Greek immigrant invented Blue Coral, a sparkling metal polish for luxury cars.

Harry D. Triantafillu (1895-1976)

Sea creatures and sweat shared the cellar laboratory as Harry D. Triantafillu spent the “Roaring Twenties” bent over the mixture he would later patent as the Blue Coral Treatment, a preparation that, beginning in 1928, put a long-lasting sheen on Cadillacs and other cars.

Harry himself was an equally rare combination: a poor Greek immigrant who blended the persuasiveness of a salesman, the clarity of the Bermuda skies, and the work ethic of White Plains, New York, into a polished portrait of success.

Harry first breathed salt air on February 10, 1895, in the small town of Velestino on Pagasitikos Bay, 200 miles north of Athens, Greece. As a boy, Harry read widely and studied theology, preparing to follow his father into the Greek Orthodox priesthood. But stories of America fired his imagination, and Velestino began to feel too small for Harry’s ambitions.

A New World

His father must have understood that the priesthood would not suit Harry, for he packed his son off at age 14 with the $20 gold piece Harry would need to pass inspection at Ellis Island. Three weeks later, Harry’s ship docked, and the teenager rolled up his sleeves and began his quest as a dishwasher.

The Aegean climate had not prepared young Harry for the vicissitudes of New York weather, however, nor had his studies toughened him for long hours of menial work. Harry fell ill, and a doctor advised him to either return home or move to an area more like his native land.

Harry, never one to look back, chose Bermuda. Despite his weakened condition, Harry earned his passage by shoveling coal for 48 straight hours until the white sands of Bermuda sparkled on the horizon.

Figuring a fellow countryman would be his best bet for decent employment, Harry used charm and his limited command of English to search out the island’s only other Greek inhabitant.

His instincts were right—as they would be many times again. The older gentleman was the captain of one of the popular glass-bottomed boats that let tourists see the brilliant fish and coral formations in Bermuda’s waters. He put Harry to work cleaning the boat.

Every day, Harry washed windows and polished brass until the boat sparkled and his shoulders ached. But his adolescent mind nurtured the thought that there must be an easier way to make things shine and protect their surfaces longer.

He even knew what he would name it: Blue Coral, after the azure skies and fantastic coral formations of Bermuda. Years later, the name that distilled the beauty of this Atlantic island would become an unforgettable label for the product Harry imagined, a compound that ultimately would draw on the sea for its magic ingredient.

To turn his idea into reality, Harry knew he needed to return to New York. He spent long nights studying English with two teachers who lived in his boardinghouse. After 18 months of study, Harry returned to New York with a new command of the language and a single-minded determination to invent the world’s best metal polish.

World War I intervened. To protect his new country, Harry took to the trenches of France and Belgium with New York’s crack 7th Infantry Regiment. When he retired his uniform after Armistice Day, it bore the Ypres-Legun Medal for distinguished service and a Purple Heart, earned for surviving a mustard gas attack.

A civilian again, Harry needed a job while he pursued his polish formula. To gain a sense of the business environment, he examined what people were buying in post-war New York. Turkish cigarettes had become the rage in the new liberalism of the day; even women were smoking in public for the first time. Harry reasoned that, since Greeks were heavy smokers, he was likely to do well selling cigarettes.

Once again, Harry’s instincts were right on the money. He joined Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, where his persistence and charm propelled him quickly to top salesman and a position as group manager. Liggett & Myers was expanding into new overseas markets and invited Harry to represent them in China.

But Harry’s future in tobacco was deflected by a normal event for a man in his 20s: love, in the person of Gertrude Van Vaulkenburgh, a fellow tenant in Harry’s rooming house. When Harry asked Gertrude to pass him the rolls at dinner, she threw one instead. This high-spiritedness impressed Harry. And Gertrude—whose Dutch ancestors settled New Amsterdam in the 1600s—wasted no time telling Harry what a bad idea she thought China would be.

Harry chose Gertrude over China. He resigned from Liggett & Myers and married Gertrude a month later without, as he wrote, “even having a job!” But he now had invaluable business and sales experience to offer a new employer—and use to build his own company.

Harry went to work for a New England candy company, again breaking previous sales records. But the dream of perfecting a better polish than paste wax, longer lasting and easier to apply, occupied his waking thoughts. He worked nights and weekends on the formula in a basement on lower Main Street in White Plains. By 1928, Harry at last had a product that met his expectations.

The New Product

From the beginning, it was company policy to refer to the product as the “Blue Coral Treatment,” rather than just another cleaner and polish. In fact, while the term helped distinguish Blue Coral from its competition, “treatment” also described the two-part process Harry had invented, in which a liquid cleaner was followed by a protective sealer.

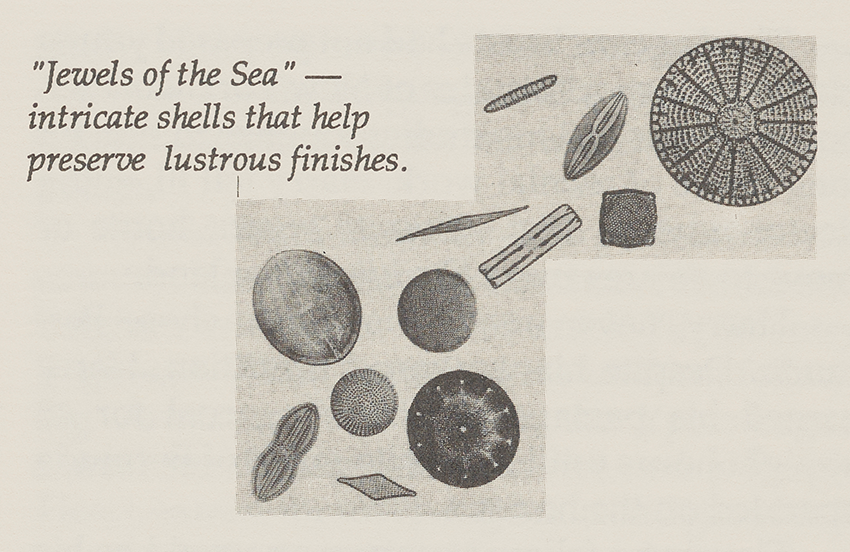

Suspended in the cleaner were minute particles of fossilized aquatic plants and animals, which imparted a delicate burnishing action without damaging painted surfaces. Highly porous, the siliceous particles absorbed grease and dirt far better than traditional cleaners. The all-weather sealer, applied later and buffed, employed a carnauba palm wax commonly used in candle making to produce a superior, scratch-resistant, durable finish that beautified and protected a car for up to one year.

Harry had a good product, memorable name, sales savvy—and only $340. He packaged the first 14 bottles of Blue Coral himself, using bottles borrowed from a local druggist. With the sealer, which came in a can, Harry’s product line was ready to market—just before the stock market crashed.

Happily for Harry, the Depression presented more help than harm to the fledgling business. He had decided to target the dealers of America’s premier luxury car—the Cadillac—as his primary market. With luxury car sales plummeting, the dealers were interested in ways to make their cars stand out from the competition.

Harry never forgot his first sale. After nine months of calls on the manager at New York City’s large Cadillac dealership—and many free samples—he still had not received an order. Suddenly, the manager called to invite Harry to demonstrate the Blue Coral Treatment before the entire New York Cadillac service organization of 60 men.

Harry applied his sales ingenuity as well as Blue Coral Treatment to that product demonstration. Before his somewhat skeptical audience, Harry burnished and polished a brand-new Cadillac—on only one side. The difference between the two sides was startlingly apparent. The treated side gleamed and sparkled, reflecting clouds in the sky.

Harry seized the moment to describe how the new finish was also streak proof, rain proof and spot proof, and pledged that it would be sold only through car dealers in the top-quality bracket. The meeting lasted well into the night. The next day, the manager called with an order for 1,000 bottles of Blue Coral, sending Harry and Gertrude into a frenzy of activity that wouldn’t let up for a lifetime.

Sometime later, Harry paid a cold call on Cadillac’s national chief for parts and service. Walking into the Detroit headquarters, he was surprised to find that an entire advertising campaign featuring his product was already in the works. The company wanted to order Blue Coral for all its dealerships nationwide.

The Cadillac executive chided Harry, asking, “Where have you been? Why sell the long, hard way through dealers when we were looking for you?” Harry responded politely, but he always felt the real lesson lay in that first sale. “The truth,” he would say to his own employees later, “is that the boss buys when you get the staff behind the product.”

Blue Coral was launched. Harry rented a factory to fulfill the large order he received from Cadillac in Detroit, and similar orders arrived shortly from Packard, Pontiac, and Lincoln-Mercury. In later years, the company expanded its customer base to include boat manufacturers, the armed services, and selected home markets.

In 1956, Harry’s company—named H.D.T. Company Factors after his initials—moved into a beautiful new plant of its own in White Plains, New York. The 37,500-square-foot, coral brick facility was hailed as a model of enlightened industrial design and attracted considerable attention in the community. Employees commented that it was clean enough to “eat off the floors,” and passersby sometimes took it for a hospital.

Flower beds and shrubs surrounded the model factory. The Greek name Triantafillu means “a rose” (literally, “30 petals”) and Harry’s interest in beautification extended to the community at large, where he contributed regularly to local projects. Many years later, after Harry’s death, the White Plains Beautification Society used funds he contributed to build a sculptured fountain on a prominent downtown mall. They named it after Harry.

Success didn’t change Harry much. He and Gertrude spent their entire married lives in the same modest home in White Plains. Their prime luxury was apt: a new Cadillac every year. Harry worked seven days a week, proud of Blue Coral but unwilling to rest on his laurels. Vacations were rare. Even when his mother was ill, Harry usually flew to Velestino and came back the next day. He read voraciously, mostly self-help books, underscoring passages to be remembered. He dressed with care, each Sunday donning a fresh suit for the coming week, chosen from among 35 custom-tailored cashmere and silk suits in his office closet.

Harry’s employees recall that, when he came through the plant, he protected his clothes with a large apron and cushioned his feet in embroidered black velvet slippers from Greece. They found his management style fair but demanding. “Use your head for more than a hat,” he would tell them. And he insisted that every order had to be shipped out the same day it was received.

“A Brighter Future Than IBM”

But his seriousness was tempered by the moments of humor and charm that had distinguished his early success in sales. Blue Coral’s balance sheets occasionally tempted corporate suitors looking at acquisition, and although Harry never seriously considered selling, he enjoyed the discussions. One gentleman from a much larger and better-known national company asked Harry how much he wanted for Blue Coral.

“Well,” said Harry with a straight face, “IBM is selling for 30 times earnings. Since Blue Coral has a brighter future than IBM, Blue Coral must be worth more than 30 times earnings!”

“Harry, you really don’t want to sell your company,” said the prospective buyer as he left.

With no children of their own, Harry and Gertrude reached out to other young people. Every Christmas, they invited Greek exchange students from the New York area to join them for an American Christmas dinner and Greek songs. But first, Harry, the self-educated, lifelong learner, would don his embroidered slippers and lead the students on a tour of his factory, enthusiastically describing Blue Coral’s manufacturing, bottling, and shipping methods.

Through the Anglo-American Hellenic Bureau of Education that Harry founded and supported, the Triantafillus also provided scholarships to hundreds of Greek students attending college in the United States. Harry was proud that many of these students went on to hold important posts in the Greek government. Others joined university faculties, became architects, or took engineering positions with international companies.

The Triantafillus corresponded regularly with many of the young people who benefited from their generosity. They were particularly touched when, at one of the Christmas gatherings, visiting Greek students presented Harry and Gertrude with a copy of Rembrandt’s “Aristotle with a Bust of Homer” in honor of their long financial support and friendship.

Inventor, entrepreneur, star salesman, Harry Triantafillu worked until three weeks before his death in 1976 at age 81. Gertrude, who taught kindergarten in White Plains, lived 10 more years. And Blue Coral, which Harry refused to sell during his lifetime, was sold two years after his death and was moved to Cleveland, where it continues today.

Blue Coral was not Harry’s only legacy. Through a fund in The New York Community Trust and The New York Community Trust – Westchester, Harry remembered his home in Greece, his home in America and his love for learning and students.