A Lifelong Commitment to Culture, Community, and Giving

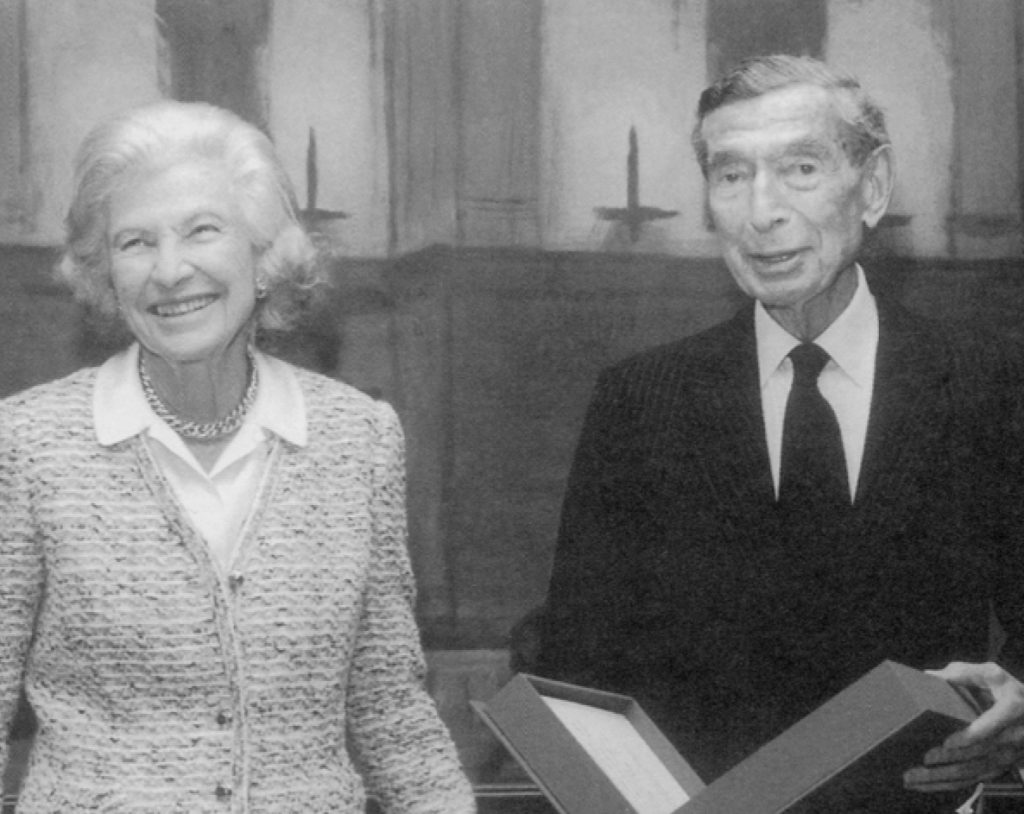

John Langeloth (1902-1996)

Frances “Peter” Lehman Loeb (1907-1996)

Memorialized by the John L. and Frances L. Loeb Fund in The New York Community Trust

Though undeniably born into luxury, John Langeloth Loeb was never one to coast. He steered his life with purpose and hard work, blessed with an uncanny instinct tailor-made for success in finance. He had the steady confidence of a man who knew his subject and his strengths. He was passionate about the arts, education, medicine, and politics, and used his considerable wealth to advance those causes.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1902, he was the second of four children born to Adeline Moses and Carl Morris Loeb. Their first son, they chose his middle name to honor Jacob Langeloth, the businessman who had launched Carl’s career and became a close family friend. Young John Langeloth would live up to his name. He would be instrumental in launching the second stage of his father’s career, this time in finance, establishing his own reputation in the process.’

Early Life

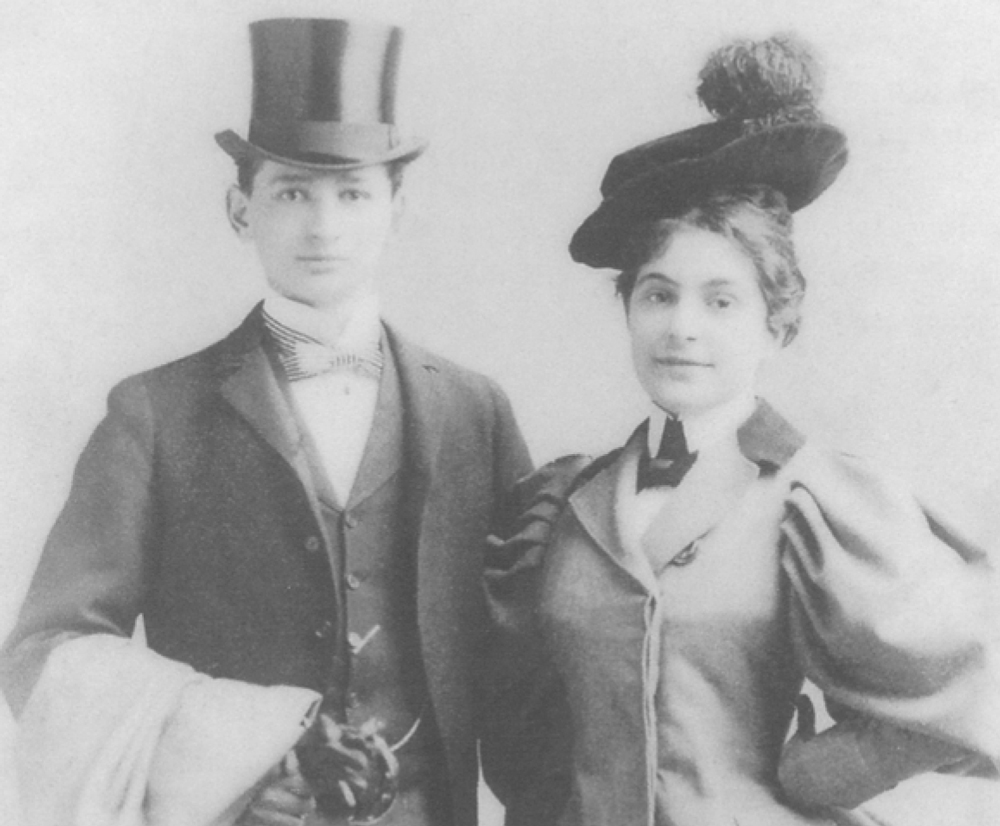

John’s father, Carl, was a German-Jewish immigrant who rose rapidly through the ranks at American Metal from “gofer” to president before he turned 40. Carl married Adeline Moses, descendant of a Jewish pre-Revolutionary War family. The young family moved from St. Louis to New York when John was three.

Their four children attended the progressive Horace Mann School. John played football, basketball, and baseball with his brothers, while his sister distinguished herself in basketball and tennis. When they were at home, the children spent most of their free time in the library. In the summer, they joined cousins and extended family at exclusive enclaves in the Adirondacks.

Their father, known by now as C.M. to most people, was a serious man. Their mother referred to him always as “Mr. Loeb,” unless she was angry, on which occasions she called him Carl. He had no time for frivolity or gossip and would have none of it in conversation at dinner. Instead, each night he led a weighty discussion with his children, the topics chosen (they later discovered) in alphabetical order from the encyclopedia.

Both of the parents were active philanthropists, leading by example, and generously supported hospitals, schools, and famously, the renovation of the Central Park Boathouse.

John attended Harvard, graduating cum laude in 1924. With no previous job experience, he wanted to test himself and learn the ropes before taking on a role with responsibility. So, rather than angling for a pleasant position at American Metal, he took a job loading zinc oxide cars at the company metal yard in Langeloth, Pennsylvania. Never before had he seen such different circumstances from his own. The experience became a touchstone for tolerance and compassion throughout his life. Quickly rising through the ranks, he was promoted to the New York office and returned home in 1926.

Marriage and a Young Family

Frances Lehman was the second daughter of Adele Lewisohn Lehman and Arthur Lehman, son of one of the original Lehman Brothers. When Frances was six months old, she became dangerously ill. At the same time, a new play, Peter Pan, had opened on Broadway. Her parents took to calling her Peter, the boy who lived forever. When she finally recovered, the name stuck. She was known as Peter until her death at the age of 89.

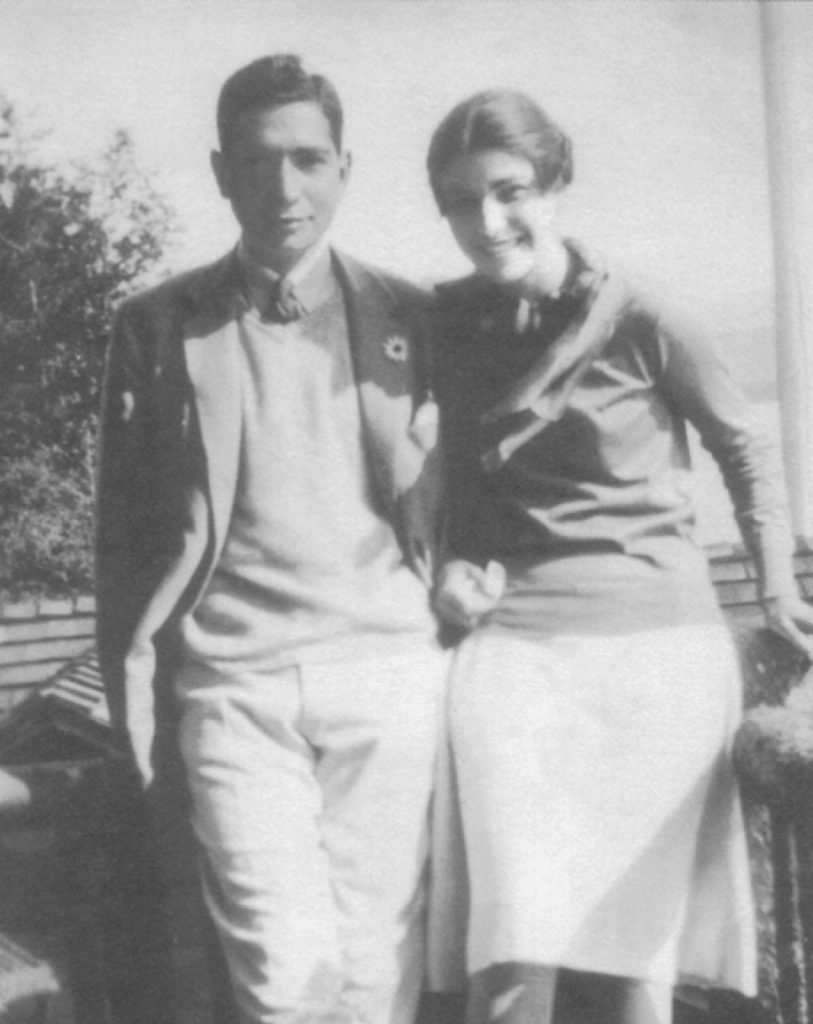

John and Peter first remember meeting briefly during a college football game when Peter was visiting Harvard. They didn’t develop an immediate connection, but their families were all part of “Our Crowd,” a nickname given to the tightly knit circle of German-Jewish elites in New York. Both fate and family kept throwing them together.

John was a guest at Peter’s debutante ball. When she became ill there, he drove her home. She was mortified that she had been sick in front of him and thought he wouldn’t want to see her again. But a few months later, she was invited to his birthday party. John and a friend were seated on either side of Peter. She was a tremendous beauty and both vied for her attention. John proved more interesting. Peter left with him for a night of dancing at some of the best speakeasies of the Roaring Twenties. Their romance began.

Not long afterward, they were being chauffeured through Central Park and, in an uncharacteristically indirect moment, John mentioned that he was thinking of going to Europe. Peter asked him when and John replied, “Whenever you’d like to go.” Luckily for him, she understood that he was trying to propose. On November 18, 1926, they married and embarked on the promised trip to Europe. Their fi rst child, Judy, was born the next year. John Jr. followed three years later and twins Arthur and Ann were born in 1932. Finally, Deborah arrived in 1946.

The Birth of a Business

Four years at American Metal had given John the business experience he was seeking but left him firmly convinced that his future did not lie in metals. He left for Wall Street and began work as a runner for Wertheim & Co. in 1929. There, he began trading his own funds, taking a $250,000 wedding present from his father and turning it into $750,000. In an early sign of the prescience that would serve him throughout his life, he sold his shares in March of 1929, months before the stock market crashed.

Meanwhile, his father, Carl, had left American Metal. With a comfortable fortune, he and Adeline took a trip around the world. When they returned, Adeline begged her son to do something to get her “caged lion” of a husband out of the house.

So, John approached his father with an idea. The stock market had hit bottom and John thought it was time to pursue finance in earnest. He proposed that they start a firm with his father at the helm. They set up shop in 1931 with secondhand desks and equipment from fi rms that had gone under in the crash. The timing couldn’t have been better. As the market began to rise again, Carl M. Loeb & Co. began to rise too.

The father-son pair began building their business, strategically absorbing other small outfits and acquiring the best people. The mergers culminated with the acquisition of Rhoades & Co. to form Carl M. Loeb, Rhoades & Co. in 1938. In less than eight years, the firm became a leading clearinghouse for New York Stock Exchange firms outside New York.

World War II

The company expanded overseas, doing the bulk of its business there. While visiting Germany, John became increasingly alarmed by the rise of Adolf Hitler. He decided that the situation called for decisive action. When his father refused to believe it, John persisted until Carl agreed to close the German office. Immediately, John called a company-wide meeting in France to provide an excuse for their employees to flee the Nazis. Much of the staff of Loeb, Rhoades served in WWII. John went to enlist and received a shock. He had been very ill a few years before, requiring an emergency operation. But he didn’t know the extent of the problem until he opened a letter addressed to Peter. It explained that he was unable to serve due to cancer. Peter had kept the true nature of the illness a secret from him in hopes he would recover sooner. The doctor said that the operation had removed the tumor but that they would have to wait fi ve years to be sure.

The Loebs did everything they could to help with the war effort, even moving the family to Washington, D.C. Peter became involved at the Red Cross. John used his experience at American Metal to serve in the Procurement Division of the Treasury, overseeing the production and distribution of supplies for the troops overseas.

After the war, the family moved back to New York; John returned to Loeb, Rhoades, and the company continued to flourish. In 1951, the firm moved to 42 Wall Street, giving them their first dedicated entrance on “The Street.” They had arrived. That same year, John became a governor on the New York Stock Exchange.

Then, in 1955, Carl died at the age of 80. John became a senior partner and presided over the firm’s continued rise.

The Business of Business

One of John’s legendary deals involved his acquisition in 1956 of Cuban Atlantic Sugar. He had become interested in the business while vacationing in Cuba. The Loebs found no anti-Semitism there: no country clubs barred Jewish members and Peter recalled for the first time socializing with the very top of society. No wonder it became a favorite haunt.

But the Loebs were also struck by the inequality in Cuba; small shacks stood in stark contrast to the gates of their country club. So in restructuring Cuban Atlantic Sugar, they established better working conditions for the 10,000 cane cutters hired during the harvest.

Fidel Castro was on the rise, and John, with his famous foresight, decided to get out of Cuba. He completed the sale of interests in the country just before Castro took power in 1959.

By 1963, Loeb, Rhoades had more than a thousand employees, correspondents in 140 cities, and was represented on the boards of many major corporations. The firm also developed the first money market fund and invented the mortgage-backed security. In 1974, John was named “Investment Banker of the Year” by Finance magazine.

A large part of John’s success was due to his ability to recognize and foster talent. Gene Woodfi n, a longtime partner at the fi rm said, “John was a terrific listener and cared not from where the oracle came.”

At the same time, John cultivated an imposing persona. Gene explained, “John happens to be a thoroughly likable man. But he likes to have the front of being very cold and very dignified and very tough. That is how he wanted the fi rm to appear and that’s the way we were.” The Bawl Street Journal, the annual parody of the Wall Street Journal, published an often-referenced cartoon: John is handing his coat to his butler while telling his wife, “No, I didn’t have a hard time at the office. But everyone else at Loeb, Rhoades did.”

Politics

John developed an early interest in politics, perhaps as a result of the rigorous dinner discussions of his youth. And as the niece of Herbert H. Lehman, the four-term New York governor and U.S. senator, Peter had politics in her blood. The couple frequently entertained mayors, senators, diplomats, and other public figures along with John’s business associates.

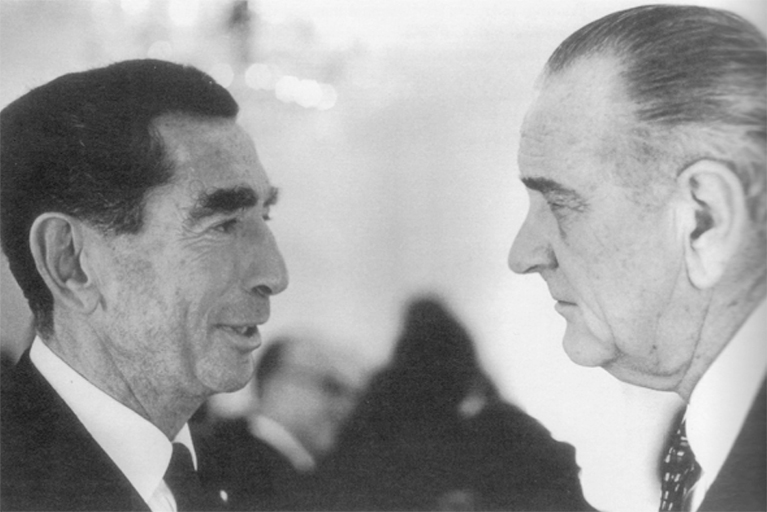

While Peter inherited staunch Republican views from her father, John often voted the Democratic ticket in presidential races. In fact, John took a few months off from his firm and became the driving force behind the Independent Committee for Johnson and Humphrey in 1964. The Loebs developed a friendship with Lyndon and Ladybird Johnson, vacationing with them at the Johnson ranch in Texas.

After the Johnson presidency, John raised money for Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and 1972. Here he got into a bit of hot water. The campaign fi nance rules were changed a month before John tried to avoid publicity by asking associates to donate with the understanding that he would repay them. He realized his mistake, immediately notifying the campaign to disclose the contribution and put everything back in line.

It was too late: John was charged with eight counts of illegal political contributions and faced eight years in jail and a substantial fine if convicted. But after the judge was inundated with letters about John’s character, patriotism, philanthropy, and the like, he canceled seven counts and treated the last as a misdemeanor, imposing only a nominal fine.

Peter was an active campaigner as well, almost always for the Republican ticket. She supported Eisenhower, John Lindsay for mayor of New York, and even Nixon’s presidential campaign, which placed her across the political aisle from her husband.

In 1965, Peter was asked to serve as the New York City Commissioner to the United Nations, a post she held for twelve years. Refusing any salary, she instead insisted that she have a sufficient budget and staff. Peter led the department well. Her jurisdiction expanded to include the entire diplomatic community in New York—more than 25,000 people.

Art and Philanthropy

The Loebs were passionate art collectors, favoring the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, including Picasso, Matisse, Renior, Manet, Gauguin, Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec, Monet, and van Gogh. They fi lled their Park Avenue apartment with art, opening their home to curators and art historians who would hold lectures there for students.

In 1961, Jackie Kennedy invited the Loebs to the White House on behalf of her fine arts committee. The Loebs agreed to underwrite the renovation of the Yellow Oval Room and were entrusted with overseeing the installation of a complete Louis XVI-era interior from furniture to art. After changing décor drastically with each administration, the Loebs’ interior remains a largely unchanged backdrop to private receptions for the world’s leaders.

The couple invested a great deal of time and resources in the study of the arts, funding significant projects at New York University, Vassar, and Harvard. John also became a life trustee of the Museum of Modern Art. A chairman of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, John eventually donated $10 million to the institute. He refused naming rights, insisting that the institute keep its name in perpetuity.

Reflecting on his support, he said, “I think of painting as silent poetry. A poem can speak to the inner heart, touch the springs of emotion, illuminate truths otherwise obscured—so can a great painting nourish the spirit and challenge the mind. The small part I have played in encouraging those who study the fine arts—and practice them—has enriched my life immeasurably. This is why I hope in years to come … they will think of me not as a patron of this institute, but as a grateful beneficiary of it and the world of art it serves.”

At Vassar, the Loebs funded a new art center. Their ongoing support would make Peter the largest donor in Vassar’s history. Initially, she didn’t want her name on the building, but when the president pointed out that no campus building bore a Jewish name, she reconsidered. The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center opened in 1993.

The Loebs also supported hospitals; because of his health, John always had a strong interest in medicine. He served on the boards of Montefiore and New York hospitals. They also supported an Arab community center in Israel after a visit in 1968.

In their memoir, the Loebs devote many pages to what they refer to as their “love affair with Harvard.” They supported a new theater, scholarships, and teaching fellowships to retain top talent. John was also elected as an overseer of the school and chaired various fundraising committees. After years of substantial donations, the Loebs made history with a gift of $70.5 million in 1995.

Peter passed away in May 1996. Not one to retire, John went to the office every day until just weeks before his death at the age of 94, five months after Peter.

The late Brendan Gill, a writer for The New Yorker, wrote, “If as St. Paul tells us, God loveth a cheerful giver, then John and Peter Loeb serve as models for the rest of us; they give as naturally as they breathe, and their benefactions are as varied as they are numerous.”

Members of the Loeb family were Trust donors over the years. In 2010, their children combined their funds and created the John L. and Frances L. Loeb Fund in memory of their parents.