The Trust’s long-time leader wanted to “help make the world a little better”.

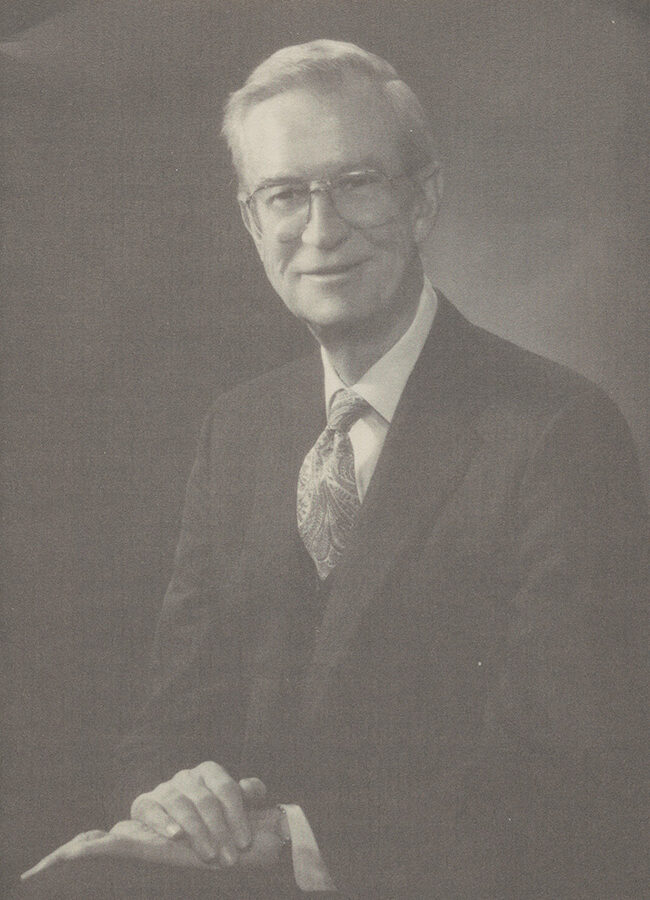

Herbert Buell West (1916-1990)

He was an inveterate tinkerer, a man whose eyes lit up when he was faced with a knotty problem, whether the difficulty was an awkward sentence, an organizational impasse, or the vast cares of his beloved New York City. This zest for problem-solving, coupled with an unshakable moral integrity, made Herbert Buell West an ideal leader for New York’s philanthropic foundation, The New York Community Trust, of which he was president for 22 years. Herbert was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on April 19, 1916, the youngest of five children. He knew only a few years of family prosperity before the recessions of the early 1920s undercut their security. When Herbert was 9, his father died of a heart attack, and the West family fell on hard times.

Herbert’s mother was a strong influence on his character. She was a small, proud, and intelligent woman, forced to go to work to make ends meet but unbowed and devoted to her children. She cultivated Herbert’s thirst for learning. When the little boy was not selling magazine subscriptions to bolster the family income, he was poring over volumes of “The Book of Knowledge,” and she taught him that a quick brain, hard work, and high morals were the keys to success.

Ideas, energy, and integrity characterized Herbert West’s life.

The Power of Words

One of Herb’s earliest paying jobs was at a Birmingham print shop after school. Handling the inky metal type, watching the huge sheets of paper roll off the press, Herb fell in love with words, the way they looked on a page and their emotional power. Whatever else he became—and he was many things—he was first a writer. All his life he would rarely be without paper and pen, pinning down his flying thoughts on endless yellow pads, business cards, and envelopes.

He worked his way through school as a writer, entering Birmingham-Southern College when he was 16, armed with an offer from the Birmingham News to pay 10 cents an inch for a sports column. Herbert, who knew little about sports, promised to deliver the column—and then, with typical industry, set out to learn everything he could. His luck held, and the Birmingham-Southern football team won often that first year—providing plenty of scoop opportunities for an eager writer with looming tuition payments.

He worked his way through school as a writer, entering Birmingham-Southern College when he was 16, armed with an offer from the Birmingham News to pay 10 cents an inch for a sports column. Herbert, who knew little about sports, promised to deliver the column—and then, with typical industry, set out to learn everything he could. His luck held, and the Birmingham-Southern football team won often that first year—providing plenty of scoop opportunities for an eager writer with looming tuition payments.

In 1934, during his college summer vacation, Herb took a bus from Birmingham to New York City to visit his older sister. He had only enough money for a slim-budgeted two weeks, but when he wangled a job at the New York Public Library reshelving books at $50 a month, he was free to explore the city for the entire summer. The tall, slender, soft-spoken Southern boy drank in New York’s noise and vitality and was thrilled.

Two years later, Herb was back, a college graduate with a year of promotional work for the Wrigley Co. under his belt. He was only 20, but he was sure of two things: He wanted to live in New York, and he wanted to work as a writer in advertising.

After making the rounds of a number of agencies, he heard of an opening for an assistant to John Caples of Batten, Barton, Durstine, and Osborne. Herb had read and admired John Caples’ best-selling book on copywriting, and he applied for the job. As a trial, Caples asked him to conceive and write two sample advertisements for an agency client. The next day, Herb returned with 16! He was immediately hired by BBDO.

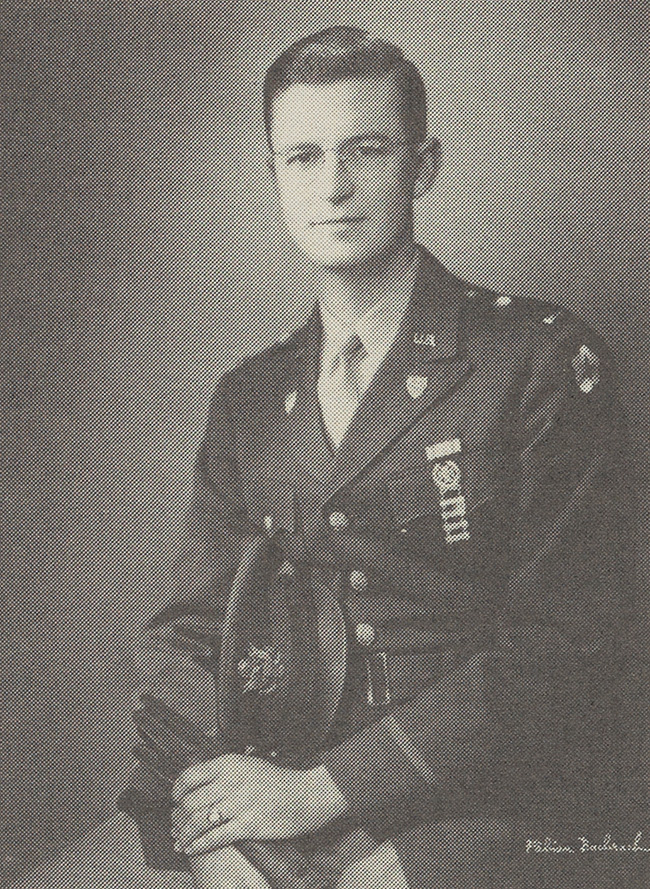

Five years later, World War II interrupted Herb’s copywriting career. From 1941 to 1946, he served with the U.S. Army Adjutant General’s Corps in the Office of Dependency Benefits, where he attained the rank of major and was decorated with the Legion of Merit. Much of his time was spent speaking to groups around the country, explaining the available benefits and interpreting regulations. The work gave him considerable administrative experience, which he carried back to civilian life.

Five years later, World War II interrupted Herb’s copywriting career. From 1941 to 1946, he served with the U.S. Army Adjutant General’s Corps in the Office of Dependency Benefits, where he attained the rank of major and was decorated with the Legion of Merit. Much of his time was spent speaking to groups around the country, explaining the available benefits and interpreting regulations. The work gave him considerable administrative experience, which he carried back to civilian life.

He was 30 years old when the war ended. His Army work had exposed him to some of the challenges and excitement of leadership, and on his return to BBDO, he chose to move from copywriting to account management, beginning as an account executive and rising to account supervisor and vice president.

Within a year of his military discharge, Herb also made a major change in his personal life. A friend told him, “I’ve met a whole covey of Southern women on East 46th Street. Want to meet one?” He met Maria Selden McDonald of Faunsdale, Alabama, on a blind date in March, and they were married November 29, 1946.

Family Man

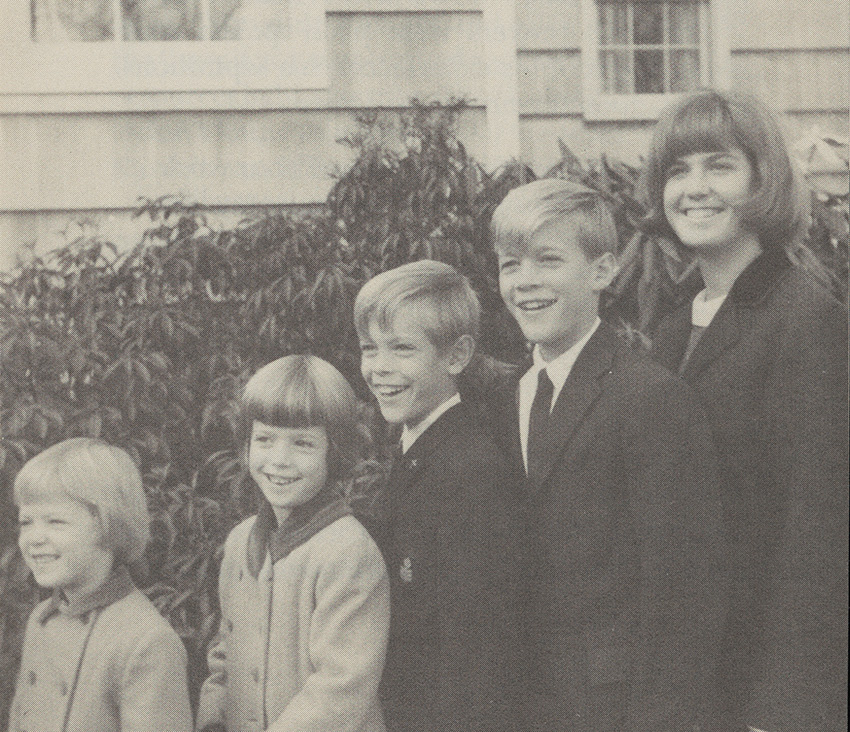

Herb and Maria lived in Manhattan until 1951, when they moved to Connecticut. They built their home in Darien in 1954, and their house and its 2 1/2 wooded acres would be the hub of their activities. It was in this rambling white Colonial that they brought up their five children, born between 1949 and 1961: three daughters, Newill, Selden, and Jane; and two sons, Herbert Jr., and McDonald. “For 24 years,” he wrote in 1973, “I have been celebrating birthdays, drying tears, telling bedtime stories, applauding school plays, and observing first-hand how the world changes. In short, I have a family.”

The house on Driftway Lane provided endless opportunities for work and satisfaction. For years, weekend plans began at the Saturday morning breakfast table, where Herb made long project lists on yellow paper. Most sunny days found the senior Wests outdoors, working together companionably with hammers, drill, or garden spades. “This was our golf game, our sailing,” said Maria.

Herb passed on to his children the conviction that with ingenuity and elbow grease they could conquer most household problems. Finding solutions was the great pleasure, whether the puzzle was large or small. “My father loved systems and order,” Selden said, “and he loved puttering to get there.” When Herb went on shopping expeditions, he was apt to return home bearing one or two new gadgets. “I just thought I’d give these a try,” he’d say with scarcely concealed enthusiasm.

The Inner Man

Religion was always an important part of Herb’s life. Both a brother and a nephew were Episcopal bishops; he was a prominent layman in the church, and from 1961 to 1968 he served as a member of the national executive council of the Episcopal Church. In 1974, Seabury Press published a book of Herb’s prayers and meditations, “Stay With Me Lord: A Man’s Prayers.”

Herb’s prayers were plain-spoken communications of his experiences, aspirations, disappointments, and joys. A sample:

“Lord, I know that the tools of your work are simple human lives. Please use my life. Help me to keep it in harmony with your purpose, so that the strength, energy, and talent you have given me are useful to you, day by day, in the commonplace affairs of life. Amen”

Television and Nonprofits

In 1948, BBDO asked Herb to create and head its first television department, an assignment that perfectly suited his love of discovery, challenge, and problem-solving. As his eldest daughter, Newill, said, “Daddy had such an incredible thirst for knowledge and a delight in it. The world was a cornucopia of things to know about, and think about, and experience and to have in your head as components to bring into play, either for pleasure or to achieve a goal.”

After the television department was launched, Herb returned to account work. He found he enjoyed working on BBDO’s not-for-profit accounts, which he would do frequently for such groups as Columbia Presbyterian Hospital and New York Hospital. “Volunteering and public service were part of his being,” his wife Maria said.

At BBDO, meanwhile, he was becoming increasingly aware that few people stayed in advertising until retirement at 65. Herb was 49 when he and Maria rented a cottage in Florida and walked the beaches discussing life options. Teaching was a possibility, public television was alluring, but “I’d always been intrigued by the idea of foundations,” Herb said many years later. “You didn’t go out and rattle a tin cup all the time; if you wanted to do something, you had resources behind you to do it. I thought to myself, ‘I don’t know anything about foundations, but I think it would be very exciting.’ ”

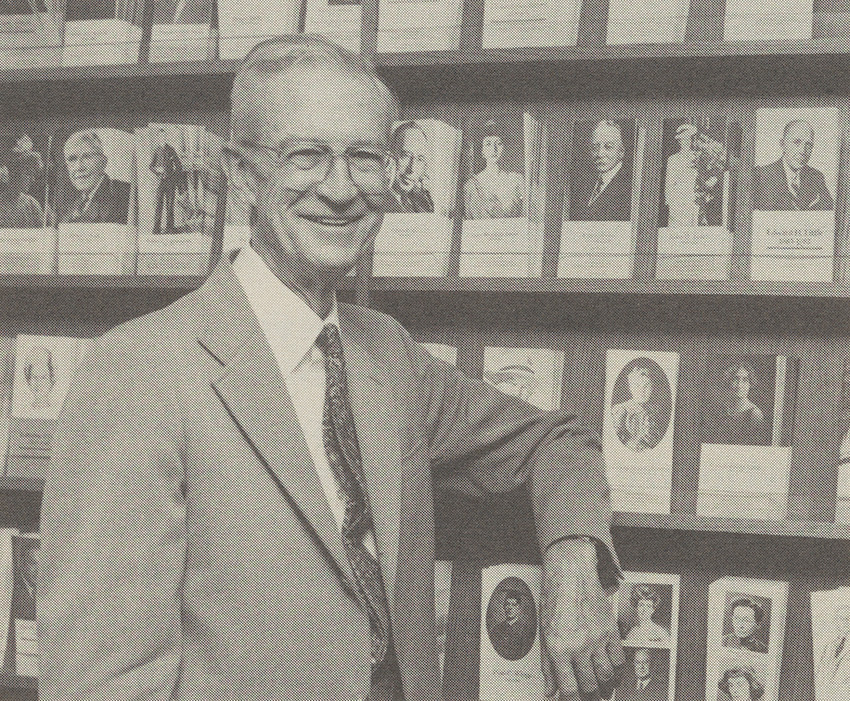

An acquaintance from his volunteer work recommended Herb to Ralph Hayes, who was about to retire after 44 years as president of The New York Community Trust. In 1967, Hayes announced that Herbert West would succeed him as leader of what was then the fourth-largest community foundation in the country. Under Herb’s leadership, The Trust would grow tremendously. Over the next 22 years, the assets of The New York Community Trust rose from $61 million to $829 million.

Leader and Innovator

“My father was really sort of born again at The Trust,” said Newill. “It was ideal. Working there satisfied both his wish to do good and his entrepreneurial drive to build something.” Seconded his son Mac: “He felt there was much more he could share with people in philanthropy than in advertising. I think it fulfilled his spiritual growth.”

Herb was the community foundation’s marketer, taking everything he had learned about salesmanship in advertising and converting it to the needs of the foundation world. His approach—emphasizing service to donors and potential donors—was revolutionary.

“Raising money is based on the principle of free speech,” Herb said. “Anybody can try to raise money for anything, as long as it’s legal. You cannot protect your turf. You can only protect yourself by offering more than anybody else: more expert knowledge of your community, and more service, convenience, and credibility with donors.”

Under Herb’s leadership, The Trust expanded both its grants program and its financial staff and improved the ways it attracted and disbursed money. An important innovation was Herb’s decision to appeal to the advisors of wealthy people—the lawyers, accountants, and estate planners—and to invite both donors and advisors to monthly breakfasts, each of which was focused on a current city problem, such as AIDS, the environment, or education.

“Frederick Goff started the community foundation movement, but Herb West helped give it momentum at a critical moment,” said James A. Joseph, president of the Council on Foundations. “He understood better than most that philanthropy is not a given. It needs a catalyst, a vehicle to bring community needs and community assets together. Ideas were always fermenting.”

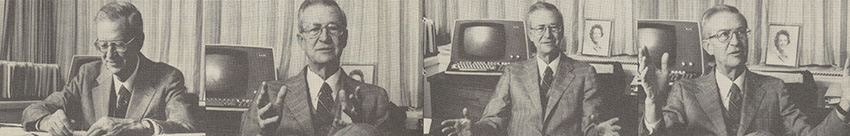

“He had the most youthful, creative, energetic mind of anyone I’ve ever worked with,” said Lorie Slutsky, who later became his successor. “And the quickest. He came in every day thinking about what he could do next. He would get off the train—he had an hour’s ride—and come in with 3-by-5 index cards in his pocket, pull them out and say, ‘Let me tell you about this . . .’ and start in on a new idea he came up with on the way in.”

William Parsons, who worked with Herb for 22 years—18 as chairman of The Trust—said: “Herbert West had great depth. His deep commitment to the betterment of mankind can be seen in his extraordinarily able work at The Trust, where he attracted enormous amounts of charitable funds, arranged for their expert management, and disbursed them for worthy causes with great wisdom and understanding. His deep religious feelings penetrated his personal and professional life and brought to them both a spiritual sense of purpose. His ease in working with all kinds of people and all kinds of ideas permitted the fulfillment of his deepest aspirations. Our friendship will always be one of the great treasures of my life.”

Eager to help

By 1986, The New York Community Trust had become the largest community foundation in the country. Typically, Herbert West looked for ways The Trust could, in its turn, boost smaller institutions. He spent hours meeting with people from small community foundations. “He sat with those foundations and listened to their problems as if they were his own,” Lorie Slutsky said.

He was generous not only with his time but with his ideas. “Everyone in the foundation community uses at least one of Herb West’s ideas,” wrote Bruce L. Newman, executive director of The Chicago Community Trust, ticking off Herb’s many contributions. “The list goes on and on.” Herb’s 22 Ways to Use The New York Community Trust, written at home in longhand on a yellow pad, was adapted by more than 100 foundations, to his great pleasure. “He was able to get things out on the street,” remembered one colleague. “Unselfish is the number one word,” another said.

Herbert West was a thoughtful presence on many boards: the New York University Medical Center, the Council on Foundations, the National Charities Information Bureau, the Foundation Center, Welfare Research Inc., Travelers Aid International Social Service, and North Country School. He was president of Community Funds Inc. and The James Foundation. In his hometown of Darien, Connecticut, Herb served as president of A Better Chance, head of the Community Council, and senior warden of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

Peaks and Valleys

At 73, believing it was time for new, young blood to take over at The Trust, Herb planned his retirement for December 1989. In the West Christmas letter, Herb wrote: “It has been a year of very high peaks and one valley.”

The high points were the many testaments and honors he received that year from all over the country, capped by the retirement dinner given by The Trust at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Nov. 16. More than 300 friends, relatives, and colleagues gathered to celebrate his 22 years of service. Susan Berresford, vice president of the Ford Foundation, saluted Herb as “a shrewd public servant, a wise philanthropist, a builder of enduring institutions, and a kind and generous man.”

“I’ve been helping to build something very meaningful to me—a facility for people who want to help make the world a little better,” Herb said that night. He looked thinner than usual, worn, even frail, but his eyes still burned with enthusiasm. “There’s a tremendous amount of generosity in America—the pioneer spirit of helping one’s neighbor in times of trouble is very much alive and may be stronger than ever. In fact, the world has gotten so complicated that I think there’s more generosity around than there are facilities for handling it with satisfaction. That’s why it has been so much fun to work on building The New York Community Trust.”

The one valley Herbert alluded to was the discovery, a month before his retirement, of his incurable cancer. He had enjoyed planning his “third career,” a busy combination of consulting work for The Trust and the pursuit of myriad personal interests—gardening, cooking, computer desktop publishing, genealogical research, travel with Maria, visits with children and grandchildren. Though he looked forward with courage, there was no more time. On January 14, just 10 weeks after his illness was diagnosed, Herbert West died at home in his sleep.

Grants from The Herbert B. West Fund, instituted by friends, colleagues, and organizations from all over the country, have supported immigrants, training for unemployed youths, mental health care for people with disabilities, an accurate and fair census, education, the environment and many more causes to “help make the world a little better.”