In 1924, the Jacob H. Schiff Memorial was established by Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her father, to be administered by The New York Community Trust for charitable purposes.

Jacob H. Schiff (1847-1920)

To the tranquility of his summer garden, Jacob H. Schiff retired each morning to begin the day with his devotional prayers. He was not a tall man, but his bearing was so erect that he gave an impression of height. Alert blue eyes, white beard neatly trimmed, broad linen necktie, and the ever-present rose in his buttonhole enhanced the portrait of an aristocratic gentleman. When his prayers were finished, Jacob completed his morning ritual: He picked a single perfect rose for his wife, Therese, and returned to the house to present it to her. In good weather, he commuted daily by boat from his summer home near the Atlantic Highlands in New Jersey to his Wall Street office in New York.

“On the mountaintop, all paths unite” was a favorite saying of Jacob Schiff, a veritable Everest of a man of his time in whom the well-known paths of philanthropist, banker, and humanitarian came to meet with the private paths of the man in the garden—loyal husband, loving father, and devoutly religious Jew.

Jacob Henry Schiff was born on January 10, 1847, in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany. The Schiff family tree shows one of the longest continuous records of any Jewish family, dating back to the 14th century in Frankfurt, and from there back to biblical times. It was a deeply religious and highly intellectual family that numbered among its members bankers and businessmen, scholars and rabbis. Jacob’s father was a successful stockbroker, and Jacob was the second son in a family that included four boys and a girl.

When Jacob was 16, he left school and went to work for his father. But Jacob, a serious, well-disciplined boy, did not get on well with his father, and after two years he decided to leave Germany. With $500 in savings, Jacob went first to England and then to America. He arrived in New York in August 1865 and immediately contacted some former residents of Frankfurt who were active on Wall Street. In less than a year and a half, he formed his own brokerage firm with two other young men. It was just a few days before his 20th birthday, and he was not yet of a legal age to sign the partnership papers.

But Jacob was not happy working in this partnership. The firm dissolved, and Jacob returned to Germany, where he worked for a time as the manager of a bank. This proved not to be the proper atmosphere for the brilliant and dynamic young man. His mother, to whom he had always been very close, believed his future lay in the United States, and she urged him to return. “You are made for America,” she told him.

And so, in 1873, at age 26, Jacob arrived in America a second time and joined the investment banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb and Co. as a junior partner. Jacob soon became interested in the investment possibilities of railroads, expressing a tireless interest that embraced virtually every aspect of this growing industry. Soon his expertise began to pay off handsomely for Jacob Schiff and for Kuhn, Loeb.

The founder and senior partner of the firm, Solomon Loeb, was 18 years older than Jacob. His wife, Betty, was a warmly hospitable person who seemed happiest when she was entertaining guests at her sumptuous Sunday night dinners. She took an immediate liking to her husband’s young partner, and Jacob became a frequent visitor at the Loeb house. Betty Loeb was soon convinced that Jacob Schiff would make an excellent husband for shy, petite Therese, the eldest of the five Loeb children.

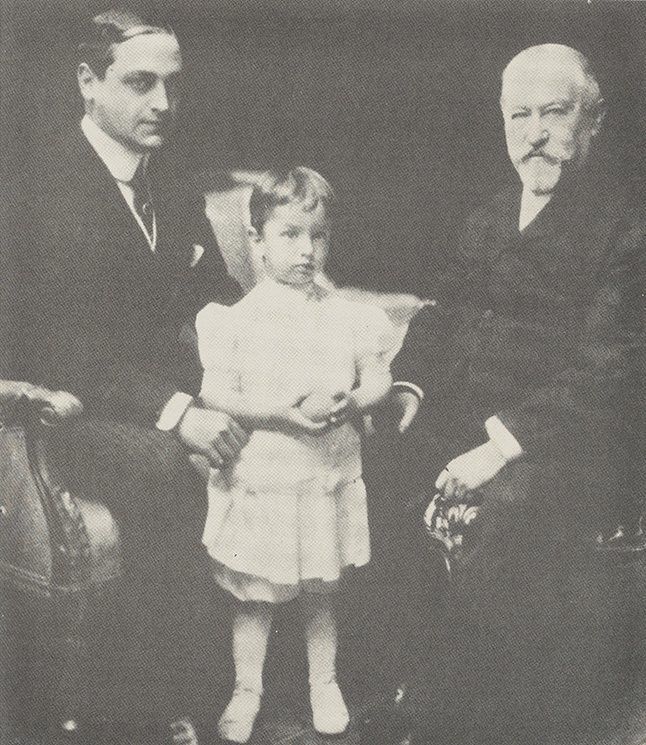

Her conviction was correct, and Jacob and Therese were married on May 6, 1875. There were two wedding presents from the bride’s parents: a large brownstone on 53rd Street and Park Avenue, and a full partnership in Kuhn, Loeb and Co. Within two years, the union had two children, Frieda and Mortimer. The latter was always called Morti.

The Schiffs‘ marriage, their daughter wrote many years later, was “an example of harmony and understanding. They were seldom apart during the 45 years of their life together, but during their rare separations, they wrote to each other daily.” Jacob was devoted to his shy, retiring wife and proud of her gentle beauty, and with rare exception she deferred to her husband’s judgment.

One of those rare exceptions had to do with where the family was to live. When the young Schiffs outgrew their first home, they moved to another house on West 57th Street. Then Jacob bought property on Riverside Drive and 72nd Street, where he intended to build. Therese was broken hearted. Social life among young matrons of the 1870s was a highly formalized ritual of visiting and leaving calling cards. Tuesday was established as Therese’s day “at home” when friends came to call, and she feared it would all end if she were removed to such a remote area as the west side of Manhattan. She wept; Jacob relented. In 1885, they compromised and moved to a house on upper Fifth Avenue, particularly remarkable for the fact that it was 25 feet wide and 150 feet long. Therese would have preferred a square house, but she was too pleased with the location to object.

Generally, the Schiff family lived a quiet, well-ordered life that suited a person of Jacob’s disciplined temperament. Jacob was a devout man, and religious observance was an integral part of his life. As a young man he had composed his own grace, which he recited after meals. Friday evenings were reserved for the family. These dinners were particularly lavish, and everyone dressed in their best clothes. On Wednesday evenings, the family occupied a seasonal box at the Metropolitan Opera.

Jacob was a physically well-coordinated man who believed in the benefits of exercise. He walked three miles downtown every morning. At the end of his walk, he was met by a chauffeur or took a trolley to ride the rest of the way to his office. He had a bowling alley built in the basement of his house, and each evening after the 6:30 family dinner, he invited the children to join him for a game. The children didn’t care much for bowling, but Jacob Schiff was not the sort of man one refused easily.

Winters were spent in the long, narrow house on Fifth Avenue. On alternate summers, the family went abroad, always including visits to relatives in Germany in the itinerary. Stay-at-home summers were divided: June, July, and September were spent at the house in Sea Bright on the Jersey Shore. There, Jacob always took a bicycle ride between teatime and dinner. The dog days of August were spent in Bar Harbor, Maine.

The summer after Frieda’s 18th birthday in 1894 was a European summer. During the family’s sojourn, the young woman was introduced to Felix Warburg, a popular young bachelor who took an immediate and strong liking to Frieda. After their first meeting in Frankfurt, Felix had a way of turning up unexpectedly, much to Jacob’s displeasure, at various places the Schiffs were stopping. But Jacob was not prepared to lose his daughter so easily. When the Schiffs and the Warburgs met in Brussels before the Schiffs’ return to the United States, it was decided that Felix and Frieda were not allowed to correspond directly, but they could write to each other’s parents. With that clearly understood, the couple parted. But love eventually conquered. Six months later, Felix arrived in New York and went to work at Kuhn, Loeb. On March 19, 1895, Felix and Frieda married.

As for Morti, it was assumed from his early years that he would train for a business career. He attended Amherst College but withdrew before graduation to become a partner in Kuhn, Loeb. He later married Adele Neudstadt, and his father presented them with the long, narrow house on Fifth Avenue. Jacob bought another house a few blocks away. Therese at last had a square house, as she had always wanted.

While his children were growing up and falling in love, Jacob Schiff was soaring to the heights of a brilliant career. Early in the 1880s, Solomon Loeb, who had built his business reputation on a conservative financial philosophy, began to withdraw from the business in favor of his bold, innovative son- in-law. In 1885, Loeb retired, leaving Jacob, then 38, as head of the firm. Within two decades, his reputation as a financial genius was international. Honors were being heaped upon him, from London to Tokyo. One of his close friends and associates was Sir Ernest Cassel, a leading London banker and financial advisor to the king of England.

In the decade before the turn of the century, railroading was probably the most important industry on the American investment scene. Kuhn, Loeb was the railroad industry’s most important investment banker. Schiff’s name became identified with most of the great railroads of the country—the Pennsylvania, the Great Northern, the Illinois Central, the Union Pacific. He offered not only the financial resources of his firm, combined with his own genius for problem-solving, but he offered something more: genuine concern. With such powerful men of railroading as James Hill and E.H. Harriman, Schiff was not only a business associate but also a friend. Perhaps most revealing of the great respect held for him is that others observed he was the only man whom the financial titan J.P. Morgan ever recognized as an equal.

Although Jacob Schiff’s name is most associated with railroad financing, his interests and activities reached out in many directions. Mining was an important investment, perhaps second to railroading at that time, and Schiff was involved in that industry. He also had interests in meat packing and in insurance. And he helped the New York rapid transit system, then in its infancy, to grow rapidly.

Inevitably, Schiff’s name came to be associated with New York politics. In 1903 he was asked to run as alderman, but he declined because of a hearing impairment. This did not prevent his name from being mentioned the following year as a possible mayoral candidate. Throughout his career, he showed a strong interest in all aspects of good government, from the administration of the police department to keeping the city streets clean.

When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, Schiff already had become infuriated with the czarist regime in Russia because of its anti-Semitic pogroms. Through his company, he floated a loan to Japan. After the conflict, the emperor invited Schiff to receive one of Japan’s highest honors, the rarely bestowed Order of the Rising Sun. Schiff made the trip with a large entourage of relatives, friends, and servants, and met in privileged private audience with the emperor.

While in Japan, Schiff was called upon by Baron Takahashi, who was then the finance minister and later became premier of Japan. The baron’s 15-year-old daughter, Wakiko, came along and, to make polite conversation, Schiff said to her, “How would you like to go to America some day?” Apparently “some day” has a rather different meaning in Japanese, and the very next day the flabbergasted Schiff was informed that Wakiko could indeed return to America with the Schiff family, but that she would be permitted to stay “only two years.” In fact she stayed with the Schiffs for three years before she returned again to her homeland. For weeks after Wakiko’s departure, the Schiffs found affectionate little notes from her hidden behind pictures and sofa cushions.

During one of the summers in Germany, when the Schiff children were still quite young, Jacob began to give each of them an allowance of 50 pfenning a week—12 1/2 cents in American money. When they returned home, Frieda and Morti were required to keep track of which were the 12-cent weeks, and which were the 13-cent weeks. In addition, the Schiff children had to set aside a tenth of their “income” for charity—the Fresh Air Fund.

Jacob Schiff’s training of his children reflected his own belief that tithing was a religious duty. He insisted that only what he gave above this basic one-tenth could rightly be called philanthropy. Once, when someone congratulated him on a large gift, he replied, “That wasn’t my money I gave away.” His money was what remained after the obligatory 10 percent had been disbursed.

Furthermore, Schiff believed in the ancient Talmudic rule that “twice blessed is he who gives in secret.” As a result, no one ever knew just how much Jacob Schiff gave away during his lifetime. He had donated at least eight buildings, mostly to educational institutions, and it is typical of the man that he permitted his name to be attached to only one: the Schiff Pavilion of Montefiore Hospital.

Montefiore was one of the many charitable projects Schiff took an active interest in. He was among those who, in 1884, had conceived the plan for a hospital for Jewish “incurables.” Until his retirement from the board of directors in 1919, Jacob Schiff called on patients in the hospital every Sunday morning. He concerned himself with every aspect of the administration, and it was at his behest that the hospital’s function was broadened beyond its original intent.

Jacob Schiff was a man concerned with helping others on any scale, large or small. He often bought small businesses for promising immigrants: a barbershop for a man who had cut hair in Europe, for example. In 1906, he helped form the American Jewish Committee to protect the civil and religious rights of Jews and to better their lot wherever they were in the world. In 1914, he was among the founders of the Joint Distribution Committee, making funds available to enable Jews to live wherever they chose—either stay where they were or emigrate.

It appears Schiff originated the incentive gift. In 1911, he promised his daughter he would contribute $25,000 to the YMHA fund drive, of which she was chairman, if she could raise $200,000 from other sources by January. But as the New Year arrived, a frantic Frieda was still $18,000 short of the goal, and she knew her father always kept his word. Then a letter arrived, addressed simply to the chairman, advising that Mrs. Jacob Schiff had decided to make a donation in memory of her brother. The check was in the amount of $18,000. Frieda wrote later, “It was so absolutely characteristic of him, a man of his word, but his heart got around his word, and made it all legal.”

Early in 1920, Schiff’s health began to fail, but he refused to acknowledge his illness and insisted on keeping up his normal routine. It was an “at home” summer, and in September the Schiffs went to their Rumson Road home in Sea Bright, New Jersey, as usual. Despite the protests of his family, Jacob insisted on observing the Yom Kippur fast, although he was by then obviously very weak. On September 23, Schiff told his family he wanted to go back to their home in New York. Two days later, on the Sabbath evening of September 25, 1920, Jacob H. Schiff died. He was 73.

In his lifetime, Jacob Schiff had touched the lives of innumerable people, rich and poor, powerful and weak, famous and unknown. Thousands of these people, touched by a personal sense of loss, thronged his funeral to say goodbye to the great man who had been their friend, the mountaintop in whom all paths had united for the cause of good.