From plowing the family farm to leading Colgate-Palmolive. His charitable legacy continues through a fund at The Trust.

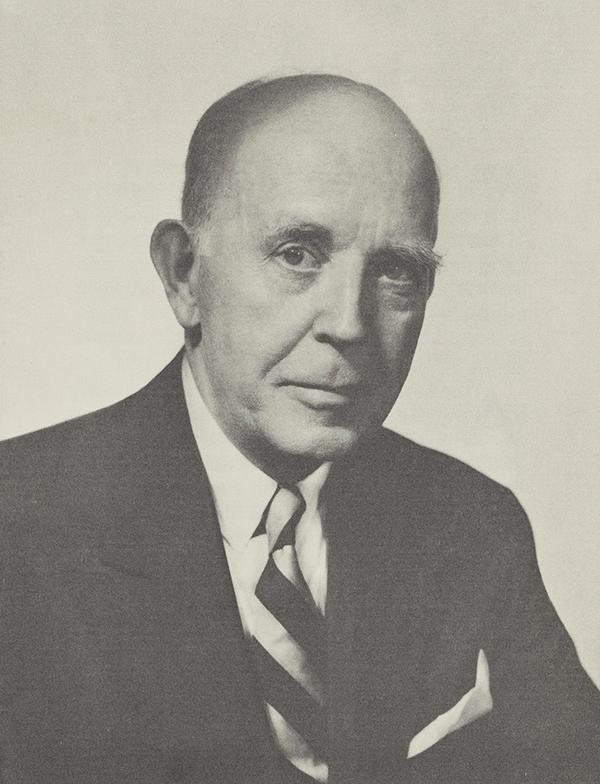

Edward H. Little (1881-1981)

In the early 1900s, Mecklenburg County outside Charlotte, North Carolina, was farming country—a patchwork of rolling hills, tobacco and cotton fields. For most of the people who earned their livelihoods from the land, farming was hard work, and the rewards were modest. Many families had been there for generations, but for those who were young, bright, and ambitious, Mecklenburg County—though a fine place to come from—was not the place to stay. One such individual was Edward Herman Little, who, in his own words, “was determined to make good.” His ambition, dedication, and belief in the integrity of his work propelled him from the rural South to the top of an international corporation—a corporation that experienced extraordinary growth under his leadership.

Edward Herman Little was born April 10, 1881, the fifth of 12 children of a cotton farmer, George W. Little, and his wife, Ella Elizabeth Howie Little. Home was a cotton plantation not far from Charlotte, and all the children were expected to do chores. Herman, as his family called him (to others he was Edward or E.H.), attended public schools in Mecklenburg with his brothers and sisters; he also attended Grey’s Academy in Huntersville, North Carolina.

George and Ella Little were devout Presbyterians and saw to it that their children received religious instruction. They sent their eldest son (E.H.’s brother) to college because they wanted him to become a minister. But that was an exception in the Little family—and a sacrifice, for George Little just managed to keep his farm going and his family clothed, fed, and sheltered.

By the time he was 14, Ed Little was an accomplished horseman. He competed in local tournaments modeled after medieval jousts. With a spear in one hand, the horseman rode at breakneck speed, piercing rings suspended from posts placed at intervals around a course. Young Edward nearly always won, but the reward—placing a crown on the head of a young girl chosen as “Queen”—so embarrassed him that he gladly relinquished the honor to other boys.

By the time he was 16, E.H. had decided to leave the farm. (Eighty years later, he remembered how he reached that decision: “I plowed with a mule so stubborn that when the dinner bell rang at midday, he would stop still. I had to take him home and feed him before he would work again. I got so tired of looking at the rear of that mule I was glad to get off the farm. I left when I was 17.”)

He left the farm in 1898 to take his first job. For room and board, plus $10 a month, he went to work for J.S. Withers, a Charlotte grocer who also happened to be the official elected cotton weigher for Mecklenburg County. Edward intended to learn enough to become a cotton broker, and he must have worked diligently, because he became known to a Charlotte businessman, Clarence “Booster” Kuester—who later became known locally as Charlotte’s Mr. Chamber of Commerce. In 1902, Kuester recommended Ed for a job traveling through the Carolinas for Colgate & Co., selling Octagon soap and toilet articles. Ed took the job and quickly proved to be a skilled salesman. He traveled from town to town in a horse and buggy, and in each community, he hired young boys to distribute soap samples and premium lists door to door. Since some of the soap wrappers could be redeemed for Colgate products, Ed would then go to store owners, inform them that customers would be coming to purchase the products … and sell a supply.

Four years after he began selling for Colgate, Ed Little’s sales manager beckoned him to New York to attend a special meeting on Colgate’s 100th anniversary. The year was 1906. When he got there, he received a promotion and was sent to Memphis as the new district manager for Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi.

The 25-year-old country boy checked into one of Memphis’ finest hotels, the Gayoso. His room was his base; from there, he traveled by train to sell Colgate products throughout his new territory. His professional life was booming. And so, too, was his personal life.

Suzanne Trezevant was a debutante who came from an aristocratic family of Memphis attorneys and judges. She and Ed Little met, and soon he began courting her.

At about the time it was becoming apparent to their friends and families that Edward and Suzanne were in love, Suzanne’s mother said to her, privately, “If you think much of your young man, you had better send him to a doctor about that cough.”

“That cough”—a persistent one—was tuberculosis, Ed’s doctors told him, and the only effective prescription was complete rest. The location: a facility in Denver, Colorado.

In 1910, Ed Little resigned from Colgate, left Memphis, and arrived in Denver. Suzanne followed him there in time for Thanksgiving, and they were married immediately, on November 24. Edward was 29. It took him more than three years to regain his health. His full recovery, he insisted, was all because of Suzanne. “For three years,” he said years later, “she left me only twice for as long as 30 minutes—once to see a friend and once for a crochet lesson.” That was not all he attributed to his wife. “She was,” he went on, “the most beautiful, the most talented, the most courageous. Without her, I would not have lived, and I would never have achieved anything.”

It was Suzanne who saw an advertisement in a Denver newspaper for a new soap. It was called Palmolive and had been developed by the B.J. Johnson Soap Co. She encouraged her husband to apply for a job. Bolstered by her confidence in him, he sent in an application. He got the job, and in January 1914—3 ½ years after he arrived in Denver seriously ill—he began selling Palmolive soap in an area west of the city. One year later, he was made district sales manager for the Pacific Coast, and he and Suzanne moved to Los Angeles. In 1917, the B.J. Johnson Co. became the Palmolive Co. At that time, Ed Little was one of eight district managers working for the company, and his sales routinely led the others. According to E.H., there was “this one fellow, always at the bottom, who rationalized that somebody had to be at the bottom, and my reply was, ‘Not me!’ ”

In 1919, E.H. was appointed district manager for New York, and he and Suzanne moved east. In 1922, at age 41, he brought home $60,000 for the year—$10,000 in salary and $50,000 as his share of corporate profits. Two more promotions quickly followed. In 1926, the Palmolive Co. acquired Peet Brothers and became known as the Palmolive-Peet Co. E.H. was appointed general manager of foreign sales and advertising, with headquarters in Paris. In less than two years, he developed markets in every European country and bought a soap factory in Germany. His efforts more than doubled Palmolive-Peet’s business and paved the way for its merger in 1928 with the Colgate Co.—the same company Ed Little had worked for 20 years earlier.

In 1933, E.H. was elected vice president of the Colgate-Palmolive-Peet Co., in charge of sales and advertising.

Five years later, he was elected president of the company. He was 57. The year was 1938, and the Depression was still on. He served as president for 15 years, until 1953, when he became chairman of the board. From 1953 to 1960, he sometimes served as both president and chairman. He remained chairman until he retired at age 80.

E.H. Little’s accomplishments during nearly 60 years of service (22 of them as head of the company) were impressive. Annual sales stood at $100 million the year he became president; when he retired, they had climbed to $600 million. During that period, company plants in the United States and overseas were expanded and modernized. E.H. Little had guessed correctly that the demand for soap and toilet articles would increase after World War II.

As head of the company, his approach to advertising was aggressive. He was personally involved in negotiations to assure Colgate-Palmolive’s visibility during the early days of television. The result was “The Colgate Comedy Hour,” a prime-time Sunday evening program that showcased entertainers like Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin, Jimmy Durante, and Ed Sullivan.

In 1938, his first year as president, E.H. visited a company plant in New Jersey to wish his employees a Merry Christmas. He came away determined to do something more for them, and, within a year, he had begun to institute changes. A pension plan was adopted for all employees, and benefits were added several times over the years. Subsequently, life insurance coverage was increased, a hospitalization plan was adopted, and a savings and investment plan for employees was approved by stockholders.

While Little was head of the company, the number of employees nearly tripled, from 9,600 to 26,000.

Although E.H. Little did well for, and by, Colgate-Palmolive, he maintained publicly that money was never his driving ambition. “I would have made more if I’d been more interested in money,” he explained. “But I was interested in building up the company, and that’s what I worked for. It just so happened that while I was building up the company, a lot of money was being made.”

E.H. once said the secret of his success was simple: “I told people, ‘Take a bath, get your clothes clean.’ ” He was only half-joking, for Ed Little had faith in the value of the products he sold. He also had persistence. If a potential customer did not buy his products, Salesman Little would go back and ask what he had done wrong. He summed up his philosophy about work this way: “I was determined to make good. I always believed in work and that you could do whatever you were determined to do. I liked to take on tough jobs.”

When E.H. and Suzanne moved to New York in 1938, they made their home in the Ambassador Hotel on Park Avenue at 51st Street. Since Colgate-Palmolive’s headquarters was in Jersey City, E.H. commuted from Manhattan to New Jersey by chauffeured limousine. During summers in the ’30s and early ’40s, he and Suzanne escaped the city’s sweltering heat and stayed at the Hotel Montclair in Montclair, New Jersey. And very August, they visited a health spa in Battle Creek, Michigan. E.H.’s bout with tuberculosis had convinced him he had to take special care of his health, and, for the rest of his life, he did. If he felt a cold coming on, he stayed home and made phone calls from there. He carefully watched his diet. And he refused to allow himself to be pressured: If an advertising agency executive wanted a decision immediately after a presentation, E.H. was likely to respond, “Let me sleep on that one, young man.”

His manner was dignified: He stood about 6 feet tall and erect. His suits were custom-tailored. His voice bore traces of his Southern accent. He was fair with those who worked for him, but, as one employee put it, “He demanded a full day’s work for a full day’s wages.” He expected no more of them than he did of himself: complete dedication to the company and an intrinsic belief in the company’s products. He commanded respect, and to everyone at Colgate-Palmolive (except two older senior executives), he was “Mr. Little.” E.H. Little enjoyed the respect he was shown.

Though Ed Little lived in New York City for 40 years, he always considered himself a Southerner. “Home” was Charlotte and Mecklenburg. Once, when the company limousine broke down near the Holland Tunnel, E.H. hailed a taxi. As the cab headed toward Colgate-Palmolive headquarters in New Jersey, E.H. began to chat with the driver and discovered that he, too, had been born in Mecklenburg County. When they arrived at Colgate-Palmolive, E.H. who was carrying no money, asked the driver to come in. When the driver left, he carried away not only his fare and a generous tip, but two large boxes of Colgate- Palmolive samples.

As E.H. Little’s fortune increased—and since he and Suzanne had no children—he devoted much time and interest to philanthropic activities. Again, his heart was in the South. He developed a special interest in Davidson College in North Carolina (where his eldest brother had been educated) and donated, by his estimate, nearly $2 million. Davidson awarded E.H. Little an honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 1953 and dedicated the Edward H. Little Dormitory in 1957. He later provided half the financing for the college library, which also was named after him. The man who never attended college contributed to 19 other colleges and universities in the South. He also gave generously to other Southern schools, including country and mountain schools for poor children. And he made donations to hospitals. In Memphis—his “second home” —he contributed to St. Jude’s Research Hospital and Le Bonheur Children’s Medical Center.

In 1964, Suzanne Trezevant Little died. E.H. maintained his New York apartment—by this time he had moved into the Waldorf Towers—but he began spending more time in the South—wintering in Naples, Florida, and visiting brothers and sisters and their families in Charlotte. One of the funds E.H. established in The New York Community Trust contributed $1 million for the construction of an Episcopal retirement home in Memphis. It was called Trezevant Manor—named after Suzanne—and after it was completed, he moved into one of the apartments.

E.H. kept busy with his philanthropies; in the last decade of his life, he donated a million dollars every year or so to various charities. And though he no longer had an executive position at Colgate-Palmolive, he still had a large block of stock. His interest in the company never waned. He attended the annual shareholders’ meetings and had every intention of attending the gathering on April 22, 1981—the year of his 100th birthday. In the end, he was too weak to make the trip.

Twelve days before, however, he had celebrated his 100th birthday at a party he had taken a great deal of time and pleasure in planning. “One hundred is a nice, round figure,” he told a visitor before the party. “If I had another 100 years, I’d still be an optimist. I’ve always believed that things were going to turn out all right—and they have.” When asked whom he had most admired throughout his life, he answered, Dale Carnegie and President Grover Cleveland. And when asked whom in his 100th year he most admired, he grinned and said, “E.H. Little.”

Guests came to E.H. Little’s 100th birthday party from New York and New Jersey, from North Carolina and even Europe. There were 141 in all, and they included Colgate-Palmolive executives and former associates, the president of Davidson College, Memphis businessmen and educators, friends and family. The Champagne flowed as toast followed toast.

In one testimonial, the chairman of the Distribution Committee of The New York Community Trust said: “Giving away money well is almost as hard as making it. It is not just handing out $1 here and $10 there; it is making an investment in the future of mankind. E.H. has treated it as such.

“The word ‘philanthropy’ comes from the Greek words ‘philos,’ meaning friend, and ‘Anthropos,’ meaning man. I give you Edward H. Little, superb philanthropist and friend of man.”

Three months later, on July 12, 1981, E.H. Little died.

At his death, he reportedly left more than $3 million in direct charitable bequests. The rest of his estate went to create a fund at The New York Community Trust to benefit many of the same institutions he had supported so generously during his lifetime.