Professor fired for her gender and religious beliefs, rallied for women’s rights.

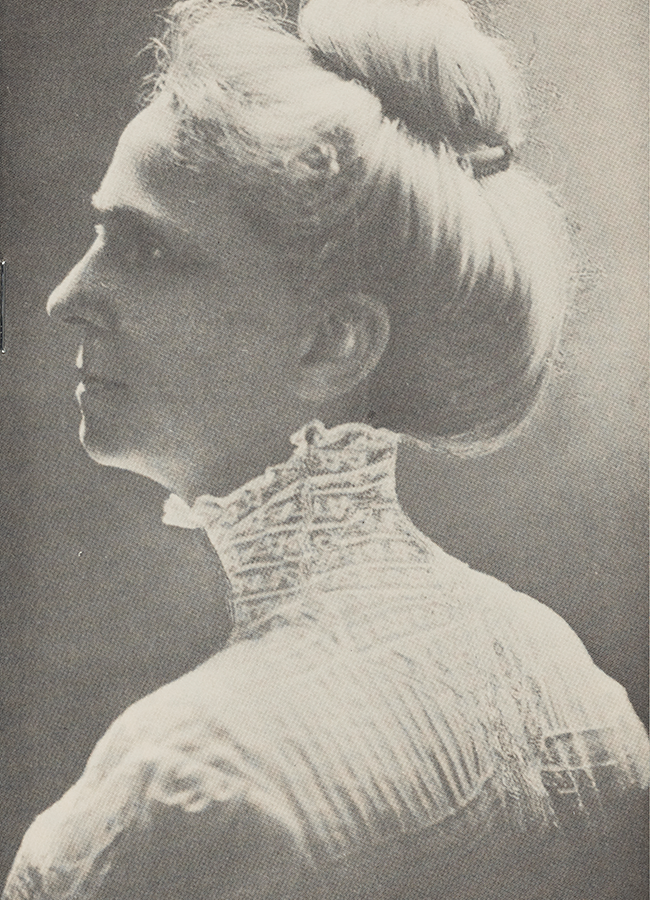

Kate Stephens (1853-1938)

It was a warm June day, “good Kansas weather,” the local people said. The year was 1879. The president of the University of Kansas beamed at the young woman visiting his office. For the past year, she had worked at the university as assistant professor in Greek. “Miss Stephens,” he said, “it is a real pleasure to tell you that you have been appointed full professor, and I want to announce your name as head of our Department of Greek.”

She was only 26. Five years before, the job that was now hers had belonged to her beloved fiancé, who had died.

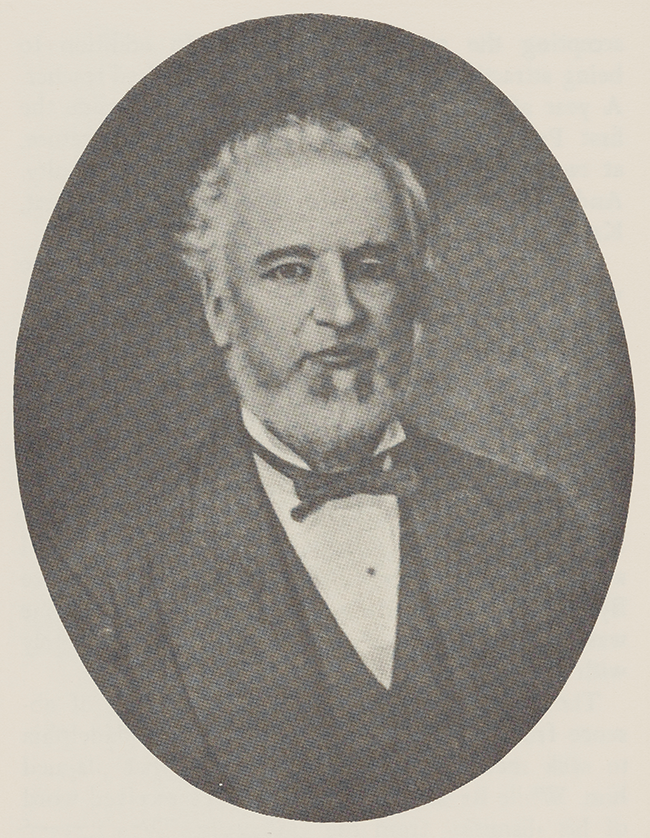

Kate Stephens was born in Moravia, New York, on February 27, 1853. Her father, Nelson Timothy Stephens, gave up his law practice in 1861 to raise a company of volunteers to fight in the Civil War. Illness forced him to resign, and when his strength did not return, his doctors recommended a horseback trip to the West.

In 1865, Nelson Stephens arrived in Lawrence, Kansas, a thriving community in the midst of rich farmland and the home of the new University of Kansas. He bought 250 acres near Lawrence, and in 1868, he went back East to bring his wife, the former Elizabeth Rathbone, and four children to their new home.

The Stephens family thrived in Kansas. The farm prospered, and Kate’s father joined a law firm and later became judge of the Circuit Court of the Fourth District of Kansas. For Kate, it was a happy life of ease and comfort and intellectual stimulation.

Reading aloud was a custom in the Stephens family. With strict guidance from her father, Kate read prodigiously from early childhood. She spent much time with him discussing her ideas about evolution or listening to him discuss political and legal ideas with his friends. When she was 12, he wrote to her: “Don’t learn simply to recite, but learn so as not to forget. I want you to be not only equal to those you meet, but superior to them. Never be satisfied with an equal amount of knowledge with others. When you have more than others you can help them and command the respect your helpfulness will bring. Learn, then. Strive to do more than others and be helpful in your superiority.”

Kate was 15 when her family moved to Kansas and entered the junior preparatory class at the University of Kansas. Three years later, in 1871, she enrolled in the university as a freshman in the Classical Course, a curriculum embracing the arts, sciences, philosophy, and classical languages, including Greek.

“I was starting the sophomore year and feeling exceedingly unknit in the knowledge of Greek,” Kate recalled years later. “I worked so hard the pages of the oration would become photographed, so to speak, upon my retina, and when I went to bed at night with problems unsolved, I would bring the pages before my mental eye and lie there in the dark and study out solutions…”

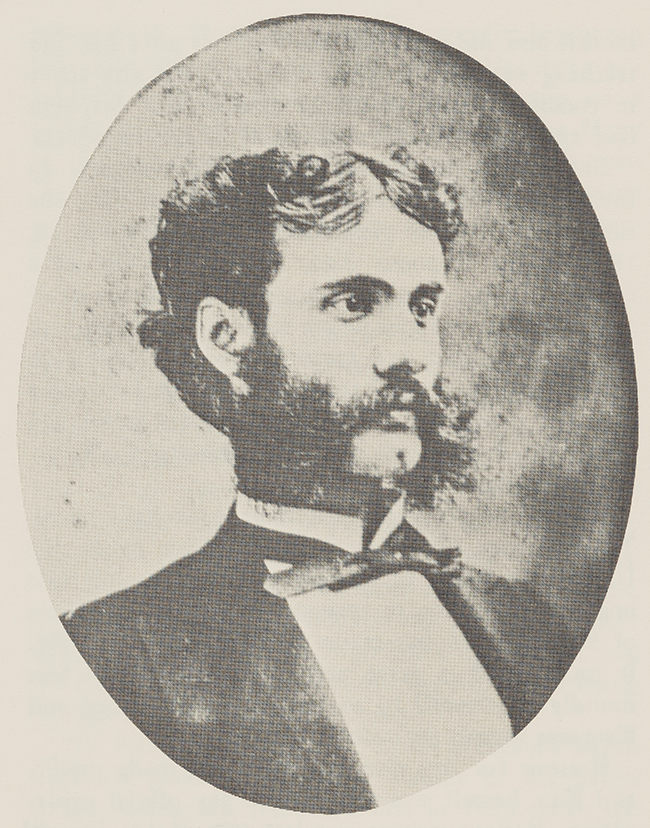

That year, Kate had a new instructor in Greek. He was Byron Caldwell Smith, who had received his degree from Illinois College at age 19 and had studied for four years in Europe before accepting the position in Kansas. He was outgoing and a gifted teacher. A year after his arrival at the University of Kansas, he was made the first professor of Greek Language and Literature—at age 24, the youngest member of the faculty. And he fell deeply in love with his student Kate Stephens.

Kate was as serious outside the classroom as she was in it, generally preferring discussions of evolution to dancing, but she had become fond of one of her classmates, Ned Bancroft. Professor Smith, believing Kate and Ned were engaged, kept silent about his feelings for her until one May morning in 1874, when he informed his startled student that he was leaving the university because he could not stay and see her engaged to someone else. The declaration apparently clarified her own feelings, and a month later, during school vacation time, she wrote to Byron Smith from Auburn, New York, where she was visiting, that she had broken off completely with Ned Bancroft.

The following winter, Byron took a leave of absence from the university and went to Philadelphia to seek medical advice for an illness that plagued him. While he was in Philadelphia, he received word of his dismissal from the university. The cause of dismissal was generally attributed to his unorthodox religious beliefs: Skepticism in a state institution was frowned upon. Smith regretfully turned to editorial work and got a job at The Philadelphia Press. He and Kate began to make plans for a wedding in February 1876.

Kate was graduated as valedictorian with the Class of 1875 and immediately began graduate work, specializing in the study of Greek. The letters, both passionate and practical, streamed between Philadelphia and Lawrence. But in December 1875, two months before the wedding, Byron came down with pneumonia. Illness clung, and the marriage was postponed. Tuberculosis was diagnosed in April, and on the recommendation of doctors he went to Colorado. For a year, his condition continued to deteriorate, and his strength ebbed, but the letters never stopped, and the ardor expressed in them seemed to grow stronger. On March 8, 1877, Byron wrote his last letter to Kate. “If my unsteady hand finishes this page, Katherine, my treasure, it will be all I can hope. My condition is worse only in that I suffer more… You must not stop your blessed letters to me, darling, because I cannot answer them.” He died in Boulder, Colorado, on May 4, 1877, and a part of Kate Stephens died with him.

For many years after Byron Smith’s death, Kate struggled to regain her own health. She could not speak of her loss. But despite grief and illness, she completed work for her Master of Arts degree in June 1878, a year after Byron’s death. That autumn, she became assistant professor in charge of Greek Language and Literature at the university. In 1879, she was made full professor and head of the Department of Greek—the position that had been Byron’s. She was 26. Students found her an inspiring teacher. She was in complete command of her subject, and she knew how to communicate both her knowledge and enthusiasm to her students. A former student recalled, “She went beyond grammar—though we got that, too, to the civilization and life of Greece. Grammar was a means to an end; the end was the understanding and thrill and stimulation of the people and the age.” Byron Smith served as her teaching model, and she patterned her methods after his. But teaching was not her whole life. She also was active in community and university affairs. Kate Stephens apparently had found contentment, if not happiness.

But it was not to last. Her mother became an invalid, and Kate was not well. In 1882, she suffered a “nervous breakdown.” On December 24, 1884, Judge Stephens died, and Kate wrote to a friend, “To me, who was his constant companion, all that is noblest and best in life seems to have vanished. His great wisdom and great love were always such a ready refuge! And I think so often of his tender care and patience. . . I think how much better if I were lying there beside him than suffering this feverish imbecility of life.”

Kate’s fortunes continued their downward spiral. Three months after Kate buried her father, the university’s Board of Regents informed her of their unanimous decision to request her resignation. News of her dismissal was made public on May 1, 1885. It touched off a great uproar, for the action was roundly condemned by students and community, and Kate was warmly defended.

Reasons for her dismissal were not made public, and Kate was never given any official explanation. Various rumors circulated, but Kate thought she knew the truth. “The real grounds are my sex and religious convictions, or a lack of religious convictions, I suppose it would be put,” Kate wrote to a newspaper. “The fact that I am a woman is a casus belli to some members of the board, and that I do not belong to the Communion or Congregation of any church is a grievous sin in the sight of certain others.” Certainly Byron’s dismissal some years before had been based on the religious reason; and Kate was well aware that, despite her position as department head, her annual salary of $1,250 made her the lowest-paid member of the faculty—an indication of her status as a woman.

Kate left the university in June 1885, and that fall, she moved with her mother to Cambridge, Massachusetts. Income from the sale of their farm in Kansas and from her father’s investments allowed her to live in comfort. But in 1889, financial reverses resulted in the loss of her income. Reduced circumstances forced her to break up her household, take a room in a boarding house, and find a job.

She was hired as a junior editor at a textbook publishing house, D. C. Heath and Company, beginning a long editorial and writing career. Her first project was working with Charles Eliot Norton on a series of five graded readers for children, “The Heart of the Oaks” books, for which she was paid $1,000. (She noted later that “they had a large public, sold by the thousands, and brought in considerable money.”)

In 1894, Kate moved to New York City, where she plunged into her busiest and most productive years. She did editorial work for several major publishing houses. She wrote innumerable articles and book reviews for magazines and newspapers. And she published books of essays, poetry, and fiction, as well as an autobiography. In 1927, at age 74, she set up The Antigone Press in her apartment, and published several of her own books. “So it is,” she wrote, “the same old story—work, work, work. That has become my pleasure. I have known little else for so long that I should feel odd not to know something was driving me. Not a rising sun has found me in bed for years.”

The books most important to her concerned Byron Caldwell Smith. One was a volume of his letters to her, which she first published in 1919 under the title “The Professor’s Love—Life, Letters of Ronsby Maldclewith” (an anagram of “Bryron Caldwell Smith”), carefully changing names and places. In 1930, she permitted a second edition, “The Love-Life of Byron Caldwell Smith,” to be published without the protection of anonymity.

When author Frank Harris, who had been a student of Smith’s and an acquaintance of Kate’s at the university, wrote an unflattering portrait of Byron Smith in “My Life and Loves,” Kate was infuriated. Determined to expose Frank Harris, whom in her more generous moments she labeled a “sort of literary saxophone, or Sousa’s band,” and to restore the good name of the revered Professor Smith, she wrote “Lies and Libels of Frank Harris,” which appeared in 1929.

Kate’s years in her bare little workroom in New York were solitary and work-filled, but her interests extended in many directions, from the need for a better card-cataloging system in public libraries to the sanitary conditions of public drinking fountains. Two interests were particularly absorbing and frequently overlapped: the status of women and the University of Kansas.

All through her adult life, Kate Stephens had been a believer in the cause of feminism, and as years went by, she became increasingly active.

In 1894, Kate had gone back to Lawrence to make speeches on women’s rights and woman’s suffrage. In 1908, she began to organize a movement for the appointment of a female member of the University of Kansas Board of Regents. Kate spent that summer in Lawrence organizing her campaign, and by fall had secured the signatures of most alumni and the petitions of former students. However, it was five years before a woman finally was appointed to the board.

In the years between, she continued to write and make speeches about women’s rights, and in 1911 and 1912, she worked with the Women’s Political Union, writing mottoes for the banners suffragettes carried in demonstrations.

In 1935, when Kate was 82, she returned to Lawrence, this time to stay. She spent many hours talking with old friends, visiting scenes of her youth, and walking miles to the cemetery where her family was buried. On her 85th birthday, Kate’s friends honored her with a reception attended by 115 guests. A month later, she suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, and on May 10, 1938, she died.

Despite her earlier financial struggles, Kate had built a small estate. By a trust agreement, she established the Stephens Bequest to be administered by The New York Community Trust in memory of her parents. In tribute to her father, she wrote fondly of his “learning in and faithfulness to the laws of the Eternal and of man, his loyalty to our American institutions and his endeavors for the ethical advancement and stabilization of the state.”

Photos courtesy of the University of Kansas Library Archives.