From Bay Ridge to cotton miller.

Jean C. Caldwell (1878-1933)

For some men, the desire to succeed continues to drive them, even after success has been attained; for others, one success is enough to be enjoyed.

Jean C. Caldwell and Robert J. Caldwell were brothers and business partners with quite different goals and lifestyles. Both men were financially successful in their early years. Robert went on to achieve international distinctions that included membership in the French Legion of Honor. Jean Caldwell chose a life of quiet, comfortable retirement.

Both were the sons of John Armour Caldwell and his wife, Margaret, who came to the United States from Scotland in the mid-19th century. John Caldwell was a civil engineer who specialized in building water-supply systems, a profession that involved frequent moving from Mexico City, where he installed the water system, to Los Angeles, where he brought the water by pipeline from the Owens River Valley. Then the family moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where Robert was born. In 1878, Jean was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. And eventually the family moved to Brooklyn, New York. A third son, Armour, had been born in the meantime.

The family settled in the Bay Ridge section, a rural hamlet separated from the rest of Brooklyn by open fields and farmlands. Here, the Caldwell boys were educated. Robert received a degree from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. Jean also attended Brooklyn Polytechnic but did not graduate.

For some years, the brothers went their separate ways. Then, in 1910, with 16 years of business experience behind him, Robert established a cotton mill in Connecticut and persuaded his brother Jean to join him. Three years later, in 1913, the two men built a second mill at Danielson, in the eastern part of Connecticut, taking advantage of the waterpower provided by the Quinebaug River. The mills proved to be highly profitable ventures. Several others, in Connecticut and Canada, were built in quick succession. By the end of World War I, Robert and Jean were prosperous businessmen in their middle 40s. They now had time and money enough to follow their individual inclinations. Soon they separated again to live completely different lives.

For round-cheeked, dynamic Robert Caldwell, work was his avocation. He had always loved to travel, and, beginning in 1919, he spent more and more time in Europe, representing the United States as a special consultant in industrial and economic affairs, and as a guest of the French government in assisting in post-World War I rehabilitation. International relations involved him throughout the 1920s, and he was decorated with honorary orders awarded by grateful countries for his interest and contributions.

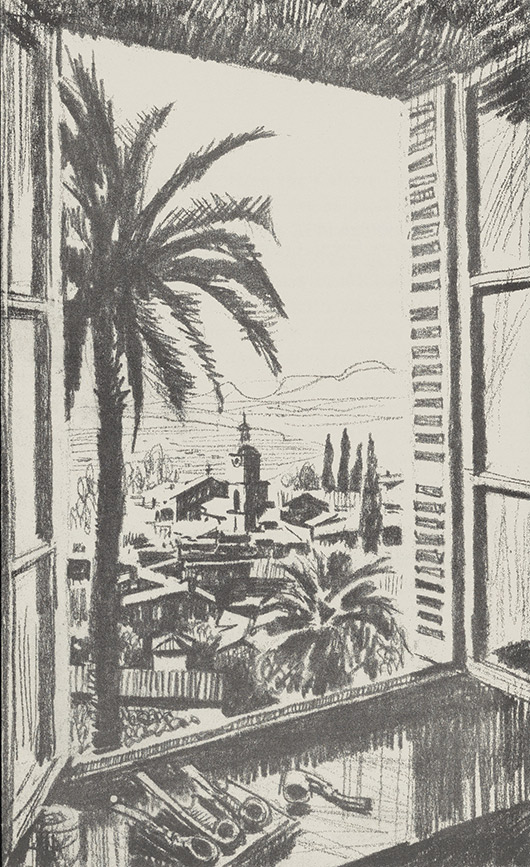

Easy-going Jean, usually seen with a pipe between his teeth, entertained no such interests. His ambition, according to family lore, had always been to retire as soon as practical from the hectic pressures of industry and commerce and to live a life of simplicity and ease. During the 1920s, Jean withdrew from active participation in his brother’s companies and became an expatriate, living in France. While his brother became well-known in the capitals of Europe, Jean lived quietly in a home on the Riviera.

The slow tempo of life, with the blue Mediterranean lapping the shores, suited Jean perfectly. He was entirely contented—or at least he thought he was. Then, somewhat to his own surprise, the middle-aged bachelor found his thoughts turning to romance. He had met the young and attractive Alice Jennings, and his determination for the single life weakened rapidly. They were married and were quite happy for a while. But old habits proved too difficult to break, and, after a few years, they parted amicably. Alice Caldwell moved to Paris and remarried. Jean had no regrets. In his typically affable live-and-let-live manner, Jean made provisions in his will for his former wife “in memory of the happy years we spent together.”

Alone again, Jean settled into his former routine and continued to enjoy the natural beauty of the Riviera. He was only 55 when he died there on Feb. 8, 1933. His will provided an income to his mother’s sister, Lillian Cook, until her death in 1947. And so that others might benefit for countless years to come, he requested that his estate then go to The New York Community Trust, to be administered for charitable purposes.