Inventor of innovative and popular shorthand dictation system.

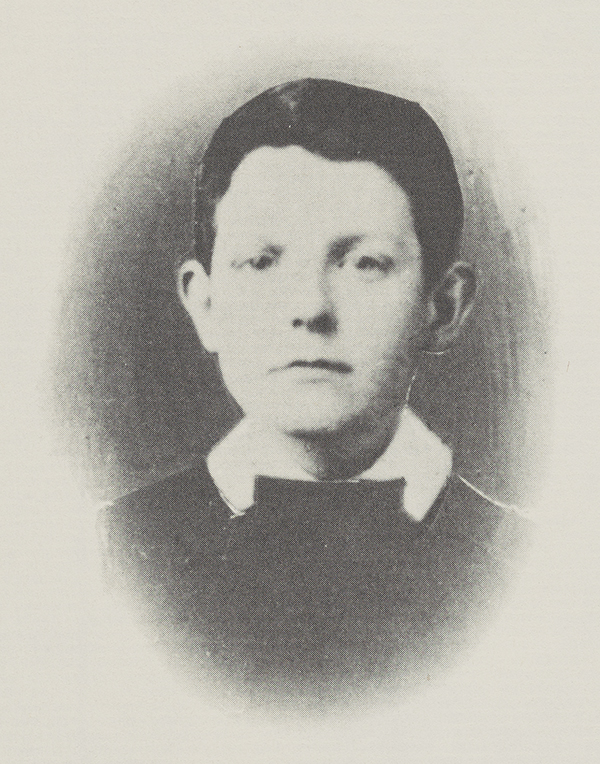

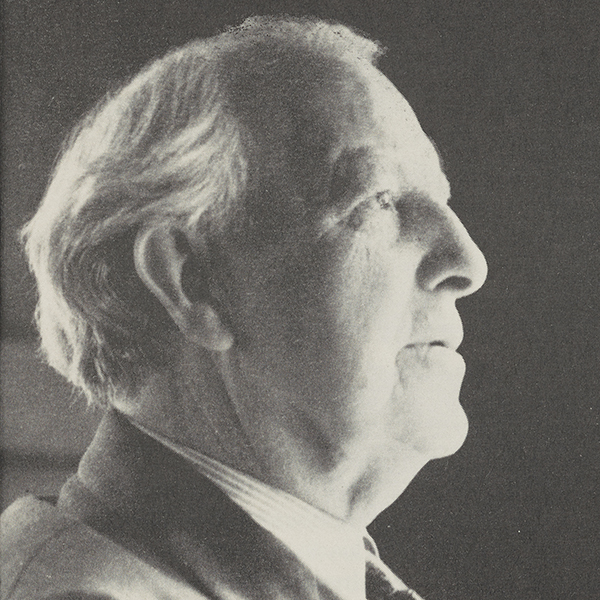

John Robert Gregg (1867-1948)

When he was a boy, everyone called him “Poor John,” the slow child who would “never amount to anything.” But John Robert Gregg refused to fulfill this dismal prophecy. Instead, it spurred him to find hidden talents, hone them, and, with unwavering determination, achieve world prominence and success.

On June 17, 1867, John Robert, the youngest of five children, was born to Robert and Margaret Gregg in a humble, three-room house in Shantonagh, Ireland. John’s father was a descendant of the proud McGreggor clan, wealthy landowners of the Scottish Highlands until they were dispossessed by the British government in the late 18th century. He emigrated to Ireland and in 1864 accepted a job as stationmaster at Bushford railway station, Rockcorry, in what is now the Irish Republic.

The Greggs were stern Presbyterians, and one of the values they instilled early in their children was the importance of study. At the small village school they attended, the older Gregg children were considered brilliant by their teachers, and, naturally, the same excellence was expected of little John, who joined the school in 1872.

But on John’s second day at school, when the schoolmaster heard him whispering with another child, he punished them by crashing their heads together so violently that John’s hearing was severely damaged. Fearful of further trouble—the wrath of his father—John did not tell his parents what happened, and the injury went untreated. The 5-year-old boy lost much of his hearing, and, because of this, his family and teachers supposed he was slow-witted. He became known as “Poor John,“ the backward child of whom little could be expected.

First Interest in Shorthand

One weekend in 1877, a family friend, a journalist, visited the Gregg family. On Sunday, the journalist accompanied them to the local church, where he took out his notepad and recorded the sermon in Pitman Shorthand. John’s father was greatly impressed, and believing his older children would benefit from acquiring such a skill, he supplied them with Pitman manuals. John, of course, was exempt, too “simple” to learn shorthand.

He later wrote of how deeply he felt the stigma of this label. But deep within him, he fostered a tiny seed of hope and belief in himself, and, perhaps out of a need to prove everyone wrong, he decided to teach himself shorthand. Being careful to avoid Pitman—which his bright siblings had quickly abandoned in disgust—he chose the slimmest textbook available in another system, Odell’s Shorthand.

John began to study shorthand, attacking the project with the extraordinary persistence and determination that marked his entire life. He immediately found his subject fascinating, and, to his delight, soon mastered it.

“I could teach myself shorthand because it didn’t involve hearing,” he wrote later. But sadly, John’s success went unnoticed by his parents, who probably thought the stenography was the wild scribbling of their “backward” child.

Another of John’s boyhood interests was tightrope walking, which he practiced on a rope tied between two posts in his backyard. These two interests—shorthand and tightrope walking—seem incongruous for a young boy, but, as it turned out, one of them one would shape his life and the other would save it.

In 1878, the Gregg family moved to Glasgow, Scotland’s principal commercial and industrial city. John’s father continued to work for a railway and by now, Samuel, the oldest son, was married and living in England. Fanny and George, the children next in age to John, were delicate, already marked for the disease most dreaded by 19th-century families—tuberculosis. The Greggs were poor, and it fell to John, a robust youth, to help the family income by getting a job. Thus, the man who was to influence and educate millions of people ended his formal schooling before his 13th birthday.

“No dull o’ brain”

About that time, an incident of great significance to John occurred. An elderly and much respected family acquaintance called on the Greggs and put some questions to John. When he failed to respond, his sister explained that John was “dull of hearing.” The old man patted John on the head and said, “Ah! Laddie—dull o’ hearing, but no dull o’ brain!” John was overjoyed. It was the first time anyone of importance had expressed confidence in his intelligence. Many years later, he wrote that those words changed his life, reinforcing his belief in his own latent abilities.

John’s first job was as an office boy at a law firm, working six days a week for wages of about a dollar. It was not the most challenging job. John’s duties were mainly sorting mail and receiving callers, leaving him with much time on his hands.

Compared to the drabness of village life in Rockcorry, Glasgow offered John a feast of intellectual stimulation. Soon the tall, handsome youth with the shock of wavy ginger hair became a familiar figure in the libraries and at the many free lectures offered in the bustling city.

John renewed his interest in shorthand. Using Pitman textbooks borrowed from the public library, he taught himself the system, which he found a disappointment, faulting its laborious angles, line positions and shadings as not only ungainly, but a great impediment to speed.

Although the use of shorthand dates as far back as Old Testament times, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, its popularity burgeoned. Many different systems were used in business, journalism, and academic institutions. While John was living in Glasgow, several magazines on the subject existed, often peppered with hot debates on their merits. John devoured these publications, exploring the major systems, all of which he found inadequate. Why not create a shorthand system that followed the slope of ordinary handwriting? he wondered. Such a method would be more natural to the human hand and, John reasoned, had to be faster.

Ideas that had simmered in his imagination for nearly a decade began to gel, and John went to work creating his own shorthand system. With typical enthusiasm and unflagging energy, he experimented with outlines based on the slope of longhand, with connecting vowels and without the complicated shading or position writing of other systems.

Teaching and Creating

About that time, he entered a shorthand speed competition and took first prize—a gold medal–even though he had never had a shorthand lesson in his life. Hearing of this, Thomas Malone, the owner of a leading shorthand school, offered John a part-time job teaching two evenings a week. John was grateful to add a few shillings to his meager income and proved to be a gifted teacher. Soon John began to express his dissatisfaction with the school’s system and showed Malone some of the work he had done to invent an easier shorthand.

Malone at once recognized the talents of this gifted young man and quickly adopted his ideas. He also persuaded John to collaborate on a book, promising him acknowledgment as co-author and a share of the profits. John was delighted and had not the slightest suspicion that Malone would not honor his promises.

From the start, the partnership was disastrous for John. He and Malone agreed they would each design an alphabet. But when John saw Malone’s outlines, he was dismayed. They were crude and unimaginative. Worse still, Malone rejected many of John’s most important innovations.

The new system they created was called Script. But when the textbook was finally published in September 1885, Malone copyrighted “Script Phonography” in his name, with no mention of John Robert Gregg as co-author. Malone also offered Script at his school, claiming to be its sole inventor. John’s hard work had brought only one reward—the realization that if he wanted to publish his own shorthand system, he would have to do it alone.

So, it was back to the journals, manuals, and endless experiments for a sadder, wiser, but more-determined-than-ever John. But just as he was at the height of his creativity, tragedy struck the Gregg family.

In March 1886, John’s brother George died of tuberculosis just a few days before his 24th birthday. Shortly afterward, his sister Fanny became incurably ill with the same disease, and, to John’s intense grief, died within a year. Devastated by the loss and unable to concentrate, John abruptly abandoned his shorthand project.

For a short while, he took a job as a journalist, writing an advice column for the lovelorn . But within a year, John resigned and moved to Liverpool, England, where his oldest brother lived. His job was promoting Script, with Malone’s agreement that he would receive half the profits of any textbooks he sold and would be free to set up his own school.

With his usual energy and youthful zest, John set up a small office in Liverpool and began whipping up interest in Script. Although he did not realize it, he was a remarkable salesman, and whenever he got the chance, talked to anyone who would listen about the advantages of shorthand. As a teacher, he was intuitive and patient, able to sense each student’s needs. In a short time, the Liverpool school was thriving.

Gregg’s Own “Light-Line”

Typically, Malone was ready to capitalize on John’s promotion of Script, and before long was trying to sell the copyright for a large sum, cutting John out. Outraged by the treachery of the man for whom he had worked so hard, John resigned and returned to the work he had put aside when his sister died. Testing his system by transcribing several speeches and articles from newspapers, he became excited anew by its fluency, simplicity, and beauty. He felt that his confidence in his work was not misplaced—the alphabet was superior to any he knew.

On March 29, 1888, John copyrighted his alphabet, which he called Light-Line, at the British Museum. Two months later, with the help of a small loan from his brother, the 20-year-old youth published his first textbook, Light-Line Phonography. The Phonetic Handwriting. John tackled the promotion of his new system with the same energy and enthusiasm he had for Script. On a tiny budget, he produced handbills, leaflets, and posters. Economy had some complications, however. Nevertheless, word of John’s new system spread, and students began to trickle into his modest school.

Soon the news was out—Light-Line Shorthand surpassed all others in speed and simplicity. It was said that if teachers could be persuaded to spend a couple of hours examining the system, they would be won over. Shorthand enthusiasts, intellectuals, and teachers praised Light-Line and acknowledged John had solved the problems that had preoccupied shorthand inventors for more than 2,000 years. Even Malone recognized the merits of Light-Line and had the audacity to allege John’s system was a plagiarism of Script.

John was on the road to success at last. Light-Line was favorably reviewed by the press not only in Britain, but in America, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia. But more adversity lay ahead.

In July 1889, Malone filed a lawsuit alleging Light-Line infringed on the copyright of Script. The claims were absurd but hurt John because he had to hire expensive lawyers. Yet, as much as he tried, Malone could not lay claim to Light-Line. In March 1890, John wrote jubilantly to a friend: “The Script action has been dismissed with costs. Fetch out the band and kiss the baby—and generally speaking do reckless things!”

An American Crusade

Interest in Light-Line was steadily growing in the United States, and John decided it was time to launch a personal publicity campaign there. After putting his affairs in order, in August 1893, John boarded a Boston-bound ship filled with emigrants. He was 26 as he began his crusade in the New World.

The America John found was far from prosperous. It was the year of the “Great Panic”—the worst economic depression since the Civil War. Boston suffered severely, with long lines of hungry people waiting for soup outside City Hall. Commercial life was sluggish, and most stenographers were unemployed. It could not have been a worse time to start a campaign for a shorthand system.

But John, as always, had confidence in his future, and, from his cheap lodgings in Boston’s Chinatown, began to promote the system he had renamed Gregg Shorthand.

Response was poor, and soon his funds were almost entirely depleted by the publication of textbooks, advertising, and other expenses. The bitter Boston winter of 1893 was John’s bleakest period. Twenty years later, at the Gregg Silver Jubilee convention in Chicago, he recalled his first desolate Christmas in the United States, when he and his agent, Frank Rutherford, had only $1.30 between them.

“Rutherford and I determined that we were going to do the best we could to have one good Christmas dinner. Late on Christmas morning, we walked down to a hotel—walked to save carfare—and had our dinner after carefully estimating the cost from the bill of fare. In figuring over the meal, we had reserved 10 cents for carfare home. But the waiter helped me on with my overcoat, and away went the 10 cents. We trudged home through the snow, and then Rutherford, who had a wife and family in England, played ‘Home, Sweet Home’ and other cheerful airs on the organ until we almost wept.”

This poignant story tells not only of John Robert Gregg’s early struggles but also of the kind of man he was—one who would give away his last dime. John’s fortunes did not improve in the first months of 1894. For weeks, he lived on free sample packets of Shredded Wheat, an experience that left a lifelong aversion to the cereal. By mid-April, things were so bad that John, depleted and disheartened by illness and hunger, almost crumbled. In a moment of desperation, he wrote a letter to the publishing house of Charles Scribner & Sons offering to sell the American copyright of “Gregg Shorthand” for $250. He received no reply. Many years later, when John had become a world-renown publisher, he found himself seated next to Charles Scribner at a convention. When Scribner complimented John on his phenomenal success, John responded, “I owe it all to you!”

Gregg Shorthand Success

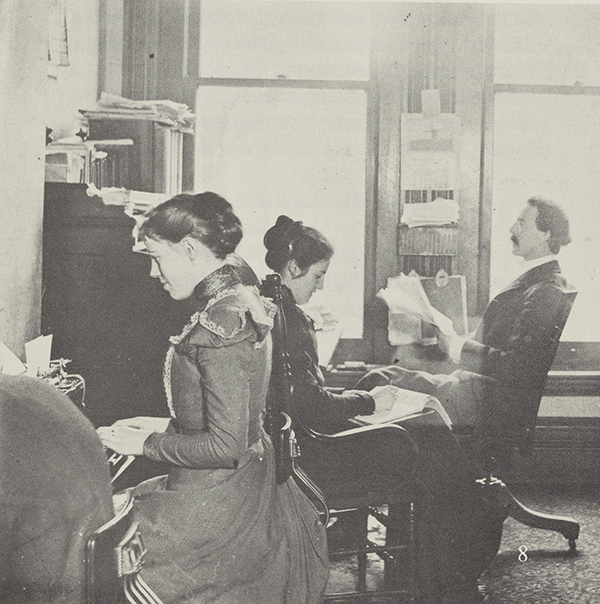

In the late spring of 1894, John picked himself up once more and began a new publicity campaign. Business improved enough to encourage him to move to Chicago, where he felt his prospects were better. He was right. As soon as he began his Chicago campaign, the response was gratifying. Teachers were more receptive than those in conservative New England, and John soon regained confidence in his future in America. With the zeal of a missionary, John worked tirelessly to gain converts to his system, and at last he was succeeding. Gregg Shorthand writers were winning speed contests all over the United States, and mountains of mail began arriving daily to congratulate its inventor. In 1896, John decided Chicago would be the permanent headquarters of Gregg Shorthand and his home.

In Chicago, a hobby of John Gregg’s led to his marriage. He collected quotations, especially enjoying those that encouraged ambition. It was while exchanging quotations with a Chicago newspaper that he met and fell in love with columnist Maida Wasson. They were married in the summer of 1899 in Hannibal, Missouri. Maida shared many of John’s interests and supported him immensely during his early years in Chicago.

The new century began well for John. More than 100 new schools were teaching his system, his marriage was happy, and he had settled so well into life in the United States that he became a citizen. About this time, he attended the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and heard William Jennings Bryan give his “Cross of Gold” speech. John immediately became a registered Democrat and remained one for the rest of his life.

On January 26, 1900, disaster struck. John was teaching an evening class in the fourth-floor classroom of his school when a fire broke out in a showroom downstairs. John and his students quickly exited the building by the stairs, and when it seemed that firefighters had the blaze under control, John returned alone to his office. This was a dangerous mistake. The fire had not been fully contained, and soon the stairs were ablaze, cutting off John’s means of escape.

The heat became intense, forcing him to climb out the window to a decorative ledge that ran the length of the building. Balancing precariously on the narrow strip, John remembered his tightrope walking as a child and decided to risk inching his way to the next building. A crowd gathered below, fully expecting him to fall. He concentrated, and, step by step, slowly walked to the end of the ledge. Opposite, on the same level, was a window, but between the two buildings was a 5-foot alley. John jumped across the gap, swayed momentarily, then grasped the mullion of the window and was saved. A local newspaper report on the dramatic escape ended with the comment: “Mr. Gregg’s loss is reported to be heavy, but it is hardly possible that it will seriously check his indomitable energy and determination as a teacher, author, and publisher.”

John did suffer a great loss in the fire. The only items saved were some charred files and a few textbooks that were locked in a steel cabinet. With such meager capital, John Robert Gregg began once again to rebuild his fortune. But he was no stranger to adversity, and his character was such that it seemed only to strengthen him.

John’s friends rallied to his support, and soon the school was flourishing again in a larger, more modern building. Interest in Gregg Shorthand had spread at such a rate that by April 1901 John wrote: “All through Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Missouri and Canada, Gregg Shorthand is now indisputably in the lead.”

The versatility of the system was demonstrated at the St. Louis World Fair in 1904, when a young man named Raymond Kelly was able to take dictation in 20 different languages from foreign visitors, successfully reading back the phonetic symbols he had written.

New Horizons in New York

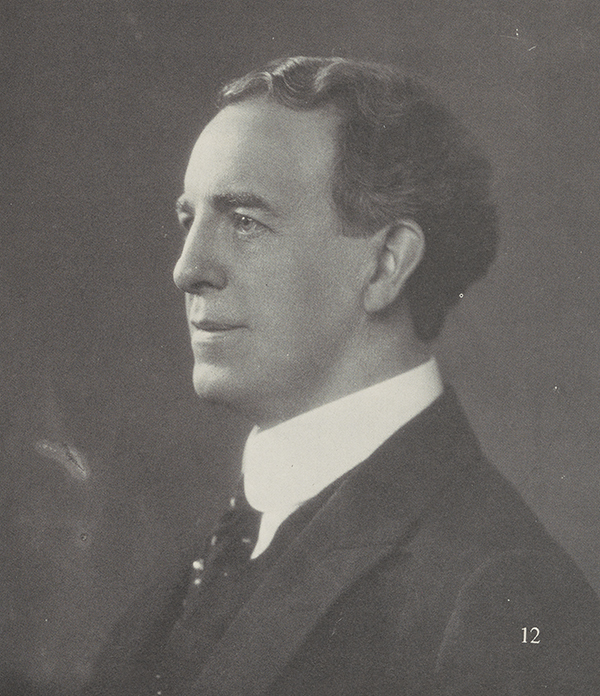

During his years in Chicago, John had been so busy there was little time for socializing. He loved good company, but his long hours and frequent travels gave him little time to enjoy himself. He was approaching 40 and had reached the point where his company could be placed in the careful hands of his dedicated employees. He decided to open an office and live in New York, where he planned to allow himself, at last, some well-earned recreation time.

John and Maida became involved with the National Arts Club of New York, established to promote artists and bring them together with art lovers. Although John was not an artist himself, he had a great affinity for creative people and helped them with his time, business experience, and financial support. John’s love of the arts was shared by Maida, who presided over a salon at their home where theater people and authors, including the well-known short-story writer O. Henry, often met.

Because he had known so many years of poverty, John was generous to others after he became successful. Neither of his brothers had prospered, so he helped them by enabling their children to come to the United States, where they were given jobs in the Gregg Publishing Co. John was a fatherly employer, rarely firing anyone. Yet, he was cautious of “spoiling” young people by paying high salaries too soon, feeling they should prove their competence and earning power first. If an employee wanted to buy a home, however, John often advanced a mortgage loan, and at a time when health insurance was practically nonexistent, he paid his workers’ medical bills. Nor did John forget those who had shared leaner times with him. Once, on hearing an old associate was down and out, he gave him a pension for life.

When World War I broke out, John became involved in volunteer work, the most interesting being counterespionage. The CIA discovered that German spies were exchanging information in a handwritten code they suspected was a form of shorthand. They consulted John, who identified and decoded the system. After the war, John was warmly thanked by the U.S. government for his services.

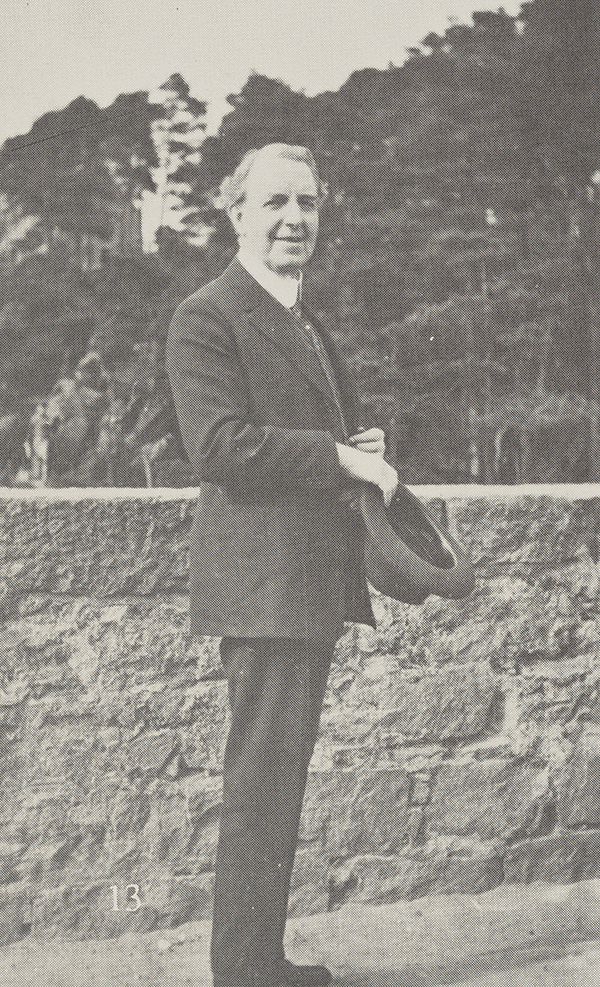

In 1922, John bought a chain of 33 schools in Britain, and during the 1920s continued to work at an exhaustive pace—lecturing, writing, and often crossing the Atlantic to oversee his schools. Wherever he went, he impressed all he met with his enthusiasm and often was asked the formula for success. He summarized it in five words: “analyze, organize, deputize, standardize, energize.”

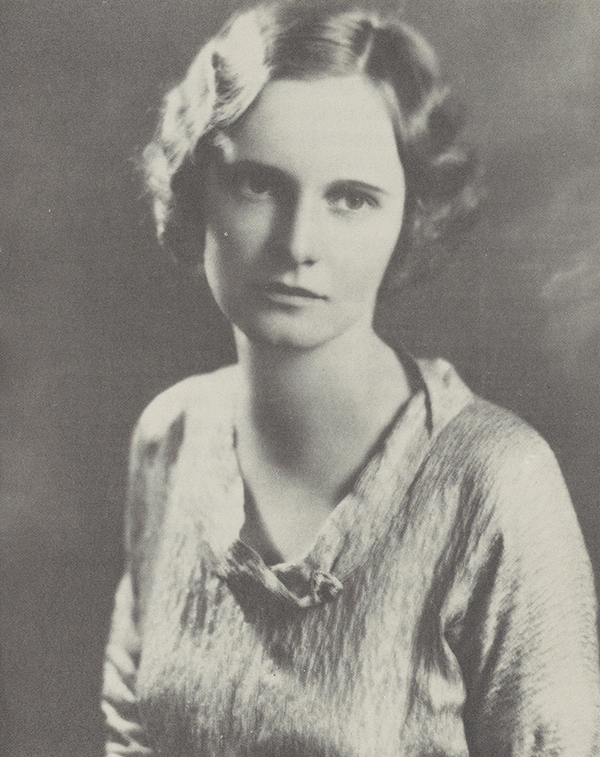

John had learned to relax in his middle years, spending pleasant evenings at the National Arts Club, where he loved a good game of pool. He and Maida usually combined their trips to Europe with side cruises, one of which had special significance in John’s life. On a Mediterranean cruise in 1925, they met Kate Kinley, the wife of the president of the University of Illinois, and her daughter, Janet. Later, the Greggs and the Kinleys kept up friendly correspondence.

Joys and Sorrows

In 1928, the Gregg Shorthand Convention, celebrating the 40th anniversary of Light-Line’s invention, was held in Liverpool, England, where it all began. For John, the event was overshadowed by the death of his brother Jared, and by anxiety over Maida’s health, which had been poor for almost a year. Although she insisted on traveling to England for the convention, Maida became too ill to attend the celebration dinner. She died in London on June 28, 1928. Terribly shocked and with great sorrow, John sailed for New York with Maida’s body. What had begun as a journey of triumph turned into one of tragedy.

John expressed the intense loss he suffered when he spoke of Maida at the Liverpool convention: “She has been beside me—not behind me—for the last 29 years. From the moment we married, success seemed to come my way. I attribute that very largely to her wise counsel, her sympathy in good times and bad times, and her admonitions.”

For the next two years, John diverted himself from pain and loneliness with much activity, traveling all over the United States and to Britain and Holland. He went on an extended visit to Cuba, where he and Maida had bought a home several years before. On his return, John learned that Boston University was to confer on him an honorary Doctor of Commercial Science degree. At the ceremony, he met Janet Kinley again. There was much to talk about, and that evening, Janet and John enjoyed each other’s company at dinner.

John spent the summer in Britain, and when he returned to New York in the fall, he moved his headquarters into a luxurious new suite at 270 Madison Ave. On October 23, 1930, John married Janet Kinley. The wedding was in Gallup, New Mexico, at the home of Clinton Neal Cotton, a first cousin of Janet’s mother.

Family and Friends

John and Janet settled in a new apartment overlooking Gramercy Park in New York, near the National Arts Club. Home life was happy, and to John and Janet’s great joy, their first child, Kate Kinley, was born in 1932. During the next two years, John was occupied with the National Arts Club, serving two terms as president. These would have been blissful times but for the Depression, which badly hurt many of his friends, especially those in the arts. John, who had wisely put aside “something for a rainy day,” was always there to help.

Throughout the late 1930s, John gave increasing responsibilities to his executives and spent more time with his family, which was augmented in 1935 by the birth of John Robert Gregg Jr. As a respite from their busy New York lifestyle and to give their children the benefit of the countryside, in 1937 the Greggs bought a Colonial-style house surrounded by unspoiled land in Wilton, Connecticut, which John named “The Ovals,” a reference to the curved lines Gregg Shorthand is based on.

As he gained more leisure time, John applied much of his energy to unobtrusive philanthropic work. He instituted scholarships for young people in several fields, and he supported the Mechanics‘ and Tradesmen’s School, which helped New York’s poor children and orphans.

Golden Jubilee

In 1938 John, Janet and the children sailed to England on the Queen Mary to attend a banquet in London marking the 50th anniversary—the Golden Jubilee—of Gregg Shorthand. More than 500 people were there, and the highlight of the evening was when John was presented a solid gold case decorated with the names of all the great shorthand inventors, beginning with Marcus Tullius Tiro and ending with John Robert Gregg. Inside the case was a duplicate of the Light-Line alphabet copyrighted on March 29, 1888, and an inscription addressed to: John Robert Gregg, Doctor of Commercial Science, Inventor, Educator, Author, Historian, Patron, and Lover of the Arts.

In the United States, the Golden Jubilee was celebrated at New York’s Commodore Hotel on Oct. 8, 1938. A succession of speakers paid tribute, and others not present sent equally glowing messages of good will. One of them came from Fulgencio Batista, “First Citizen of Cuba,” who sent an amethyst ring engraved with two names: Batista and Gregg. Batista had not forgotten that many years before, when he was a very poor young man, John had given him a free course in Gregg Shorthand.

Later Years

During World War II, John once again did volunteer work for both the Allied forces and British civilians— services that were acknowledged at the war’s end when King George VI awarded John the Medal for Service in the Cause of Freedom.

In his later years, John spent much of his time at “The Ovals,” but never stopped working. With Janet’s help, he continued to edit and write for his magazine and wrote a book titled, The Story of Shorthand.

On June 17, 1947, John celebrated his 80th birthday and received thousands of greetings from around the world. He had lunch with a group of friends at the Advertising Club in New York, then went home to his family. When a reporter asked him the secret of a long and happy life, he replied, “Be interested in everything and everybody.”

In December, John entered the hospital for a serious operation. He made a good recovery and soon resumed his writing. But just as he appeared to be regaining strength, he suffered a heart attack and died on February 23, 1948. Among the many tributes paid to him after his death, none was more fitting than one in the National Shorthand Reporter: “Mortal man does not possess a measuring device for the good that he accomplished on this earth. Generations yet unborn will profit from his busy life and accomplishments.” To benefit future generations more directly, John Gregg’s widow, Janet Gregg Howell, created a charitable foundation that, in 1985, became the John Robert Gregg Fund in The New York Community Trust.