She founded Loehmann’s and launched the discount fashion industry. Her Fund at The Trust supports public education and more.

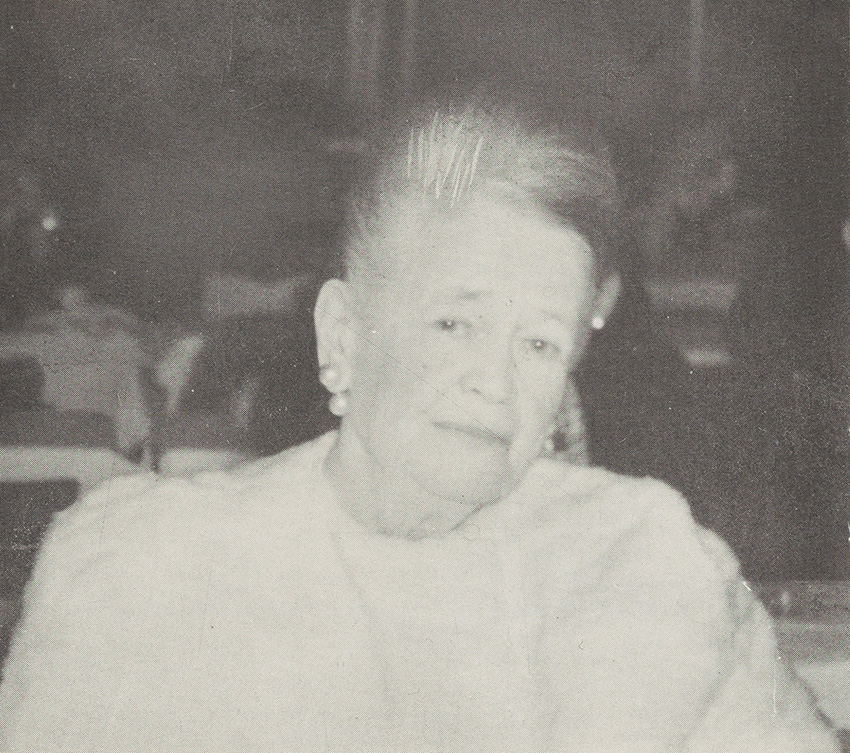

Frieda Mueller (1873-1962)

Before the terminology emerged in the late 19th century, there were New Women—women who crossed the prairie in covered wagons, homesteaded, pioneered and sometimes, as in the case of Frieda Mueller, built an empire. Frieda was driven not by personal ambition but by the need to provide for her family. Had life not dealt her a stunning blow, she probably would have been content with the role of wife and mother. Instead, she created an industry.

Frieda Mueller was born in October 1873. While she was still a child, her family moved from Hoboken, New Jersey, to Cincinnati, Ohio. When she was about 19, she met Charles Loehmann, a flutist who played with John Philip Sousa’s band. They married in the early 1890s, established their household in the city’s Clifton neighborhood, and raised their three children—Charles, Marjorie, and William—each born within two years of one another.

Life seemed settled and serene until paralysis of the lip brought Charles Loehmann’s career as a flutist to an end. He opened a haberdashery in the outskirts of Cincinnati, and Frieda joined him in the business. Frieda brought resourcefulness, courage, determination, and a genius for organization to her new career. She was an innovator whose concepts of merchandising formed the basis for the discount fashion industry.

Frieda’s success, summarized later in glowing tributes, makes it seem that her path was straight up. In reality, there were setbacks and disappointments. At first, the haberdashery did well. Frieda introduced a line of women’s skirts and blouses at discount prices. The sales curve rose. Encouraged, Frieda and Charles expanded and relocated in downtown Cincinnati.

This proved to be disastrous because established retail stores complained to the manufacturers, who, in turn, refused to sell to Loehmann’s at discount prices. Ultimately, Loehmann’s went bankrupt, and Frieda traveled to New York City to look for work. In 1916, she accepted a job as a buyer for a New York City department store, and the family moved from Cincinnati to Brooklyn.

Frieda was called upon to capitalize upon misfortune when one day, the merchandise she had ordered for a storewide sale failed to show up. In desperation, Frieda rushed to Seventh Avenue and bought hundreds of samples. The public snapped them up. And Frieda began thinking: Why not start her own business selling designer samples and end-of-season surplus apparel at discount prices?

Frieda took the plunge. In 1920, the first Loehmann’s store opened and operated out of Charles and Frieda’s home in Brooklyn. Every morning, Frieda headed to Manhattan to purchase apparel. The children stayed at the store to sell the merchandise “Mama” had purchased the day before.

The popularity of Loehmann’s grew rapidly: Customers did not mind crowding into a small space to buy fine designer clothes at low prices. The discount fashion business was born.

Frieda soon found it necessary to expand her operation and moved to a basement store on Nostrand Avenue furnished with only clothing racks and a table. By 1930, another expansion was called for, and a larger store was opened at 1476 Bedford Ave.

Frieda and her husband lived in an apartment above the store, guarded by two watchdogs. The business continued to grow and eventually became a $3 million-a-year enterprise. Frieda’s original customers from Brooklyn continued to shop at the new store, along with bargain hunters from as far away as Staten Island and the Bronx, who came by subway, and luminaries of New York society and Broadway stage, who arrived in chauffeured limousines.

The store’s physical plant began to reflect its fiscal success as well as “Mama’s” taste. She furnished it with unusual antiques and gilt furnishings, which made customers feel they had entered a very special environment.

A New York Herald Tribune columnist wrote: “Hundreds of racks of clothes failed to dim the theatrical splendor of Loehmann’s, inside.”

Describing the interior, The New York Times wrote: “Ranks of chandeliers, dripping prisms, enormous paintings, Venetian columns festooned in gold, huge lanterns and torchieres….”

As accessible as the famous store was to the public, the woman behind it remained an enigma. Reporters, eager to tell the story of Frieda Loehmann, could not persuade her to grant an interview. She was, depending on whose opinion you sought, either too shy or simply disinterested. Perhaps it was a combination of the two.

On her annual buying trips abroad and during evenings out in New York, she dressed elegantly. One acquaintance described her appearance at a New Year’s Eve party as stunning, in a white cape and dress with her hair coiffed into a high pompadour. Another recalled the time two fashion editors visited the store on Bedford Avenue and were greeted by Frieda, poised at the top of her marble staircase in a long velvet dinner skirt. This sense of elegance and regalness was a dramatic contrast to her everyday work outfit, a long black, button-down dress, black cotton stockings and black oxfords.

Frieda’s style of buying was as no-nonsense as her work outfit. Early on, she paid only in cash that she carried in thick rolls inside her stocking. Eventually, she carried a checkbook, but “bill me” was not part of her working vocabulary. Frieda shunned the showrooms, preferring to work behind the scenes in the stockrooms, among the shipping clerks and stock boys. They all appreciated her courtesy and integrity, and she showed her gratitude with armfuls of gifts at Christmastime.

For more than 40 years, the men and women of the fashion district—from shipping clerks to manufacturers—admired “Mama” Loehmann for her uncanny ability to predict style trends, her shrewdness as a businesswoman and her generosity.

Designers like Norman Norell and Adele Simpson appreciated and admired Frieda for her ability to buy and sell creations that languished on the racks of fancy Manhattan stores at the end of a season. Manufacturers, too, benefited. As one explained: “ ‘Mama’ provided an outlet for our mistakes.”

One indisputable fact about the elusive Frieda Mueller Loehmann was that she enjoyed her work. Two designers once traveled to Brooklyn on a Sunday to look at the famous Loehmann’s store. When they peered inside, they saw a woman on her hands and knees cleaning the plate windows. It was Frieda. “I’m having a wonderful day,” she said, greeting them warmly, inviting them inside. “My children have gone to the country, and I can do just what I want.”

Charles Loehmann died in the 1940s, and shortly afterward, Frieda began to turn more of the store operations over to her children. However, she continued to be the buyer and guiding spirit behind the scenes. Her son Charles decided to establish his own company, also called Loehmann’s, which became a chain with about 100 stores in 17 states at its peak in 1999, but Frieda elected to operate the Brooklyn store and did not join him.

Frieda died at Long Island College Hospital on September 22, 1962, one month before her 89th birthday. She had made her daily rounds in a wheelchair until two weeks before her death.

Since the neighborhood had become increasingly less fashionable, the family decided to sell the Bedford Avenue store after Frieda’s death. The furnishings were sold at an auction attended by antiques dealers as well as loyal customers who came to find one last bargain at the original Loehmann’s.

Pausing to pay her tribute, one long-term business associate said, “She was a great lady. She could see more with her eyes half closed than others with their eyes wide open.” Another said, quite simply: “She was loyal—always a friend.”

After three bankruptcies and numerous new owners, the last Loehmann’s stores closed in February 2014, including four in New York City. “I really feel it is the end of an era,” said Mary Hall, who blogs about bargains at The Recessionista. “For many years, it was one of the few stores women could go to for upscale designer goods that were reasonably priced but of good quality.”

To memorialize Frieda Mueller’s generosity and kindness, as well as her pioneering spirit, The Frieda Mueller Fund was established by her granddaughter at The New York Community Trust for public educational and charitable purposes.