list of friends and names they had compiled from numerous mailing lists soliciting subscribers, and then went on their honeymoon. When they returned, they had a list of 1,500 subscribers. Five thousand copies of Volume One, Number One were printed in February 1922 at 25 cents a copy. The new magazine was an enormous success. Within two years, subscriptions had nearly quintupled (and all the loans were repaid). In 1926, Reader’s Digest had 30,000 subscribers; in 1929, 290,000.

Early on, DeWitt began placing articles in other periodicals with an eye toward condensing them in the Digest. He also commissioned original pieces for Reader’s Digest. “—And Sudden Death,” which appeared in 1935, became one of the most widely read magazine articles of all time. It described in grisly detail the horrible death resulting from auto accidents. That article, conceived by DeWitt, was largely responsible for gaining the Digest its reputation as a public interest magazine, and by 1939 circulation had climbed to more than 3 million. That same year, DeWitt and Lila moved Reader’s Digest headquarters into a new Georgian-style red brick complex in Chappaqua, New York.

“The Facts Behind the Cigarette Controversy” appeared in 1954 and was the first of several pieces commissioned by the Digest to examine the relationship between smoking and cancer. In fact, after Reader’s Digest introduced advertising into its magazine in 1955, Wallace never permitted tobacco ads. Ballooning production costs made the decision to include advertising necessary, but before he did, he polled subscribers to find out whether they wanted higher subscription rates or advertising. Advertising won overwhelmingly. Ads for alcoholic beverages were also barred from the U.S. edition for years, but in 1978, citing changing social conditions, the magazine began selling wine and beer ads and, in 1979, ads for liquor.

DeWitt Wallace’s editorial philosophy strongly reflected his political views, which were conservative Republican and anti-Communist.

He was close to Presidents Eisenhower and Nixon, and in 1972 President Nixon celebrated the 50th anniversary of Reader’s Digest with a white-tie banquet at the White House and the presentation to DeWitt and Lila of the Medal of Freedom, the highest honor the United States can bestow on a civilian.

When the Wallaces gave up active day-to-day management of their publishing empire in 1973, the Digest had a worldwide circulation of 30 million and was one of the world’s largest publishers of books and recorded music.

The couple lived quietly on 100 acres of hillside they had purchased during the Depression that overlooked Byram Lake in Mount Kisco, New York. On this land they built their home, which they called “High Winds,” a three-story stone building with turrets, designed and decorated by Lila. They tended to avoid large social functions, preferring to host small dinner parties at High Winds. Once a week or so, DeWitt accompanied Lila to New York to attend the theater or a concert.

An advocate of physical exercise, DeWitt got his in a manner he considered more productive than a round of golf: with a pick, shovel, and a wheelbarrow he worked on the roads that crisscrossed High Winds. When the roads needed oiling, he went to local service stations and bought used crankcase oil.

Frugality suited him. So did generosity. Not long after the magazine began returning sizable profits, DeWitt established a trust fund for 32 relatives. In 1933, he presented his father with the keys to a new home, a bungalow in St. Paul that he and Lila had secretly bought and furnished.

DeWitt bestowed many gifts quietly and unexpectedly. He once slipped an envelope into the pocket of Joshua Miner, president of Outward Bound U.S.A. This program of individual accomplishment and self-realization through strenuous outdoor activity and adversity matched Wallace’s philosophy perfectly. As Miner tells it: “Lunch over, we said our thanks and goodbyes. Going down the elevator, someone said, ‘What’s in the envelope?’ I opened it. Inside were a letter and a check for one million dollars.”

Lila’s philanthropic impulses were oriented more toward the arts. One of her major interests was the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the Museum’s Great Hall was being restored, she came in once a week to monitor the progress. When the hall was completed, she established a permanent fund for fresh flowers in the four niches in the Hall. She said it gave her great pleasure to ensure that the Great Hall would always include “living beauty.”

She also had a special love for Egyptian art, and demonstrated it by helping the Met with an extraordinary gift. In 1983, its rich collection of Egyptian art—nearly all of which had been inaccessible to the public—went on permanent display in 32 galleries named in her honor.

Lila’s appreciation for the arts extended to the performing arts as well—to dance, drama, and music. For 12 years, she served as a trustee of the Juilliard School to which she donated money to construct a library, create programs for young conductors and playwrights, endow chairs for distinguished teachers of drama and music, and bring renowned artists, such as Callas, Balanchine, and Rostropovich, to instruct, lecture, and perform. She also contributed generously to Lincoln Center by endowing chairs at the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, and the Chamber Music Society, and by sponsoring new works at the New York City Ballet and New York City Opera.

She was also fascinated by birds and gave the New York Zoological Society a gift of $5 million to construct the “World of Birds,” where birds ranging from great hornbills to tiny hummingbirds fly free in environments that simulate swamps, grasslands, jungles, and rain forests.

In 1981, at the age of 91, DeWitt died in his sleep at High Winds. Three years later, Lila died, also at home.

Many of DeWitt and Lila’s gifts were made through funds set up in The New York Community Trust. Today, these funds continue their astonishing generosity.