Anchoring a Brooklyn Family

Eugene “Gene” Di Mattina (1926 – 2010)

One of the proudest moments of Eugene Di Mattina’s life came on July 4, 1976, when televisions across the country transmitted images of the celebration of America’s Bicentennial. Sixteen tall ships from around the world crisscrossed New York Harbor amid 20,000 other watercraft ranging from weekend sloops to the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Forrestal, carrying President Gerald Ford. More than five million people watched from shore and tens of millions saw the festivities on TV.

It was a powerful moment for Di Mattina for two reasons. First of all, it was proof of the importance of his business of supplying massive anchors and other heavy equipment to many of the vessels in the harbor. Second, the Bicentennial was a reminder of how far his family had come since March 6, 1908, when his father, Dominick, then 19, stepped off the steamship Sicilia at Ellis Island. He had $10.

Dominick had crossed the Atlantic with 1,400 others, most in third class like him, to escape poverty and political instability in southern Italy.

Stromboli Origins

Dominick came from Stromboli (which, by the way, has little to do with the calzone-like mozzarella and pepperoni turnover first concocted in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). The most isolated of the Aeolian Islands northeast of Sicily, Stromboli is home to one of the world’s most active volcanoes. To this day, nearly everything needed there comes by boat. Now day-tripping tourists in the Mediterranean marvel at the island’s black sand beaches and continuously smoking volcano, but for most of the 20th century, Stromboli was a place people wanted to leave.

When the Di Mattina family speaks of Stromboli, conversations tend to circle back to the 1950 neorealist film Stromboli, Land of God directed by Roberto Rossellini and known for its unsparing portrayal of life after waves of emigration had reduced the population from several thousand to several hundred.

Used Rope

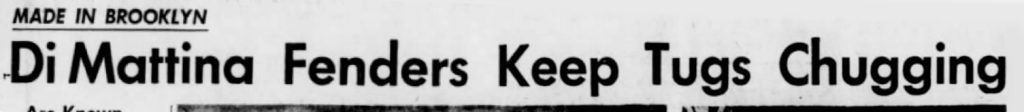

Dominick Di Mattina’s father, like his father and grandfather, relied on the sea to make a living. The family owned boats for shipping “wines, beans, and flour,” according to one account. They also made bow fenders, “picturesque masses of rope” once widely used to protect the bow, stern and sides of boats from “harsh encounters and shattering impacts against piers, docks, and other vessels.” Today, fenders are more likely to be made of rubber or plastic.

Dominick gravitated to Red Hook in Brooklyn, then one of America’s busiest freight ports and home to many of the two million Italians who came to America between 1900 and 1910.

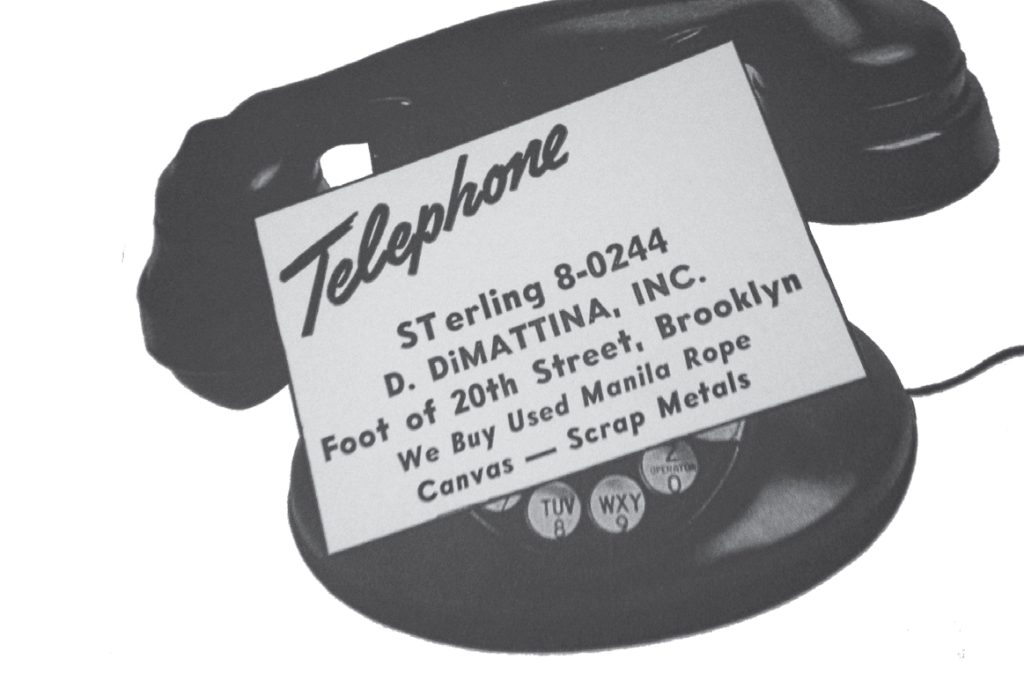

“My father started out making fenders with used sisal and hemp rope” at the foot of 20th Street on the harbor, recalls Eugene Di Mattina’s younger sister Roseanne Barker.

Dominick Di Mattina later rented a pier on the Gowanus Canal, where “tugs, barges, and other craft” could dock for “fittings,” according to a story in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Men standing at benches wove “patterns as intricate and carefully worked out as the pineapples and pinwheels on a luncheon doily,” according to the story. The fenders weighed up to four tons each and became bleached white by the sun and salt water.

Tragedies

Dominick’s younger brother, Antonio, joined him in New York after serving in the Italian navy during World War I. Dominick married Antoinetta Parascandola, and their first son, Vincent, was born in 1921. A daughter, Josephine, came the next year. They lived in a brownstone they owned at 350 Clinton Street, in the neighborhood now known as Cobble Hill.

In 1923, Antoinetta died of pneumonia at age 26. Dominick married Antoinette’s younger sister Julia the following year.

Dominick moved his young family from Red Hook to a new home in Baldwin, Long Island. The house was built by the same family that had sponsored him in 1908. Dominick had sought them out for the job, an example of the kind of loyalty he became known for. The tiles on the bathroom floor spelled out his initials, D.D.M.

On Thanksgiving Day, 1926, Blaise Eugene Di Mattina was born in that house. He eventually became known as “Gene” among family and friends, and “Mr. D.” among those who worked for him.

The family soldiered through the Great Depression. They moved back to the Clinton Street brownstone on orders of doctors who believed the Baldwin climate was unhealthy for Di Mattina’s half-sister, Josephine, according to Barker. Josephine had rheumatic heart disease, a life-threatening illness at the time.

Di Mattina’s sister Annette was born in 1934, followed by Roseanne the next year. Josephine died in March of 1937 at age 14.

Growing Up in Brooklyn

During the 1930s, the growing Di Mattina family business included a waterfront taxi service operated by an uncle. The Josephine ferried sailors, engineers, and visitors among the barges, tankers, schooners, and freighters anchored in Red Hook and nearby Bay Ridge Flats, charging a dollar per passenger. The family used another boat, Maria, for chartered fishing trips.

Di Mattina went to high school at St. Francis Prep, three blocks from home. He joined a football program whose alumni included Vince Lombardi, who went on to become the legendary coach of the Green Bay Packers.

During Gene’s freshman year, his father bought at auction the 18,450-pound anchor of a U.S. Navy cruiser used in the Spanish-American War and sold it to a customer in Pennsylvania, according to the local press—the kind of transaction that would later become a big part of the Di Mattina family business.

A year later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II. The Di Mattina family moved from Clinton Street to a larger house in Bay Ridge the following year because Di Mattina’s mother was expecting her fourth child. Josephine, named after his late half-sister, was born in 1943.

Di Mattina did well enough at St. Francis to graduate a semester early. The 1944 school yearbook reports he played junior varsity baseball and football, varsity volleyball, and had been a member of the French and Latin clubs. Decades later, his sister Roseanne Barker remembers that he won a medal for four years of excellence in math. He loved music and played the piano well.

World War II

By 1943, World War II had not yet begun to shift to favor the Allies. Di Mattina was determined to sign up for the Navy’s V-5 Aviation Cadet program to become a pilot. But he needed parental approval because he was only 17.

“There was an uproar in our house,” recalls Barker. “He told my parents he would leave home if they didn’t allow him to enlist.” They relented.

Di Mattina trained at Vermont’s Middlebury College and at the Great Lakes Naval Station on Lake Michigan before being sent to San Diego, says Barker. But by early 1944, the Navy didn’t need more pilots. So Di Mattina was assigned as a radioman on a ship headed to Japanese-occupied Guam.

Six weeks after the Normandy invasion, U.S. forces freed Guam from the Japanese. On November 25 of that year, Di Mattina, in his bunk, heard he had a radio message. “He thought that something had happened to our father,” Barker says. But the message was his father wishing him a happy 18th birthday.

Germany and Japan surrendered the next year. Di Mattina received an honorable discharge and returned to work in his father’s marine supply business in Brooklyn.

Though Di Mattina returned unscathed, the war exacted a toll on his family. His older half-brother Vincent received a medical discharge and lived on disability benefits. And by the time the family received news of the passing of Di Mattina’s grandmother in Stromboli, she’d been dead for six months.

The Di Mattinas sent boxes of food to their homeland because of deepening poverty there.

Meanwhile, the U.S. economy boomed. Di Mattina, his father, his uncle Antonio, and his sister Roseanne worked together on the Gowanus pier rented by the Di Mattina Supply Company. The company bought up to 375 tons of manila rope a year and did an increasingly brisk business in the sale of massive anchors, chains, cables, and shackles.

Di Mattina Supply shipped goods to clients in Houston, San Francisco, and beyond. Clients included the U.S. Coast Guard, Army, and Navy.

Storm Clouds

Until the early 1950s, most of the freight ships passing through Red Hook carried break bulk cargo—goods loaded in individual bags, boxes, crates, drums, or barrels by stevedores. Traffic began to decline in the late ’50s with the modernization of nearby Port Newark and the opening of the Elizabeth Marine Terminal, a prototype for ports using standardized cargo containers.

Container shipping meant the end of the break bulk cargo business that had been the lifeblood of Red Hook.

The family patriarch, Dominick, died on March 24, 1955. Di Mattina was 29. His youngest sister, Josephine, had just turned 12. Due to the downturn of shipping in Brooklyn, the Di Mattina family business “wasn’t doing very well,” according to Di Mattina’s lawyer, accountant, and friend Stephen Weiss. The weight of the family business was now entirely upon his young shoulders.

This wasn’t what he had planned; he dreamed of joining a jazz band. “But you can’t do that when you have to take over the family business,” says his niece Julianne Farricker.

A turning point came not long after Dominick’s death, says Barker: Di Mattina heard about an opportunity to supply a load of specialized chain to Republic Aviation, an aircraft manufacturer then based in Farmingdale, Long Island. Di Mattina’s bank declined his $50,000 loan request. His mother drained her savings to lend him the money, and Di Mattina beat out bids by larger competitors.

Di Mattina expanded the business, working with Asian companies, making him a pioneer among American small businessmen. He bought a growing number of his heaviest marine products, such as 15-ton anchors and thick chains, from suppliers in Korea and Japan. He worked with shipyards, offshore drilling firms, mining, heavy construction companies, and quarries across the United States.

After the lower level of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge opened in 1969, Di Mattina moved his operations to Staten Island and renamed the company “Disco International” to reflect its expanded ambitions. Disco was an acronym for Di Mattina Supply Company, though some clients thought it had to do with disco music, which didn’t become popular until the mid-1970s.

Di Mattina branched out further into scrap metal. His business interests came to include heavy equipment for construction as well as investments in wholesale scrap metal yards as far away as Puerto Rico.

Some might say the scrap metal industry’s reputation has suffered because it attracted undesirable people. “The industry has had its share of scoundrels,” says Weiss, but Di Mattina flourished “because he wasn’t one of them.”

Barker says her brother was repulsed by the idea that “some people can never have enough.”

Do the Right Thing

Di Mattina shared many of his father’s traits, including generosity, compassion, and prudence. “Family and friends would come to him for guidance,” recalls Barker, “and he always advised them to do the right thing.”

Di Mattina was known as the life of the party. He enjoyed taking visiting clients to Broadway shows. He was constantly invited to weddings, bat and bar mitzvahs, and holiday events.

He took care of others when things got tough, recalls Farricker, his niece. He was particularly generous in so-called non-deductible charity—gifts and personal loans that were not tax-deductible, says Weiss. The “major charitable endeavor of his life was helping people directly,” Weiss explains.

Anne DeFreese, one of Di Mattina’s long-time employees, and her husband struggled to cover the cost of sending one son to Seton Hall and another to Princeton. Then their daughter, Michelle, a nationally ranked swimmer at Rutgers, decided to pursue her dream of qualifying for the 2004 Olympics.

“Mr. D asked how I was managing,” recalls DeFreese. “I told him that it was a journey,” she says.

Soon after, Di Mattina sent a check to help cover tuition bills. Michelle trained hard but just missed making the U.S. Olympic team.

Simple Living

Despite Di Mattina’s success, he lived very simply, retiring to a modest apartment in Secaucus, New Jersey, in the latter part of his life.

“He could have had whatever car he wanted, but he drove a Toyota Camry and lived in an apartment with rickety old furniture,” says Farricker, his niece. “He had the wherewithal to do as he pleased,” says Weiss, but he was more interested in helping others, especially his niece and nephews, whom he doted upon when they visited each summer.

He delighted in taking them for pasta and broccoli rabe at Nino’s Restaurant on Staten Island and pastrami sandwiches and cheesecake from Harold’s Deli in Edison, New Jersey, recalls Farricker.

Di Mattina talked for years about buying a recreational vehicle and traveling across the country, but he “kept putting off pleasure for himself,” recalls Weiss. Instead, he played a piano in his apartment or watched movies, particularly film noire and Italian films. When Di Mattina wasn’t at work or with his extended family, he liked to hunch over a New York Times crossword puzzle while watching a Yankees game.

One of Di Mattina’s favorite films was Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, released in 1949. Like Stromboli, De Sica’s Bicycle Thief is an important work of Italian neorealism. In it, a thief steals the bicycle a poor man depends on to support his wife and young son. The man scours war-ravaged Rome for his bike, his son in tow, but fails in spectacular fashion. He then yields to temptation and steals another bike to replace his own. He’s caught and publicly shamed for the crime, as his son watches.

For Eugene Di Mattina, the moral of the story was clear: Do the right thing, no matter what.

Not surprisingly, after his death in 2010, Di Mattina continued to help his relatives. He left the rest of his estate to charity through a charitable remainder trust created in his will. The Eugene Di Mattina Fund in The New York Community Trust gives back to the city that allowed his family to thrive. And the fund keeps giving back, year after year.