Son of Texas family loved New York art and design. Fund at The Trust supports scholarships in the arts.

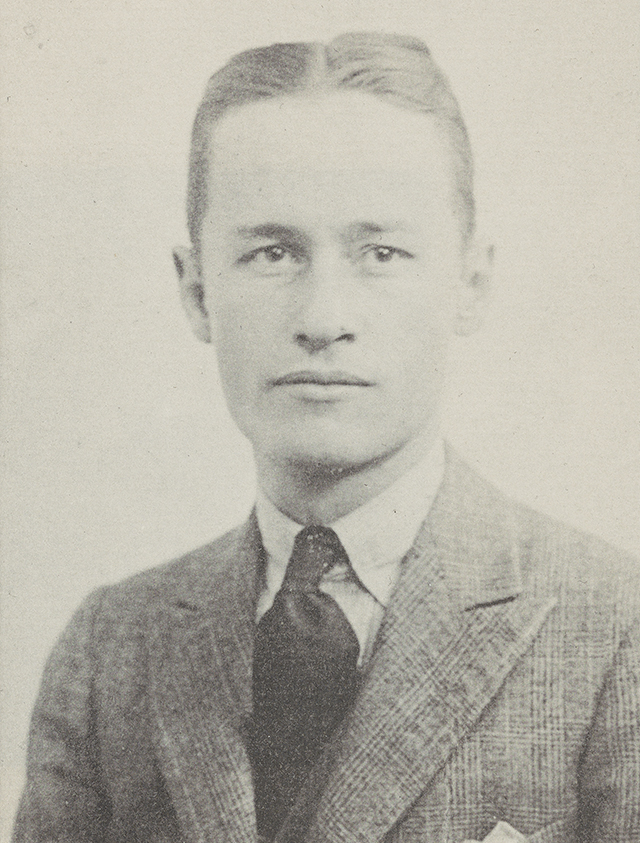

Edward Maverick (1901-1979)

Dear Emily,

Your cousin Edward is having the very time of his life. This is the most wonderful place and I want to stay here forever, so tell your Papa to bring you on over—My love to you and all your dolls—write to me some times and you’ll know I think of you lots.

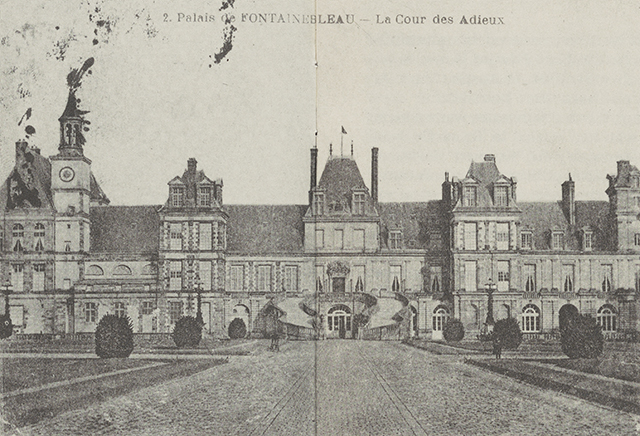

Edward House Sammons (who later changed his name to Edward Maverick) was 21 years old in 1923 when he sent that postcard to his cousin in Austin, Texas.

Emily Miller was only about 3 years old when she received it from her cousin Edward. So, she could scarcely share his appreciation for the splendid architectural achievements of 18th-century Europe he was learning about while enrolled in a special course at the Fontainebleau Palace in Paris.

However, Edward Maverick’s European studies made such a lasting impression on him that more than 50 years later, in his will, he established a scholarship fund to enable others to study abroad.

Edward was born on Oct. 31, 1901, in Austin, Texas. A brother, John, was born three years later.

Their father, Edward Sammons, was a native of New York who had settled in Texas. He was employed as secretary to “Colonel” Edward Mandell House, a Texas politician who was campaign manager and adviser to a succession of Texas governors. Colonel House, who became President Woodrow Wilson’s adviser and chief deputy, was Edward’s godfather and took a lifelong interest in him. When Edward moved to New York as a young man in the 1920s, Colonel House and his wife, Loulie, introduced him to friends and acquaintances, helping ease the adjustment.

Edward’s mother, a devout Christian Scientist, was a member of one of the most influential families in Texas. Known by everyone as Lillie, she was born Mary Agatha Maverick. Her Maverick ancestors had sailed from England to America in 1630, settling near what is now Chelsea, Massachusetts. Samuel Augustus Maverick Sr., her grandfather, a Yale-educated South Carolinian, settled in San Antonio, Texas, in the 1830s. He was a lawyer, businessman, landowner and, for nearly 30 years, a public official. He negotiated with Mexico for Texas’ independence, signed the Texas Declaration of Independence, and helped write the Lone Star Republic’s constitution. He was a mayor of San Antonio and a congressman of the Republic. After Texas joined the Union, he served as a state legislator. His biographers wrote that Samuel Maverick Sr. . . .

“. . . was called one of the ‘empire builders of Texas’ and, at his death, was said to be one of the largest landholders in the United States . . . He gave of his money and possessions to the city he loved and its citizens.”

Among Samuel Maverick Sr.’s many contributions to San Antonio were an orchard for a city park, several blocks of property to a church, and other property to encourage the growth of business. His children, too, made names for themselves in Texas politics and business. Edward’s grandfather, Samuel Maverick Jr., became a prominent businessman in San Antonio.

There was one other legacy from Samuel Maverick Sr. This one, however, was unwitting. The story goes that during one of his many trips away from San Antonio, Samuel Maverick left his cattle in the care of someone else. The cattle strayed and newborn calves were never branded. Soon local cattle herders came to recognize the unmarked cows; they were “Maverick’s.” Later, Texan cowboys driving cattle north to Montana helped popularize the term throughout the West. A “maverick,” according to Random House Dictionary, referred to “an unbranded calf, cow, or steer, especially an unbranded calf that is separated from its mother.” It also came to mean “a dissenter, as an intellectual, an artist, or a politician, who takes an independent stand apart from his associates.” As it turned out, there was a great deal of the maverick in Samuel’s great-grandson Edward House Sammons.

As a young boy, Edward stayed close to home, attending public schools in Austin and vacationing in San Antonio with his aunts and cousins at their homes near Maverick Park or at a family house called Sunshine Ranch. If the Sammons family travelled, it was usually only as far as to the Gulf Coast of Texas for holidays.

But not long after his graduation from the University of Texas, Edward began to test the waters outside the Lone Star State. His parents drove him to New Orleans and put him on a French boat sailing for Le Havre. It was his intention to spend a summer in France, enrolled in a course at the School of Fine Arts at Fontainebleau Palace, but when, at summer’s end, an opportunity arose to study at the French Academy at the Villa Medici in Rome, he seized it, and remained there for the entire year.

That year abroad cemented Edward’s professional interest in 18th-century interior design. The buildings he studied—and in which he studied—jewels of European period architecture, had enchanted him. When he returned to the United States, Edward, the family maverick, did not head for Texas but settled instead in New York City, where he became affiliated with a number of architectural firms as a special consultant in period design. He was never, according to one friend, involved “in things like air conditioning systems.” His interest focused on rooms: space in rooms, the detail in rooms, the formality of rooms. The appeal for him in 18th-century design was the Neoclassical sense of proportion.

During the 1920s, a number of wealthy Americans returned from trips abroad with furniture and furnishings to re-create 18th-century libraries and drawing rooms in their 19th- and 20th-century mansions. This type of project appealed to Edward, and he was hired to work on several. The Cape Cod home of Paul Mellon, the Long Island house of Paul D. Cravath, and the Texas home of Robert Welch Jr. all reflected his special touch. Perhaps the most interesting assignment of his career was “Hillwood,” the Washington, D.C., home of Marjorie Merriweather Post. She acquired the house in 1955 and then set out to remodel it. Edward worked on two of its rooms, a Louis XVI paneled living room, and a library with English paneling and 17th-century carving attributed to the Dutch-British wood carver Grinling Gibbons. Today, Hillwood Estate Museum & Garden is a decorative arts museum.

To learn even more about period design, Edward enrolled in courses at two British institutions, the Summer School of the Courtauld Institute of Art and the Attingham Park Summer School.

Founded in 1931, Courtauld is in a London town house designed and built by the 18th-century Neoclassical architect Robert Adam for Elizabeth, Countess of Home. Attingham is a country house built by Neoclassical architect George Steuart between 1783 and 1785. In 1952. it was leased by the British National Trust as a county college, and not long after, a summer program was established for the study of British history, architecture, and landscape. Edward augmented these studies with travel.

The stamps of Hungary, Austria, Germany, and France filled an early passport. He frequently returned to Europe, toured the Soviet Union twice, travelled throughout Central and Southeast Asia, to Indonesia and Japan.

He also loved music and had a fine tenor voice. He joined choirs, and in his early years in New York—during the Depression, when design jobs were difficult to come by—Edward supplemented his income by singing on the radio.

One family story has it that radio was what led him to change his name: The S’s in Sammons hissed. It’s hard to know whether that was the reason or whether, as another story goes, Edward felt very attached to the Maverick side of his family and was concerned that the name be perpetuated. (His Maverick cousins were all female, acquiring different names as they married.) Whatever the reason, in 1945, when he was 44, Edward House Sammons legally changed his name to Edward Maverick.

Although he never married, he was interested in young people and devoted to the younger members of the family. For example, when a young cousin passed through New York en route to Europe, Edward took the time to give her a definitive tour of the city. He also returned to Texas every few years to visit his family: His brother, John, had married, and Edward was very attached to John’s sons; also, some cousins still lived in San Antonio.

But the heat of Texas and the sweltering summers of New York didn’t appeal to him, so he spent much of the summer abroad. In town, he kept busy “eight nights out of seven,” according to one friend. He was a partygoer, often donning tails or tuxedo and attending the theater and opera. He also was an inveterate walker of the streets of Manhattan.

In New York, Edward’s first apartment was in the historic Colonnade Row on Lafayette Street between Astor Place and East Fourth. Later, he moved to a walk-up building farther uptown on the East Side. His last years were spent in an apartment he owned near the United Nations Plaza, a place filled with porcelains, paintings and furniture collected on trips abroad. Books, many of them rare, on fine art, art history, and architecture lined the shelves of his living room.

His politics were always Democrat—a Texas family inheritance. Also, according to his sister-in-law, it was the Democrats’ New Deal—specifically the Works Progress Administration (WPA)—that put Edward to work singing on the radio during the Depression, and he never forgot that. (The songs he sang on the radio were of the operetta style, and he mainly performed in French and Italian. Though his sister-in-law did not know specific titles, she did recall the name of an amusing American ditty he once sang to her in Texas. It was called “Peekin‘ Through the Knotholes on Grandpa’s Wooden Leg.” Edward, she recollected, had a good sense of humor.)

In his later years, Edward wrote to his cousin Emily—now a middle-aged woman—that he wondered “where all the good theatre has gone.” He attended fewer plays and more films, especially matinees. He watched public television and contributed to Channel 13 in New York. He had, as well, made contributions for years to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and was a member of the American Friends of Attingham and of the Society of Architectural Historians.

In about 1972, Edward’s health began to fail. He was diagnosed with cancer and underwent surgery. He concealed the true nature of his illness from family and friends until it had advanced so far it could no longer be kept a secret. Even then, although he suffered much pain, he rarely complained. Before he died in 1979, he gave his architecture books to the Architectural Library of the University of Texas. His collection of more than 8,700 slides, entrusted to a friend, were eventually donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1963, he had established in Community Funds Inc., the Edward Maverick Fund for scholarships to assist advanced students to study abroad, preferably working architects, interior designers, art historians or museum personnel.