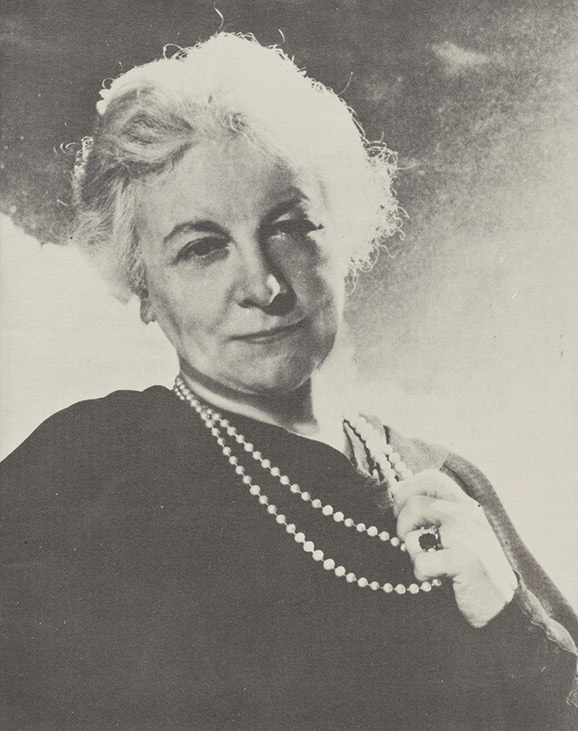

A centenarian who contributed to New York City’s cultural enrichment and served on The Trust’s first distribution committee.

Eleanor Robson Belmont (1878-1979)

“I belong to that group of people who move the piano themselves.” — Eleanor Robson Belmont

She was born in England and transplanted to America. She was an actress of international acclaim. She became the wife, then widow, of a man whose name became synonymous with wealth. She was a dynamic worker for charities and the arts. And she was a writer. Her talents were praised by presidents and playwrights and honored with medals and degrees.

Her life spanned 100 years, and at its three-quarter mark, Eleanor Robson Belmont observed that it seemed . . .

“. . . not one existence with a continuous flow . . . but a life periodically divided into entirely separate compartments. Change of surroundings, interests, pursuits have made it seem more like different incarnations.”

Each incarnation, though, was woven to the next by a common thread: an ability to inspire others, combined with a determination to get things done.

Eleanor Elise Robson was born Dec. 13, 1878, in Lancashire, England, into a theatrical family. Both her grandmother and mother were actresses; her father, who died during her infancy, was an orchestra conductor. The man who became her stepfather while she was still young, Augustus Cook, was an actor, and Eleanor’s mother performed as Madge Carr Cook.

When Eleanor was 6, the Cooks ventured from England to pursue their careers on American stages. It took them only a year to decide to remain in the States, and in 1886, at age 7, Eleanor left England to join them. While her parents toured the country in stock theatre companies, Eleanor studied in a Staten Island convent school. After graduating in 1896, she set off to meet her mother in San Francisco.

Something else awaited Eleanor in San Francisco: a job. Madge Carr Cook, whose claim to critical and popular success was soon to come in the title role of a play called “Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch,” had persuaded the owner of the stock theatrical company for which she worked to hire her 17-year-old, fledgling-actress daughter. Daniel Frawley paid her $15 a week.

But one month later, a series of events catapulted Eleanor to center stage: First, the company’s leading ingenue resigned unexpectedly, and then her replacement became seriously ill. By that time, the entire company was in Hawaii, engaged to perform a repertory of 13 plays. The ingenue roles fell to Eleanor, and that meant learning parts in 11 of those plays in no time flat. Eleanor rose to the occasion, Daniel Frawley rewarded her with a $20-a-week raise, and Eleanor traveled with the company to its next destination, Milwaukee. Two years later, she joined a Chicago-based company whose top-flight cast included Lionel Barrymore.

By the time Eleanor made her New York debut in 1900—she was 22 and commanded a salary of $150 a week—she had cut her teeth in a variety of roles. She played a Civil War rebel in “Held by Night”; Jane Eyre; and Bonita in “Arizona.” In New York, she added Shakespeare’s Juliet to her credits. Eleanor’s style contrasted sharply with the tradition of exaggerated gesture and stylized delivery that had come to be immortalized by Sarah Bernhardt. “Blood and thunder” held no appeal for Eleanor Robson. Her presence was more natural, and her ideal was the Italian actress Eleanora Duse, who had created a sensation by appearing onstage sans makeup.

In 1903, the respected British playwright Israel Zangwill asked Eleanor to portray the lead character in “Merely Mary Ann,” a play he was adapting from a story he had written. Eleanor consented eagerly, and her performance as the servant girl Mary Ann captivated audiences in America and Britain. One new fan was George Bernard Shaw, who wrote to Eleanor:

“I have just seen Mary Anne and I am forever yours devotedly. I take no interest in mere females; but I love all artists. They belong to me in the most sacred way; and you are an artist.”

Shaw wrote “Major Barbara” for Eleanor, but contractual obligations prevented her from performing in it. Their mutual admiration, however, continued, and they remained lifelong correspondents.

By the summer of 1908, when she was 29, Eleanor Robson’s career was in full blossom, but she found herself “worried, depressed, (and) irresolute” about her future. She had met a widower 26 years her senior, a multimillionaire named August Belmont Jr., who had proposed marriage. To marry Belmont would mean abandoning her career. To pursue her career would mean losing him. Those were her choices. For Eleanor, “either route involved a serious sacrifice. This ‘To be or not to be’ was not of easy solution.”

Her ardent suitor was one of society’s most eligible bachelors. He had grown children; he owned racehorses, yachts, and a railroad car staffed with a French chef. His father had established a banking house, August Belmont & Co, which represented the House of Rothschild in America, and when August Belmont Jr. finished his studies at Harvard, he joined the bank. Upon his father’s death in 1890, he became head of the company. August Belmont Jr.’s interests extended far beyond the world of banking: He founded the company that constructed the Interborough Rapid Transit Subway in New York City, he built the Cape Cod Canal, and he helped finance the crucial development of stabilizers for aircraft. He had an enormous sense of civic duty, and one of his many endeavors in that realm was to help secure the passage of the Workmen’s Compensation bill in New York State. Politically, he was a staunch Democrat, though many of his close friends— including Theodore Roosevelt— were not. His cultural interests ranged from the Metropolitan Opera (he served on its board of directors) to the New Theatre (he was a founder). And he was an avid sportsman. His father had established the Belmont Race Track at the Jerome Park Race Course, and August Belmont Jr. carried on the tradition, founding the American Jockey Club as well as hunting and polo clubs.

For two years, Eleanor wrestled with her dilemma. She thought about those who had invested much in her career: her mother, her business manager, a writer at work on a play for her. And she contemplated her own future happiness. At last, she reached her decision.

In February 1910, on a Brooklyn stage, Eleanor Robson gave her final performance as a Cockney waif named Glad in a runaway hit, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s “The Dawn of a Tomorrow.” She and the entire cast wept all the way through the play, right up to her last line: “I’m going to be took care of now.”

She married August Belmont two weeks later at her home at 302 W. 77th St. in New York City.

After their wedding, the couple yachted in the Mediterranean for two months, and when they returned, Eleanor plunged into an entirely new role: that of mistress of two houses, as well as a bungalow, a cottage, a shooting place, a six-story mansion, and a beach estate. These Belmont homes spread from Long Island to Kentucky, Saratoga, South Carolina, New York City, and Newport, Rhode Island. “It was a new world,” Eleanor recorded, and initially, “the innumerable details necessary to smooth administration in this department oppressed me.”

But Eleanor met the challenge with grace . . . and wit. In commenting about the private railroad car in which the Belmonts traveled, she said, this is “not an acquired taste—one takes to it immediately.”

August Belmont was an opera buff, and it must have been with supreme pleasure that his bride took her place beside him as hostess in Box Four in the Diamond Horseshoe at the Metropolitan. Eleanor’s first visit to the opera, six years before her marriage, had been a mad dash during an intermission of “Merely Mary Ann” to hear the third act of “Gotterdammerung.” She had stood in the wings then and had seen only a portion of the opera, but she had been enthralled and remained so.

Eleanor came to share another love of her husband’s—horses. Scarlet and maroon were the Belmont colors, and they festooned the Belmont Park racetrack as well as the Belmont Stud Farm in Kentucky. Eleanor took pleasure in naming many of the foals, including the most famous racing stallion of its era, Man o’ War.

Man o’ War was sold, though, before he reached his prime. Late in 1917, August Belmont decided to reduce the size of his stables. The United States had entered World War I, and Belmont was commissioned a major in the Government Remount Service with orders to report to Paris.

There were other changes during those war years: Eleanor began volunteer work with the American Red Cross, taking to the speaker’s platform to raise money and finding a new outlet for her talent and training as an actress. In the spring of 1917, she delivered 45 speeches in 38 cities and 10 states; in the fall she sailed for France to inspect U.S. Army camps and to report on Red Cross activities at the front. She carried a letter of introduction that began:

“My dear General Pershing: This is to introduce a most valued and most charming friend . . . Mrs. Belmont is one of the few really able people who are also gifted with the power of expression . . . She has a man’s understanding, a woman’s sympathy, and a sense of honor and gift of expression such as are possessed by very, very few either among men or women.”

It was signed, “Faithfully yours, Theodore Roosevelt.”

Her dynamic energy and hard work helped the Red Cross top the $100 million goal set for its first drive. August Belmont said he wished he knew of some eight-hour Workmen’s law that might include his wife.

August Belmont died in 1924 and was buried on his wife’s 46th birthday, thus ending another period of Eleanor Robson Belmont’s life. During their 14 years together, her husband had trained her well. “If you want a thing done, go,” he said. “If not—send.” Eleanor Belmont continued to “go.” She remained devoted to her stepchildren, and step-grandchildren, and to an ever-widening circle of friends. And she remained active in volunteer work and outspoken on public issues.

Convinced—as were many—that the Eighteenth Amendment, which instituted Prohibition, was a fiasco, she wrote a speech in which she declared:

“You cannot change the habits of a people by legislation. Only education can do that. We must take human nature as we find it.”

But she did not stop there. When she delivered the speech before the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, the year was 1931 and the Depression was at its height. She minced no words:

“Personally, I consider it a disgrace that today, when the world is facing great problems of economic adjustment that may even in a few years shatter this thing we call peace, when we ourselves are in the midst of a national crisis of unemployment, the most important political question is Prohibition.”

From 1931 through 1934, Eleanor Belmont devoted her organizing talents to the Women’s Division of the Emergency Unemployment Relief Committee. As its chairman, she spearheaded a two-month fundraising appeal for New York’s unemployed women. The goal was $500,000, a sum that would create jobs for 1,000 single women at $18 a week. Though her counsel suggested that $350,000 was a more realistic goal, she and her workers raised $597,000. A second fundraising campaign under her guidance, conducted during the winter of 1931, marshaled $4 million. Her approach was to directly solicit bankers and large business concerns.

While she worked on behalf of the city’s unemployed, Eleanor Belmont continued her work for the Red Cross. As a programming and policymaker for both organizations, she wielded much influence, serving as facilitator and liaison between the two groups.

In May 1933, she resigned her chairmanship of the Relief Committee and again went public with a strong conviction:

“If you will permit me, I will be absolutely frank . . . The major portion of the relief program should be assigned to the city, state or federal government, and the amount agreed upon . . . as necessary to carry out an adequate program, should be obtained by special taxation.”

Eleanor Robson Belmont’s vision of a democratic society extended even beyond the guarantees of employment, food, and medical care. It extended to participation in the arts and culture of society.

As the first woman appointed (in 1933) to the board of directors of the Metropolitan Opera, she conceived a group that held no class bounds of privilege or wealth, a group that could simultaneously help the opera and benefit from it. She founded the Metropolitan Opera Guild in 1935, and, over the years, it came to serve as a model for many regional opera and ballet guilds. To build the guild and consolidate its strength, she used her theatrically trained voice over the radio to urge support. And again, she turned to the business community for contributions.

The results surpassed most observers’ expectations. Officials at the Metropolitan Opera credited Eleanor with keeping the company alive. When she discovered in 1940 that the old gold curtain at the opera was to be sold for $100, she quickly set into motion a more profitable plan: The 10-ton curtain was cut into hundreds of souvenir mementos and their sales brought in $11,000.

Eleanor Belmont was perhaps the archetypal guild member: She worked zealously for the opera while continuing to be inspired and delighted by it. She kept her box, second from the footlights, although in later years she sometimes reclined on a couch in the box or donated her seats to young, impoverished opera lovers.

In 1937, her affection for young people and for the Metropolitan’s future audiences prompted her to inaugurate the guild’s series of Student Performances; in 1952, she founded the Metropolitan National Council, which not only developed national support for the Met but also encouraged young talent through an auditions program; and in 1966, she donated $500,000 to underwrite the guild’s program of student matinees. She also was concerned with the guild’s elders, and she founded the Metropolitan Opera Employees’ Welfare Fund.

Eleanor’s enormous contributions were recognized with trays and medallions of silver and gold. They came from the opera, the Red Cross, the National Institute of Social Sciences, the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Association, and the Hundred Year Association. Yale University conferred an honorary Master of Arts degree and Columbia University topped that with a Doctor of Letters.

In 1957, when she was 78, her memoirs were published. The “Fabric of Memory,” her 302-page autobiography, serves not only as a gathering of anecdotes and reflections, but also as social history.

During her later years, Eleanor Belmont divided her time between her Fifth Avenue apartment overlooking Central Park and a home in Maine that looked down from a hillside to the boating town of Northeast Harbor. She continued her extensive correspondence and entertained quietly.

When Eleanor turned 90 in 1968, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller—who had known and admired her since his boyhood—wrote:

“Men have been paying tribute to Mrs. August Belmont for the better part of this century, beginning with George Bernard Shaw in the century’s first decade. Her beauty, wit, talent, and charm are legendary, from her days on the London stage as Eleanor Robson, when she captivated Shaw; to the half-century and more that she has ornamented the New York scene and changed it so profoundly for the better . . . Surely she must be one of the great salesmen of this century, as her fundraising activities for the Met, the Red Cross, the Community Service Society, and other causes amply testify. Above all, however, she is a great lady—a truly fabulous and wonderful woman, one whose personal example and human concern for others set a standard we must not lose. Knowing her is a rare privilege.”

In 1923, Eleanor Belmont was appointed to the first Distribution Committee of The New York Community Trust. She served for more than 30 years. In 1965, she established in The Trust a Fund to benefit her special charitable concerns—social welfare, medical services, and, of course, the opera. The Eleanor Robson Belmont Fund was created by her will, and since her death in 1979, it has begun its work of perpetuating and extending those philanthropic interests.

On Jan. 10, 1979, 1,500 people attended an Opera Guild luncheon honoring Eleanor Belmont’s 100th birthday. A slide presentation documented the activities and accomplishments of her life, and Metropolitan Opera Association President Frank Taplin declared:

“Eleanor Robson Belmont . . . a magic name and a magic lady! She has encouraged us to think beyond our narrow times and places. She has given us a vision for the future.”

On October 24, 1979, she died quietly in her sleep in her Fifth Avenue apartment, age 100 years, 10 months and 11 days.

Eleanor Belmont’s sense of adventure, coupled with an enormous reservoir of energy, was never dulled by ease or affluence. Life bestowed riches on her, and she gave back to it generously.