From farm boy to clothing delivery—by wheelbarrow!— business entrepreneur to leading New York Merchant.

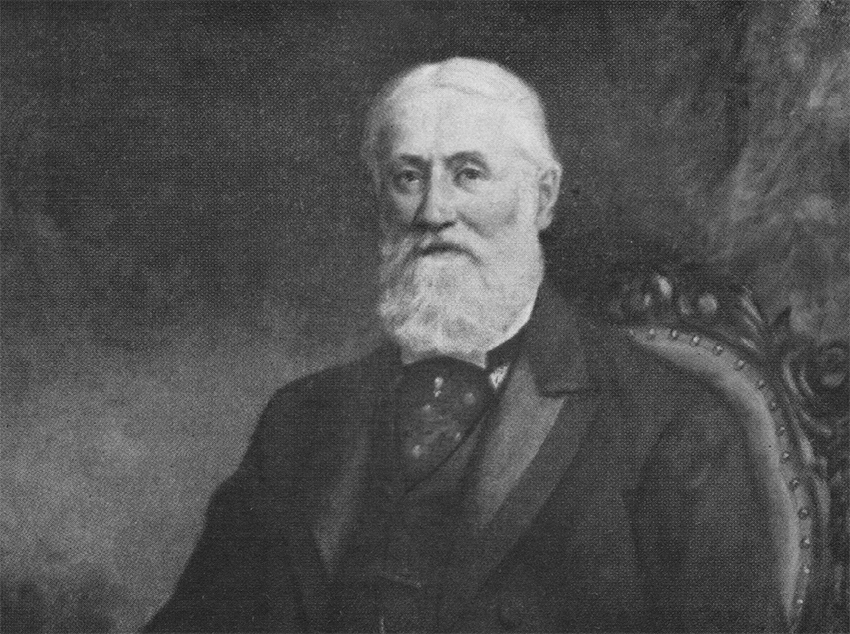

James Talcott (1835-1916) memorialized by his son J. Frederick Talcott (1866-1944)

When 18-year-old James Talcott arrived in 1850s New York, trundling a wheelbarrow of undergarment samples, the city was in the middle of a wealth and population explosion. Horses drew streetcars along the rattling rails of the lengthening streets. Tenements were rising to accommodate throngs of immigrants, and merchants in silk top hats were organizing the goods of the industrial revolution into empires.

Over the next 90 years, James, and later his oldest son, J. Frederick, would build a business through major epochs in New York’s history.

James Talcott was born in 1835 on a thousand-acre farm in West Hartford, Connecticut, the youngest son in a family that had arrived in the New World 200 years earlier.

The original Puritan spirit remained strong in the Talcott household. At a time when hard cider was deemed a suitable beverage at any time of day, James’ father never drank. His mother was born into a more gregarious family, and James ate well and ran free when he visited his maternal grandparents.

On the farm, however, he and his brothers rose before dawn to do chores and worshipped daily. One of James’ duties was to drive the family’s team of oxen loaded with wood to sell in Hartford, the big city to a farm boy. There, James lingered, excited by the bustle of commerce and the possibilities of making a profit. He began asking questions, aiming to learn as much as possible.

On the farm, however, he and his brothers rose before dawn to do chores and worshipped daily. One of James’ duties was to drive the family’s team of oxen loaded with wood to sell in Hartford, the big city to a farm boy. There, James lingered, excited by the bustle of commerce and the possibilities of making a profit. He began asking questions, aiming to learn as much as possible.

Unlike his older brothers, who studied at Yale, James attended Williston Seminary, eschewing the classical track and choosing instead the school’s shorter and more practical course of study. It turned out to be even shorter than he had anticipated.

Not long into his studies, James’ older brother John wrote a letter that would set the course of James’ life. John was running the New Britain Knitting Company and producing underwear to rival that of England, but he was losing money to dishonest middlemen. Would James leave school to serve as the mill’s selling agent in New York City?

And that is how, in 1854, James came to be pushing a wheelbarrow full of underwear through the streets of New York.

Despite the quality of his product, no businesses were buying. Surviving on apples for lunch, James finally found a shop that wanted to place an order—a large one. That night, he wrote in excitement to his brother with high praise for the shopkeepers. His brother extended credit on James’ recommendation and sent the order. Payment never came—the shopkeepers had gone bankrupt.

It was a major mistake, but an instructive one. Steadfast though devastated, James soon got a smaller order from another merchant. This time, he researched their creditworthiness thoroughly. They paid their bill and ordered again.

Out with his wheelbarrow to drum up more business, James overheard two merchants—who had just turned him down—laughing at his “fresh from the farm” looks. James immediately invested a good chunk of his savings in a frock coat and top hat, grew the beard he would wear until the end of his days, and hired another man to handle the wheelbarrow.

Within a year, James had increased the number of accounts and even won back business that New Britain had lost. It was the most profitable year the mill had ever seen.

Then the Panic of 1857 hit. Banks went under. Any merchant who was overextended failed. Factories closed or scaled back production. But under John’s steady management of the mill and James’ prudent sales operation, New Britain went on. James’ early lesson in the importance of solid credit was instrumental. It had fostered an iron-hard prudence that would steer him through many storms when others faltered.

The year after the panic, James was able to hire his first salesmen and began to take on merchandise of other factories in addition to New Britain. He had become an independent commission merchant.

New Family and the Civil War

The hardworking young man was largely oblivious to the growing social scene. Instead, James devoted himself to building his commission house. Fortunately, he still visited his family in West Hartford.

Through the past two centuries, the Talcotts shared farming and friendship with the Francis family. The Rev. Amzi Francis had left West Hartford for Long Island, but not before marrying James’ aunt. When the aunt died, Rev. Francis married again and had a daughter named Henrietta.

With his commission business gaining momentum, James began to turn his attention to the small and dark-eyed daughter. Like James, Henrietta was earnest and deeply religious, but she was warm where James could be fierce. They wed in 1861, when James was 26 and she was 18.

The newlyweds rented rooms in a family’s house across the street from the Astor Mansion, moving both literally and figuratively closer to fortune.

An excellent judge of character and events, Henrietta became a kind of silent business partner, the only person in whom James confided. She invested a good portion of her inheritance in the business. Her social skills would soon be essential in navigating their new circles.

The Civil War began the same year as the marriage. Factories couldn’t be built fast enough to keep up with the demand for cloth to outfit the Union Army. Many other commission merchants were stymied. But James, indefatigable as always, drew on his wide knowledge of mills, even ones farther afield in rural Massachusetts, and filled the orders. His business grew 16-fold in four years, and at the close of the war, he was a millionaire.

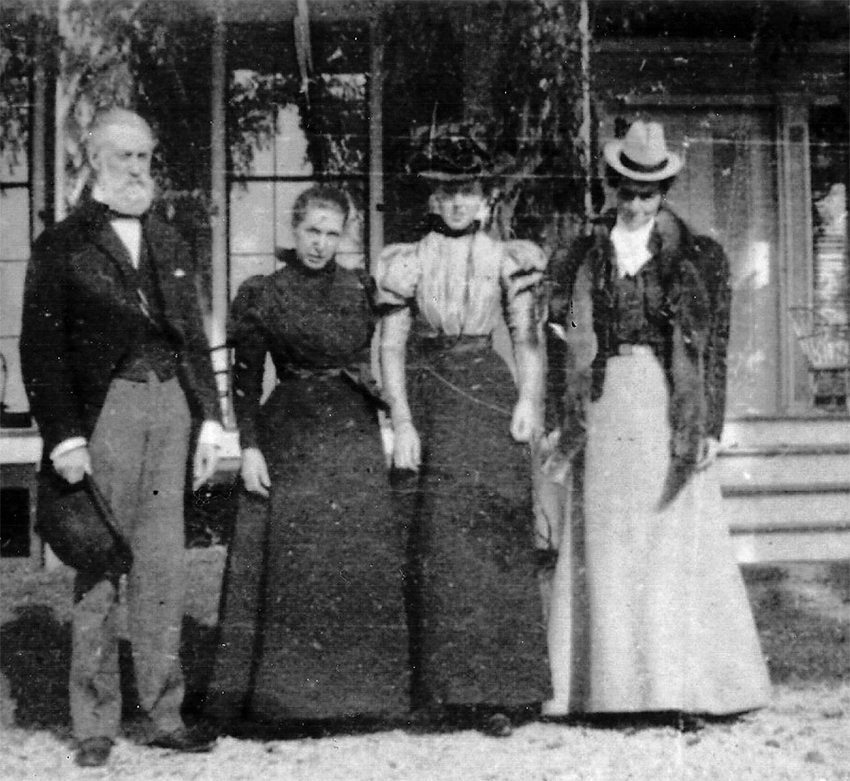

In 1864, James purchased his first home, a four-story brick affair on West 39th Street and Sixth Avenue, in a neighborhood just barely a decade old, with plenty of empty lots for new houses. James and Henrietta had their first son, J. Frederick, in 1866. He would be followed by Francis, Arthur, Grace and Edith.

A Steadily Growing Business

After the Civil War, get-rich-quick schemes filled the city, but James never swayed from his course. He came from a long line of successful farmers who, through caution and good sense, were able to turn a profit on their substantial harvests every year. This ancestry prepared him to be a careful and shrewd merchant of large quantities of cloth. He kept to his policies of prudence, hard work, and making loans rather than taking them out.

In 1868, he moved the business into two large, five-story buildings on Franklin Street, where it would remain for more than 40 years.

The buildings held a million-dollar inventory at all times, enabling James to fill orders anywhere in New York City in a few hours. Every major department store was a customer, including Wanamaker’s, Lord & Taylor, and Brooks Brothers.

In the evening, Henrietta would arrive at the office in the Talcott carriage, attended to by the requisite footmen and coachmen. But she would stop around the corner and walk to the front of the building to meet her husband. Picking him up in front would have been ostentatious.

Though James worked with many mills, he took a special interest in his brother’s. John had spun off the American Hosiery Company from New Britain, and James was a large stockholder and board member. He began to cultivate his eldest son, taking the young J. Frederick up to Connecticut for board meetings.

The Guiding Hand of Religion

By 1876, James and Henrietta had four children, and James began to look for a larger home. He took 10-year-old J. Frederick with him to survey the possibilities. Though James appeared to consult his son, asking him which house he preferred and why, J. Frederick knew it was more to understand his thinking than take his advice.

James selected a home on West 57th Street and Fifth Avenue, sharing the new residential neighborhood with Vanderbilts, Roosevelts, and the mayor of New York, just blocks from the newly completed Central Park. Like its new owners, the home was well appointed but not showy. Although the ceilings were so high that the servants used a special cane to reach the lamps, the frugal James was known to easily reach up and turn down the gaslights as he passed.

The daily routine included family prayer, grace at every meal, and bedtime prayers for the children. Missionaries were frequent guests, and their tales of far-off lands enchanted J. Frederick.

When he was 30, James was elected to the governing board of the influential Broadway Tabernacle—he was half the age of the other members. He was held in such esteem that little J. Frederick’s Sunday school teacher would refer him to his father for answers to probing questions.

James was deeply involved in mission work in the tenements. He taught Sunday school classes at the church’s mission there and supported the Home for Intemperate Men. In an effort widely covered in the papers, he was instrumental in building improved housing as an alternative to the notorious tenements.

Politics and “A Leading New York Merchant”

With the growing industrialization of the county and the advent of the railroads, factoring began to shift. No longer did factors need to handle the merchandise themselves but were relied upon more than ever to handle payment and billing on the mills’ behalf. The shift was tailor-made for James. His ability to discern creditworthiness became legendary.

In 1875, James was elected to the board of the Bank of Manhattan Company. The board chairman called him “a man of unblemished honor and integrity.” He also served as the vice president of the Chamber of Commerce. By 1891, James was in his 50s and a multimillionaire.

An ardent Republican since the birth of the party, James was active in the New York political scene. He took off every Election Day. After voting himself, he would visit the jails one by one, bailing out any Republicans who had been challenged at the polls and locked up by corrupt Tammany Hall forces.

He was floated as a candidate for mayor in 1890, but declined. Although he often was quoted in the newspaper, it was almost always as “a leading New York merchant,” rarely by name.

Through the market panics and two depressions in the years from 1857 to 1907, James landed in better financial shape than before. Speculation was against his nature, and though he drove a hard bargain, he was fair in his dealings. His style was slow, steady, and always prepared for inevitable disaster.

Since James was in a strong position after panics, he was able to purchase at the bottom of the market. In the depths of the panic of 1907, he arrived on Wall Street in a silk top hat and frock coat, by then a long-outmoded look. He carried with him a long list of securities and a pencil. When the market went up, the 72-year-old’s fortunes were greatly increased.

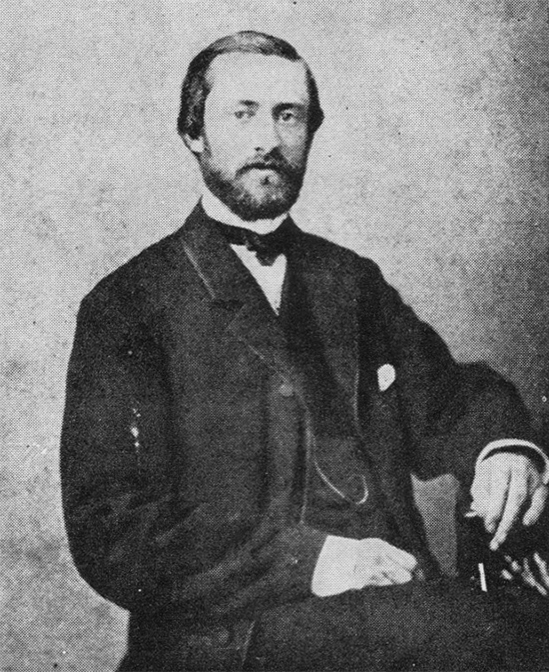

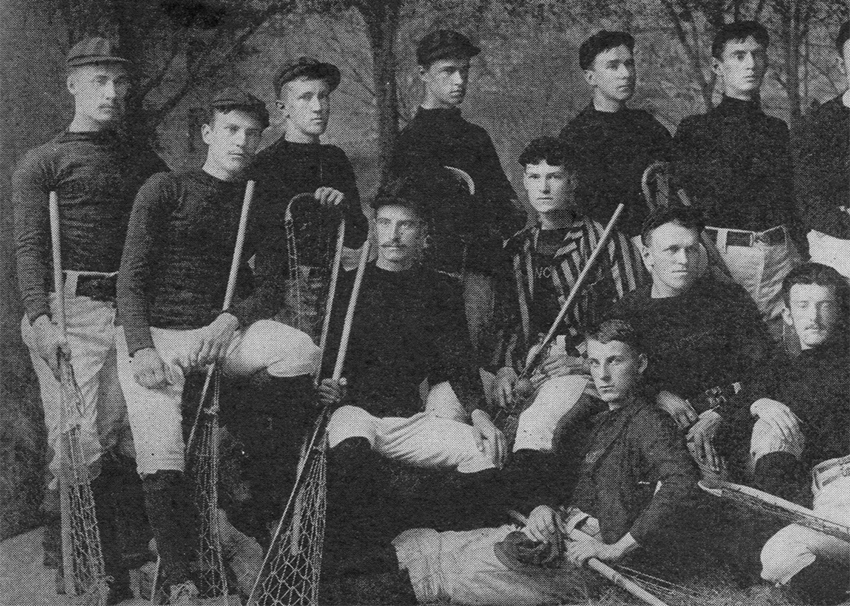

Frederick Grows Up

James and J. Frederick were worlds apart in disposition but remained close, nonetheless. The father was stern in demeanor and Puritan in his hobbies, while the son loved society, sports, philosophy, and the arts.

Sent to Princeton to study, J. Frederick immersed himself in education and athletics, and developed a large circle of friends. He earned a bachelor’s degree in 1888.

At the family summer home in Rumson, New Jersey, a fashionable summer retreat that attracted New York’s financiers, J. Frederick became enamored of a young woman from a neighboring house.

She was Frank Vanderbilt Crawford, named after her mother, whose father had made a promise to name his first child after a dear friend and kept his word even though the child was a girl. The younger Frank and J. Frederick were engaged in 1889 and married the next year in a wedding the New York Times called “unusually brilliant.”

After earning his master’s from Princeton in 1890, J. Frederick was still drawn to academia. He traveled with his new wife to England, where he studied theology at Oxford and avidly attended religious debating events and sermons.

From England, the young couple took tours of Egypt and Palestine, and then embarked on an impromptu 11-day horseback caravan into Syria. So began a lifetime of world travels. Returning to Europe, the couple spent another year in Berlin, where J. Frederick continued to study.

Back in New York, J. Frederick enrolled in the Union Theological Seminary. His parents feared he was in a bed of heretical teaching, but it made sense to J. Frederick. Always an independent thinker, he had never been impressed with Sunday school, and never sent his own children. He preferred to instruct them on a rolling scroll contraption of his own making that covered the Bible from creation to Revelations. He left Presbyterianism to become an Episcopalian and was ordained a minister in 1893.

That same year, J. Frederick bought a house in one of the northernmost residential parts of the city—on West 87th Street—less than a block from Central Park. J. Frederick and Frank’s four children were born there.

Frederick Enters the Business

Like his father, J. Frederick was involved in mission work in the tenements. After being ordained, he took a position at St. Bartholomew’s, where he set up an employment bureau for the church’s mission. His five-year tenure was a great success, sparking an interest in business.

In 1897, J. Frederick joined his father’s business full time, also becoming a director of the American Hosiery Company.

It was the turn of the century, and factoring was changing again. Ledger books gave way to adding machines, the telephone was become a fixture in business, electric lights outstripped gas lamps, and top hats and frock coats were set aside for business suits (except for James).

James put J. Frederick in charge of shifting the staff and the business to match the shifting times. The company drafted what would become the Factors Lien Act, which laid the groundwork for the growth in the factoring business. As a result, factoring drew even closer to banking, no longer handling merchandise and instead providing capital loans to the mills and factories.

A venerable man of 76, James was the last to leave in the evenings. After more than 40 years of business on Franklin Street, Talcott moved his business to Fourth Avenue, near Union Square. That day, he sat in his customary place next to the second-floor window, surveying the move and the street below.

WWI and Years of Change

J. Frederick’s wife, Frank, fell ill in 1914 at the start of World War I. She died in March 1915. Their sons were at Harvard, but their daughters were still in high school. J. Frederick came home for lunch each day to spend time with them.

In 1915, the business incorporated to better represent its various interests and became James Talcott Inc.

Having lived through the losses during five years of civil war, James was a staunch peace advocate. In the 1890s, he went on record at the Chamber of Commerce against the Spanish-American War. During World War I, he was a frequent speaker at the anti-war community of Lake Mohonk. But James wouldn’t see the war’s end. He passed away peacefully in 1916, surrounded by family and friends. He was 86.

In 1917, J. Frederick married Louise Simmons, daughter of Florida orange orchard owners, in a small ceremony.

Frederick at the Helm

After James died, J. Frederick took on the full responsibilities of the business. Following his father’s example, he sought the counsel of him mother, Henrietta, who was invaluable during the transition.

At the end of World War I, J. Frederick’s sons returned from the Navy, and he brought them on in 1918, giving a principal role to his eldest son.

Frederick saw firsthand how the business was able to weather the panic of 1907 and the disruption of WWI, largely because the company didn’t owe money to the banks. So, like his father before him, J. Frederick didn’t speculate during the boom of the ’20s. James Talcott Inc. simply expanded sales and made more loans.

From 1926 to 1928, sales doubled, from $17 million to $34 million. Even the Great Depression caused only a dent in profits. By 1941, sales had increased to $103 million.

New York continued to change. J. Frederick held out on the automobile until his teenage children were invited to a dance 15 miles away, an impossible journey for a horse to make in a day.

The subways tunneled under the city and the Statue of Liberty raised her torch at the mouth of the East River. The palatial Grand Central Terminal, Penn Station, and the New York Public Library on 42nd Street rose in tandem.

As a director of the Chatham and Phoenix National Bank, J. Frederick was involved in the construction of the Empire State Building.

Throughout the tumult of those years, J. Frederick cultivated a love of trout fishing, never missing a date in late April when the ice broke on the lakes and streams of the Adirondacks. He purchased a camp on Lake Bisby, and often would invite one or another of his daughters or grandchildren up to enjoy the air.

In February 1944, at age 78, shortly after publishing his memoirs, J. Frederick passed away at home.

The Talcott Legacy

Throughout his career, James Talcott gave at least 10 percent of his income to charity. In addition to his mission work, he funded an arboretum at Mount Holyoke, a library in West Hartford, a women’s dormitory at Oberlin College, and a hospital in China. James was a founder and trustee of Northfield Seminary in Massachusetts, and he and Henrietta funded a professorship for religious instruction at Barnard College, where she was a trustee. Henrietta also was a founder of the YWCA while James sat on the international committee of the YMCA.

At James’ death, Henrietta funded a building to house the New York Bible Society in honor of her late husband. The building was demolished in 2015, and an apartment complex was built on that site.

Frederick carried on his father’s commitment to philanthropy. In addition to his support of the missions, he helped raise $500,000 for Lincoln University, a historically Black university in Pennsylvania. He also was a longtime supporter of a Black trade school in the South.

Frederick was president of the American Bible Society and national chairman of the Boy Rangers. He expressed his love for the arts as a trustee of the Manhattan School of Music and as president of the National Arts Club, where he championed women as equal members and started a junior division to make the club more affordable.

Frederick realized a goal of his father by founding the James Talcott Fund, a private foundation, to honor his father and involve his children and relatives to inspire a family of philanthropists. A number of years ago, the family terminated the foundation and, with the assets, established a fund in The New York Community Trust. Talcott descendants still carry on the legacy of James and J. Frederick.