Advertising exec placed “car cards” and posters where travelers would see them. Fund at The Trust supports scholarships.

LeMoyne Page (1900-1964)

Hard working. Determined. Competitive. Even at times controversial. That was LeMoyne Page. Creative. Inventive. Devoted to family, friends, and community. That, too, was LeMoyne Page.

In a 30-year career in advertising, he sold more than $100 million of ad space. His specialty was transportation advertising, and the firm he established in the middle of the Depression, Transportation Displays Inc., generally known as TDI, was so successful that at the time of LeMoyne’s death at age 63, his company was the recognized leader of the transportation advertising industry.

Francis LeMoyne Page was born in Pittsburgh in 1900. His father, Benjamin Page, was founder and president of The Pennsylvania Trust Company, a Pittsburgh banking establishment. His mother, Mary LeMoyne Page, was the granddaughter of Dr. Francis J. LeMoyne, a physician and prominent 19th-century abolitionist from Pennsylvania.

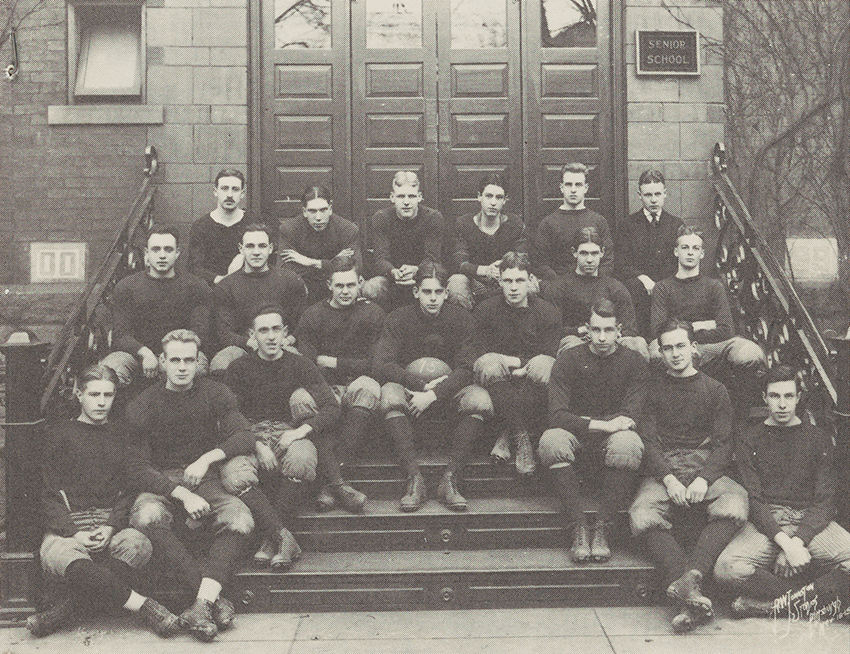

LeMoyne, as he was called, received his preparatory education at Shady Side Academy in Pittsburgh and The Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut. At Choate, he was an ardent member of the crew team and represented the crew at graduation, when he delivered his first public speech—a milestone he recorded in his diary. The date was May 29, 1918; the setting was a dinner banquet. “We will always look back on our crew,” LeMoyne declared, “as an incentive to pull together with the best Choate spirit in every race!”

From Choate, LeMoyne proceeded to Princeton. Caught up in the patriotic fervor that first semester (the fall of 1918), he joined the Princeton Color Guard and spent hours attending to the Guard’s uniforms and other details. He attempted several times that semester to join the Officers Training Corps but was informed each time that he was too young. In November, the Great War ended, and LeMoyne’s interest turned, once again, to sports and academics. He became a member of the varsity crew, wrestling and football teams; still, he had time to be business manager of The Princeton Tiger, the college humor magazine first published in 1882.

LeMoyne’s major at Princeton was architecture, and in his senior year he was offered a scholarship to continue studying architecture in Paris. A number of LeMoyne’s friends and advisers urged him to accept the scholarship and make architecture his career. But back in Pittsburgh, Benjamin Page wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. And that is what LeMoyne did—or, at least, started out to do.

He returned to Pittsburgh after graduation and went to work at his father’s bank. He became secretary, and then director of the Pennsylvania Trust Co. during the boom years of the 1920s. LeMoyne was working in the bank’s advertising department, where he put into practice his belief that, contrary to the prevailing conservative type of “tombstone” advertising employed in the world of finance, appeals to the public should be more aggressive and hard-hitting. In fact, LeMoyne had written a paper advocating this position while he was studying at Princeton.

Although architecture wasn’t the career he had chosen, it became, for the rest of his life, a weekend occupation, an after-hours commitment to one or another design and construction project. The first was the reconstruction of a pre-Revolutionary log cabin in Pittsburgh’s Fox Chapel district. Another was the conversion of an old stone grist mill in Mendham, New Jersey, into a home.

LeMoyne’s most ambitious building enterprise took place over a period of 15 years on a small island in Long Island Sound, off the coast of Greenwich, Connecticut. There, he built a luxurious summer retreat, a complex whose design evoked a ship: The pilot house from an old tugboat constituted a “prow”; decks and catwalks connected other structures. LeMoyne’s last project was the renovation of the old white clapboard house on East 93rd Street in New York City, where he lived with his wife and children.

LeMoyne always kept busy with projects and ventures. In Pittsburgh in the 1920s, he formed a coal mining company, which afforded him another outlet for his energies as well as an opportunity to demonstrate a new method of soil conservation.

At the same time, he was learning to fly an airplane. That interest, too, grew into another business venture; soon he was president of an aviation company called Airways and Aircraft of America. The company was headquartered at Pittsburgh’s Bettis Field, and its booming business helped Bettis emerge as the city’s first commercial airport.

Even the depressed economy after the 1929 stock market crash became, for LeMoyne, a challenge to find new opportunities. In 1931, he moved to New York and joined the staff of Barron Collier, an advertising company that specialized in placing ads in streetcars and newsstands. Soon he had a lot of transportation advertising ideas of his own and, in 1934, left Collier and acquired an independent franchise to handle advertising for the New Haven Railroad. Already he was anticipating the burgeoning of the suburbs and the potential of the suburban railroads as a significant new advertising market. He personally led the service crew in placing “car cards” in the trains and posters in the stations. Business grew, and in 1938 LeMoyne formed Transportation Displays Inc. (TDI). His goal: to combine all the suburban railroads into a single new advertising package of high-income railroad commuters known as “TDI Commuter-Land.” In the early 1950s, TDI began installing advertising displays at airport terminals. In this way, LeMoyne felt advertising could reach a new intercity market of “managers-on-the-move.”

According to The New York Times, LeMoyne’s ideas “were not always popular, but they seldom failed to draw attention.” For example, the Times reported that LeMoyne Page “… initiated a short-lived program of music and commercials in Grand Central Terminal. It was expected to net the owners of the terminal $90,000 a year. But the public, led by Harold Ross, then editor of The New Yorker, protested at a series of stormy hearings, and the broadcasts were suspended.”

Controversy, however, did not hurt business. In 1964, TDI was selling ad space in all of New York’s commuter rail systems; in the rail systems of Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston; and in major airport terminals across the country.

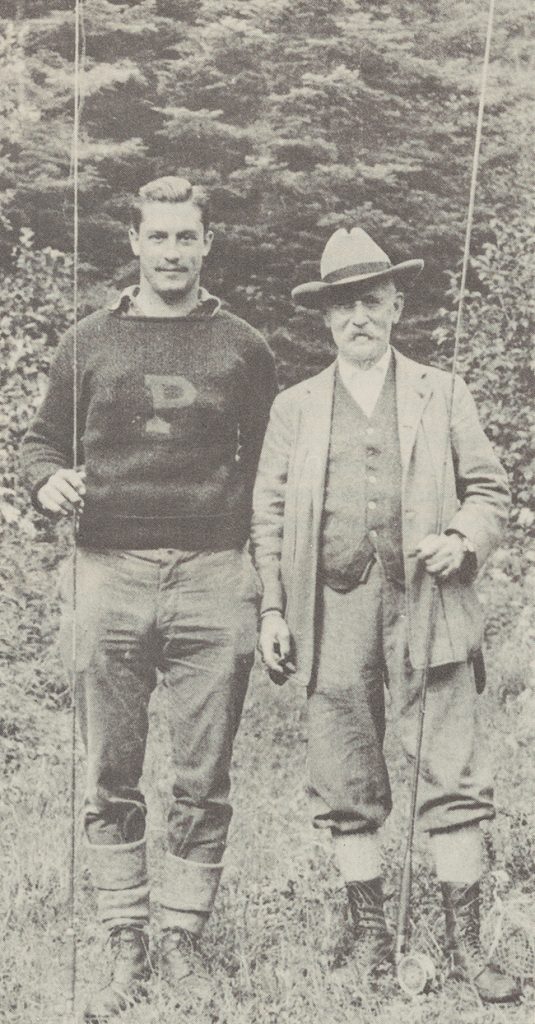

A physically powerful man, LeMoyne was almost 6 feet tall, with a heavy, muscular build. He was athletic and highly competitive. He possessed a determined will to do whatever job was on hand—whether it was moving boulders to bulwark his island home against the sea or seeking out and obtaining a new advertising franchise. Always the individual, he wore bow ties exclusively … and never an overcoat or hat. When the weather grew cold, LeMoyne Page settled for adding a vest and gloves.

In 1921, at Princeton, LeMoyne had written in a diary (under the heading, “Things that I have always wished for”), this goal: “To have a family ranging from four to ten … To make my home complete and entirely happy within itself.” Thirty years later, his wish began to come true.

In 1953, LeMoyne married Dorothea Fiske. (They had met when she came to work at TDI in the ’40s; she had since left the company.) In 1955, the first of their four children was born, a son named Francis LeMoyne, Jr. Susan Mary followed in ’56; Pamela Oldham in ’58; and Peter Fiske in ’59. LeMoyne doted on his family and in making their new home comfortable. In 1957, they had moved from an apartment to an early 1900s house on East 93rd Street. The house needed renovation and became LeMoyne’s pet project: He installed bathrooms, built a pantry, unblocked the fireplaces. He accomplished most of the work alone.

But LeMoyne did not have many years to spend in his new home with his family. In 1964, he suffered kidney failure after an operation. One week later, he lapsed into a coma. Seven weeks later, he died.

The funeral was held at the Brick Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, where LeMoyne had been deacon and president of the Men’s Council. Other organizations also had benefited from his help. For 25 years, LeMoyne Page chaired the Graduate Council of The Princeton Tiger; he had served as president of the Alumni Association of the Choate School and as a member of the school’s board of trustees. In addition, at the time of his death, he was a member of the University Club, the New York Yacht Club, the Rockefeller Center Luncheon Club, and the Princeton Club in New York.

In his college diary, LeMoyne Page wrote, “Creation is a process, not a product.” In a way, his words live on. The F. LeMoyne Page Memorial Fund was established in The New York Community Trust by his brother, Benjamin Page Jr., to make awards each year to students who demonstrate outstanding creative achievement.