Yale alum, investment banker, family man, and member of The Trust’s Distribution Committee—wrapped in an elfish sense of humor.

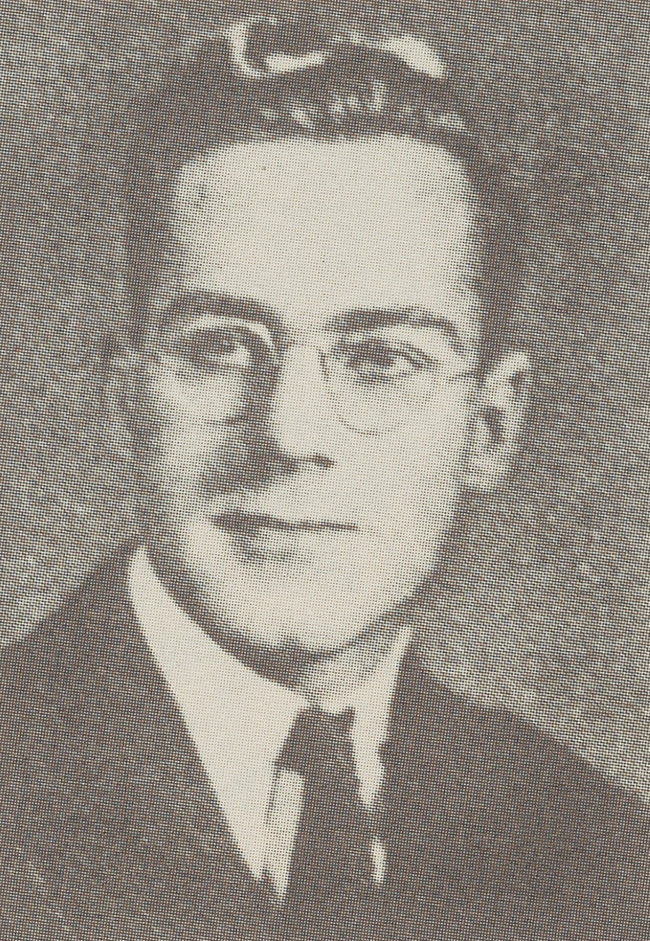

John Beckwith Madden (1919-1988)

John, Jake. Jack . . . John Beckwith Madden answered to all of them, each in a different part of his life. He was John in the business world, where, for 15 years, he was managing partner of the Wall Street banking firm of Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. He was Jake at Yale, his alma mater, where he was a dedicated trustee. And he was Jack in Brooklyn and Christmas Cove, Maine, where he lived.

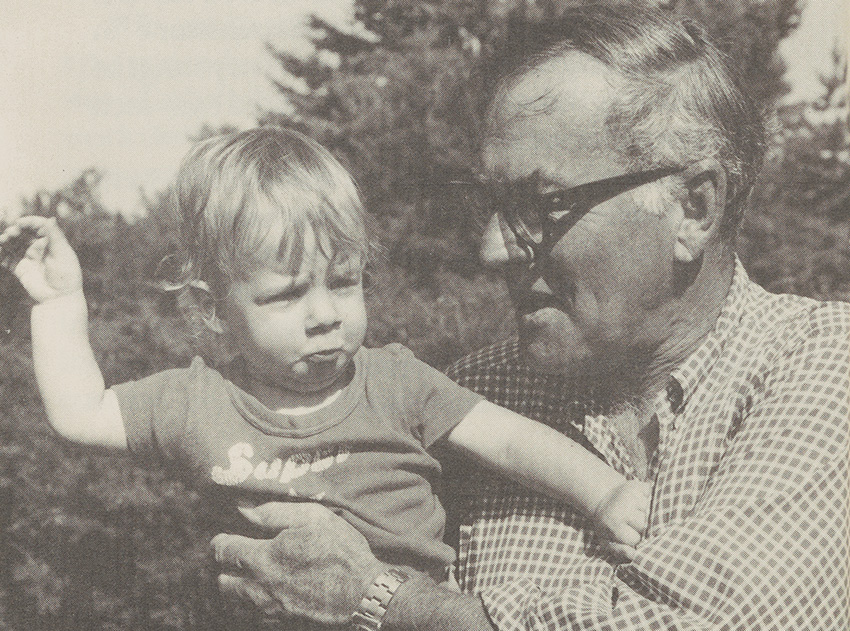

When he died at age 69, he was, somewhere at his core, still that youthful, innocent 10- or 11-year-old, a man who always carried with him, according to friends and family, “a bit of the boy.” It was evident in his most salient characteristic—his unparalleled sense of humor.

“He’d see humor in anything,” said his friend Stephen Heard. “He probably had the most insightful sense of humor of anyone I’ve ever known. Not in a cutting or hurtful sense, but in the broad-gauge, historical sense. He just had a way of using humor as a sword and a shield, in an uplifting, constructive way.” It was his passport to enjoying everything he did.

John Madden was born in Brooklyn on January 22, 1919, and, except for the years spent at Yale and in the Army, he never left. He was the son of John James Madden, M.D., and Rachel Beckwith Madden, and had one sister, Jean. Through 12th grade, he attended the Brooklyn Polytechnic Preparatory Country Day School—his sons would go there in later years, and his wife would become the first woman trustee. He graduated in spring 1937 and went on to Yale University that fall, majoring in American history.

The Renaissance Man

His ability to excel in many things was duly noted during his four years in New Haven. To Tim Ireland, a fellow member of Berkeley College, a residential college at Yale, and a partner of Brown Brothers Harriman & Company, it was a Horatio Alger story. “He was the Renaissance man,” he said. “He could do it all: scholar, athlete, nine-letter man, co-captain of the Yale 150-pound football team, all-American wrestler, and captain of the lacrosse team.”

In his junior year, Madden won a Phi Beta Kappa key and went on to be president of the society in his senior year. He received the coveted Alpheus Henry Snow Award as the most outstanding student in the senior class. According to the 1941 yearbook, Madden held scholarships in each of his four years at Yale. He was a member of the Pundits, the Fence Club, the Aurelian Honor Society and, in senior year, Skull and Bones, the Undergraduate Athletic Association and the Class Council.

After graduating from Yale in 1941, Madden enlisted in the Army. He rose to the rank of captain, serving in the field artillery during World War II in Hawaii, North Africa, and Italy.

Back in civilian life, he returned to Yale with the intention of going to law school. Once there, however, he realized the idea no longer appealed to him, so he decided to get a graduate degree in history.

That, too, was short-lived. Sitting at a carrel in the library a few months after classes started, he found his attention drawn to the street below. Life was passing by, it occurred to him, while nine stories up in the library, nothing was happening. So, he quit. This acceptance of a quick change of mind, even when one did not immediately appreciate the reasons behind it, enabled him to be more understanding of his children and other young people. He realized there wasn’t just one path to follow.

Career and Marriage

In March 1946, John Madden began his lifetime association with the private banking firm of Brown Brothers Harriman & Company. A year later, he met his future wife, Audrey Ritter. Although both were working at Brown Brothers Harriman, he in the credit department, she in the bond department, it took a course at New York University night school—Corporate Finance 201—to bring them together. He got his Master of Business Administration in 1949, she moved to another firm, but they stayed friends. Friendship led to romance, and they were married in 1950.

They settled in a small apartment in Clinton Hill, near Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, but when daughter Nancy was born, they moved to Brooklyn Heights. Eventually, they bought a beautiful brownstone on Columbia Heights that dated from the mid-19th century. Two sons, John Jr. and Peter, were born in 1954 and 1957, respectively.

Meanwhile, Madden’s career on Wall Street was moving right along. Nine years after joining Brown Brothers Harriman, he was made a general partner—at age 35, one of the youngest in the firm’s history.

“He was one of those people, very rare in this world, who have more than their share of common sense,” remembered Ireland, who joined the firm as a general partner in 1960. “He had all the intellectual powers in the world, but he never flaunted them. Never shot from the hip, never got excited. He was always very calm, very cool.”

If the business world brought out Madden’s dignified, serious side, his elfish sense of humor was never far below the surface. “I used to look forward to going to work,” Ireland said with a laugh, “and half the fun, all those years, was just being with Jake.” Though Madden had been advised by someone in the firm that ”John” was more appropriate in his position, when Ireland appeared on the scene, he resurrected “Jake” from their college days. The partners had become reacquainted when Madden and his wife began spending summers in Christmas Cove, Maine. The Irelands lived close by.

Christmas Cove

In Maine, the private John (there he was called Jack) Madden was almost a contradiction to the public, powerful New York figure. He was more open, more relaxed. “No venue or precinct was as fertile for Jack’s sense of humor as his beloved Christmas Cove,” Stephen Heard, another summer resident, recalled. With an assist from his theatrical makeup kits—he had two stashed in his bedroom closet—his imitation of Groucho Marx was classic. In his guise, showing up at some end-of-summer gathering, he would have people doubled up with laughter.

While the perpetrators of many pranks at Christmas Cove remain nameless, John Jr. remembers being hauled out of bed in the middle of the night from time to time to help his father with some nefarious scheme. The next morning, however, it was as if nothing had ever happened. The activities of the night before were never mentioned. “My mother would wink and let my father go make trouble,” said John Jr. Though never proven, evidence suggests she was a willing accomplice.

“He loved practical jokes,” said Audrey Madden. “He played many, and many were played upon him. The intrigue of them tickled everybody.”

The tables were turned on one occasion, when some much-disliked Maine road signs wound up in his briefcase as he and Stephen Heard were heading back to New York. Apparently, some of Madden’s heirs had taken them down during the night and, to dispose of them, stashed them in their father’s briefcase. Unaware of what he was carrying, Madden went through the security check at Portland airport only to set off the alarm system. Confronted with the metal signs, he explained, without blinking an eye, that he was going to have duplicates made in New York. With the explanation accepted, he was told merely to give them to the flight attendant while they were airborne. The only comment he made to Heard was, “I think some people might be in trouble next weekend.”

Rutherford’s Island—called Christmas Cove by the inhabitants—is a small, rugged island, about 400 acres in size, 60 miles northeast of Portland. It is connected to the mainland by a tiny bridge at the town of South Bristol. From the time their children were little, the Maddens had a summer cottage on the island. In 1973, they replaced it with a winterized home—a redwood structure pinned into a ledge, with a 270-degree view of the Atlantic Ocean, Damariscotta River, and Johns Bay. Madden also bought Outer Heron Island, a sanctuary for blue herons five miles out to sea, to keep it from falling into the hands of developers.

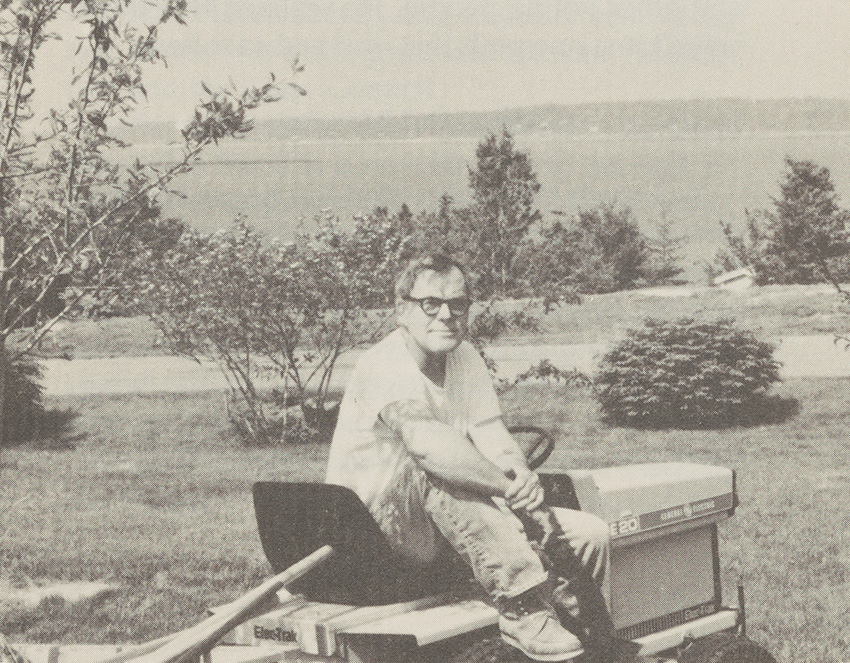

“He would go to Maine, and he would become a rugged individualist,” remembered Heard. “He would take off his coat and tie and step into his work clothes, and he would just absolutely revel in the earth and the sea.”

He derived enormous pleasure from his tractor and his chain saw. Many children at the Cove received tractor-driving lessons from Madden, including Heard’s two young daughters. One, a little redhead, was so small that Jack had to put a cushion on the seat and blocks on the pedals. Then he would walk along beside her as she drove around his lawn for an hour or more.

“They would come back so excited and elated,” recalled Heard. “Then, about half an hour later, two tractor licenses would appear on the dining room table. You never heard Jack come in. They would just be there, printed out on yellow paper, licenses for 6- and 7-year-olds.”

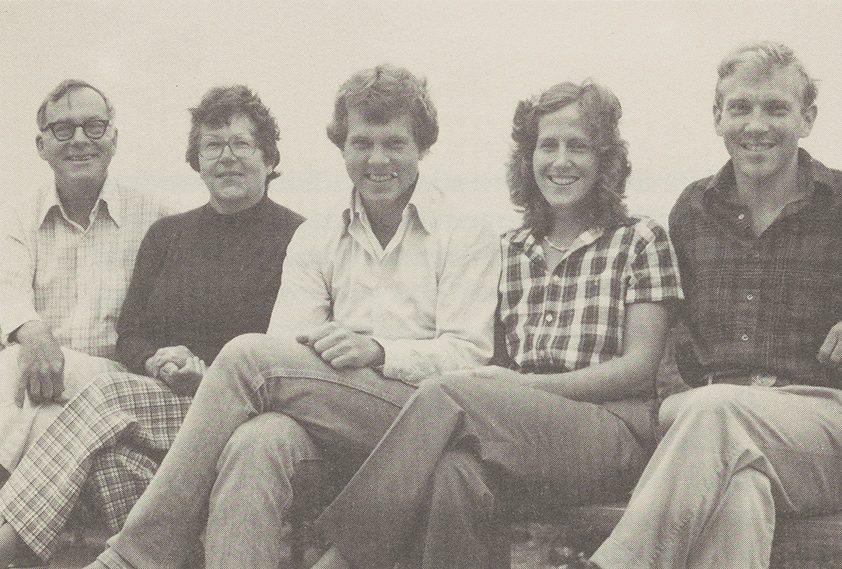

The Family Man

“Jack had a lot of fun,” said his wife, Audrey. “He enjoyed everything he did.” She remembered His relationship with his children as “lots of giggles.” At home in their brownstone in Brooklyn Heights, when the boys were young, he would carry them up to bed, one tossed over each shoulder like sacks of potatoes.

Madden was very close to his children, John Jr. remembered, but not in an intrusive way. “I think he realized everybody had to make their own decisions,” his son said. He didn’t dictate, but he was always there when advice was needed. “If he disagreed with something, he’d let you know, but he’d never forbid.”

His ability to give advice without it sounding like the only path open drew people to him, both from within and outside the family. Even those who had met him only once or twice would call him up and ask to come and talk with him. He was a good listener, and he had time for people and their problems.

“He was a very patient person, and a really good teacher,” said his daughter, Nancy. He stressed that the most important thing was to think things through, that there was always time and space to deal with a crisis.

Even at Brown Brothers Harriman, his secretary, Laura Kroemmelbein, recalled, “Nobody was ever afraid to talk to Mr. Madden.” He had a wonderful ability to handle people. When he had to call someone into his office to set them straight about something, the person didn’t leave feeling chastised, but rather that he or she had been helped.

“A Superb Managing Partner”

In 1968, John Madden became the managing partner of Brown Brothers Harriman, a position he held until he turned 65 in 1983. He remained a general partner until his death in 1988. In those years, he steered the firm and its partners through rapidly changing times in the financial world.

Ireland called it “an awesome task,” and added: “It would have been far easier to be the chairman and CEO of a corporation. To lead a partnership requires skill, patience, and wisdom. Jake had them all. He was a superb managing partner. He enjoyed it, and he was good at it.”

“He was a good financial man in all respects,” said Terry Farley, who was managing partner of the firm from 1984 to 1995. In the 1960s, when Brown Brothers Harriman began developing an investment banking function—advising clients and working with them on mergers and acquisitions—Madden was one of the guiding lights. Farley, as a younger partner, frequently sought Madden’s guidance. “He was an incredibly wise man,” he said, “and he never looked at things through his own ego.”

Madden was considered the architect of the restructured Brown Brothers Harriman & Company, linking the firm of the 1930s with a new generation of partners, and setting up a system of recycling the firm’s capital over generations, one of the most difficult things to accomplish in private business without any outside source of funds. With patience and a deft touch, he led the steering committee and, in due course, the whole partnership into agreeing to reduce the age at which older members become inactive, when the firm’s capital is gradually passed on to younger partners.

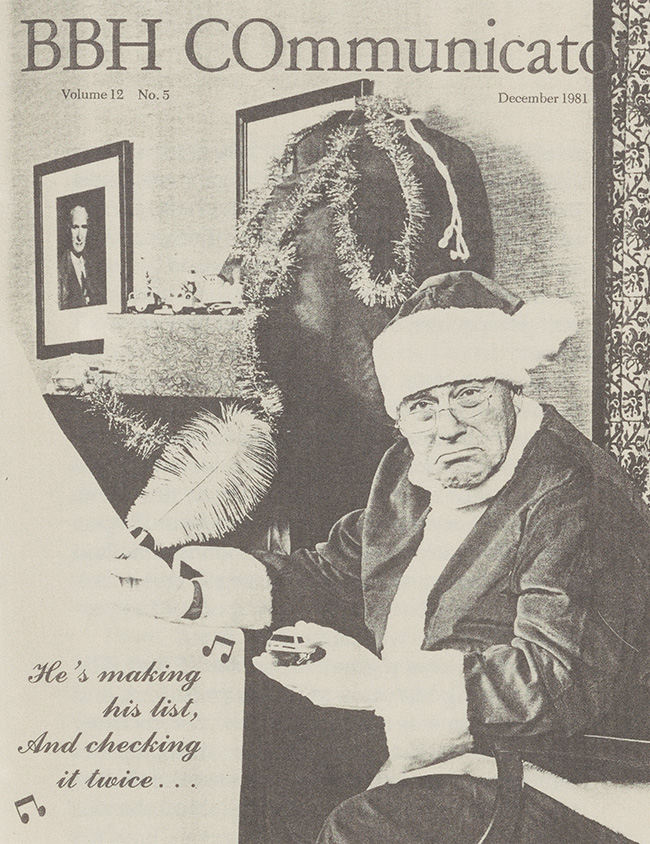

Madden was vastly amused when he found out, after some time, that partners and others at Brown Brother Harriman called him “old eagle eye” because he had a reputation for not letting anyone get away with anything. With his piercing eyes and his crusty visage, it was an apt nickname.

As his wife said, he was not “a grave person.” He even managed to bring his sense of theater into the serious world of banking when his priceless, grumpy Santa graced the cover of the winter 1981 issue of Brown Brothers Harriman’s magazine. The morning photo session had produced an endless array of cheery, chortling Santas when the photographer asked for one more shot. “Enough is enough,” said Madden firmly. “Time to get back to work.” And there it was—the “money” shot of a dour Santa peering intently over his glasses. It not only made the magazine, but matchbook covers as well.

Giving to Others

His friend A. Bartlett Giamatti, president of Yale University from 1978 to 1986, called Madden “a man for institutions—for those human creations that extend the individual into an idea, and give the idea a life far longer than any individual’s.” He was generous with his time to many voluntary institutions, aware of how much they need input from members of the community.

For more than 35 years, he was an active trustee of The Boys’ Club of New York, and at the time of his death was an honorary trustee. He was a member of the Distribution Committee of The New York Community Trust, a director of the James Foundation, and a member of the finance and investment committee of the Maine Community Foundation. He also was president of the board of trustees of Packer Collegiate Institute, chairman of the financial advisory committee of the Visiting Nurse Association of Brooklyn Inc., and a trustee of the Brooklyn Hospital.

Still, his greatest devotion, outside of family and career, was to his alma mater, Yale University, and he was a successor trustee from 1975 to 1987. At the time he came aboard, Yale had been through 10 years of difficult financial times, marked by unbalanced budgets and an endowment that was not generating the best possible return.

“Jake was, for a decade, really the central figure in bringing order to the chaos,” said Terry Holcombe, then vice president of Yale. During his tenure as chairman of the investment committee of the corporation, the endowment went from $500 million to $2 billion, performing better than any other endowment of a major university. At various times also chairman of the budget committee, Madden saw to it that the institution again operated with balanced budgets. According to William Brainard, then provost of Yale, Jake Madden cared deeply about the institution and its standards of excellence in education and scholarship. “Jake had a clear sense of the appropriate role of a trustee,” said Brainard. “While supportive of the best in Yale, he provided the right degree of discipline.” A steadying influence, not one impressed by some momentary crisis, “he was somebody who kept our perspective straight on what we were all about.”

Even at Yale, he could leaven a situation, particularly for recipients of notes he was known to pass at meetings. Holcombe remembered the little pieces of paper that, during intense conversations, would come down the row, handed from person to person. “You would open it to find some witticism or cartoon that he had drawn. It was always right on target, and it took the edge off whatever was going on at that particular time. He was famous for that.”

Madden was a great supporter of Bart Giamatti during his years as Yale’s president, and the devotion was returned in kind. “I remember the grin at some new instance of an ancient human foible; of how often he was the trustee other trustees turned to; of how generous he was in all things; of how funny he was—how his irony never intended to hurt, and how often his humor healed,” Giamatti said.

An Instinct to Connect

Madden had a special fondness for the Brooklyn Bridge, the connector of two mainstays of his world—his family and his work. On many days he walked across the bridge to work, using those minutes of solitude to put things together and plan his day. When the city closed the bridge’s walkway for repairs, the New York Post quoted an angry Jack Madden bemoaning, “Now I’m going to have to go down into the subways.”

He knew the bridge’s history and lore, and the stream of familiar faces he saw every morning. When it turned 100, he marked the occasion with a 13-gun salute fired by his own small cannon from the roof of his brownstone, which bordered the Brooklyn Heights promenade. Though the neighbors were thoroughly perturbed by the time the fourth shell had gone off, Madden remained unconcerned and completed the salute as planned, in proper military fashion. Not only did he love the bridge, but he loved the idea of the bridge because, as Giamatti said, “He was a bridge builder—among those he knew, between institutions, between his sense of the past and his sense for the present, between deeply rooted principles and the busy, practical daily world. His instinct was to connect. He never lost his bearings and, therefore, he became one of those by whom others could always find their way. He was the connecting center for so many of us.”

From March 1977 until he died in February 1988, Madden served as a member of the Distribution Committee of The New York Community Trust. His colleagues on the committee could always count on him for expert financial advice, and his interest in the grantmaking program was a factor when he set up a fund at the Trust in 1979.

After Jack Madden’s death of a heart attack on Feb. 9, 1988 at his home in Brooklyn Heights, his wife found the following, penned in his own hand, in the back of his datebook for 1988:

Ecclesiastes, chapter 9, verse 11: “I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill: but time and chance happeneth to them all.”

It summarized, she thought, his outlook on life — the poignant self-appraisal of a mature, modest, and very wise man.