Dedicated Public Servant, Educator, and Mentor

Dr. James R. Dumpson (1909-2012)

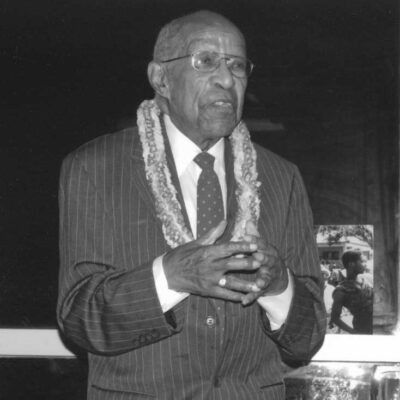

For his 100th birthday in 2009, James R. Dumpson was honored at four celebratory events that paid tribute to his career and accomplishments. Each event recognized the distinct but intersecting strands of his professional life: the field of social work, public service, academia—and the religious faith that informed all his endeavors.

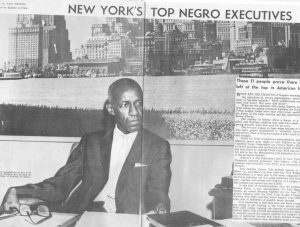

A powerful advocate for the poor, an influential public administrator, a beloved mentor and educator, Dumpson was often referred to as a trailblazer. As commissioner of welfare for the City of New York from 1959 to 1965, he was the first African-American—and the first social worker—to hold that office. And in 1967, he was named dean of the Graduate School of Social Service at Fordham University, the first African-American to lead that program. Fordham later named an endowed chair in Child Welfare Studies after him.

During his 65-year career, Dumpson held prominent positions in the administrations of five New York City mayors, from Robert F. Wagner, Jr. to David N. Dinkins. He was known as an effective voice for policy reform and a skilled, politically astute administrator who knew how to get things done.

His policy work also had a national and international reach. In the 1950s, as an advisor to the United Nations on Child and Family Welfare, Dumpson traveled to Pakistan to help design social work education programs and social services for youth. In the 1960s, he was appointed by President John F. Kennedy and by President Lyndon B. Johnson to policy advisory commissions addressing problems of substance abuse.

Dumpson returned to Asia several times as a consultant for various agencies, including trips to South Vietnam after the Vietnam War to start a program that trained social work graduate students to help refugees who had fled to Thailand. During his two terms as president of the National Council on Social Work Education, he collaborated on other national and international projects.

Dumpson was most dedicated, however, to helping the neediest in New York City and to strengthening the teaching and practice of social work, which he saw as a critical agent for change. His public service was fueled by a lifelong commitment to promote a more just, equitable, and caring society.

“Dr. Dumpson’s strongest identification was with the field of social work, and that was the integrating theme: this concept of social justice, his concern for vulnerable, at-risk populations,” said Alma Carten, associate professor at New York University Silver School of Social Work and the author of an upcoming book on Dumpson’s professional papers. “He felt that social work had a major responsibility to keep society on a morally correct path.”

Early Years

James Russell Dumpson was born on April 5, 1909 in Philadelphia, the oldest of five children. His father, James Dumpson, was a bank messenger and his mother, Edyth, had been a teacher before her marriage. Dumpson financed his college education by working summers as a hotel waiter in Cape May, New Jersey, and teaching in a segregated public school in Oxford, Pennsylvania. He attended State Teachers College at Cheyney University, a historically black university, and the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work.

His first job in the field was as a caseworker for Philadelphia’s Department of Public Welfare, shortly after the passage of the 1935 Social Security Act. Dumpson worked in poor communities to qualify families for the Aid to Dependent Children program. In 1940, he took a job with the New York Children’s Aid Society, developing a division to better address the needs of black children, who had been ill-served by segregated child welfare agencies.

During this time, Dumpson earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in sociology from the New School for Social Research. He later received a Ph.D from the University of Dhaka in East Pakistan.

Family Life

In the early 1940’s, Dumpson married Goldie Brangman, a nursing student who went on to co-found the School of Anesthesia at Harlem Hospital, where she worked until her retirement. While the couple remained close, they mostly lived apart, maintaining separate apartments on the same Manhattan block. Their only child, daughter Jeree Wade, recalls a happy childhood spent between the two homes. “They were beautiful parents,” she said. “I never heard an unkind word from them—between or about each other or about anybody else.”

Wade is a life coach and performing artist who often celebrates her father in her work. She cherishes memories of the two of them spending time together when she was a girl. “Since we didn’t see each other every day, it was always very special being with him,” she said. “My mother would dress me up and he would take me in his Chevrolet wherever he had to go, particularly to church. We shared many wonderful moments; the whole family was full of laughter. But this is what I remember most.”

Guided By His Faith

Dumpson was raised Episcopalian, at a time when congregations were segregated. When he tried to attend services as a young teacher in rural Pennsylvania, he was turned away by the all-white Episcopalian church. The local Catholic church was more welcoming and invited Dumpson to join the congregation. That experience, and his subsequent exploration of Catholicism, led him to convert, and several of his siblings did the same. His brother Roland became a Catholic priest.

Dumpson’s religious faith shaped his commitment to public service. “It was the bedrock of his belief that it’s not enough to accomplish for yourself—you have a responsibility to help others, particularly the neediest among us,” said Dr. Billy Jones, a former president of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation and commissioner of the Department of Mental Health.

While he was a devout Catholic, Dumpson criticized church dogmas that he felt were harmful to the poor and vulnerable. For example, he advocated for women on welfare to have access to contraceptives. Later in life, he served on the Black Leadership Commission on AIDS, promoting policies responsive to the devastating impact of HIV/AIDS in African-American communities.

“Jim saw enormous change in his lifetime and he was able to keep up with the changes,” said Jane Stern, a friend and former colleague at The New York Community Trust. “He was not stuck in the past. He always had an open mind and could take on new issues.”

A Powerful Voice

Dumpson experienced fluctuations in support for social welfare policies. He gained prominence when government spending increased in the 1960s and ’70s, and he continued to champion a more caring society in later decades, as politicians became skeptical of the concept of a social safety net.

“Jim was always a voice that would be heard and listened to, even if people didn’t agree with him. He was measured, never extreme, and always provided substantive documentation,” said Dr. Billy Jones. “He helped to set a higher level of policy debate and discussion.”

Dumpson never hesitated to speak out when policies he believed in came under attack. To critics who questioned the character of welfare recipients, Dumpson replied that with very few exceptions people on public assistance, particularly children, desperately needed the support. He argued that every adult would rather work and that most considered having a job an essential element of personal dignity.

“There’s no comfort living on a subsistence level,” he noted in the 1960s. “There’s no comfort in constantly having to establish eligibility. No comfort in the necessary intrusions into your private life to find out if you qualify for assistance.”

Dumpson also worked to combat welfare fraud. In 1975, as head of the City’s Human Resources Administration, he set up a computer system that eliminated several thousand recipients who were also receiving paychecks or unemployment benefits.

A Lifelong Optimist

One of Dumpson’s defining characteristics was his belief in positive change. “You’ve always got to hold on to the great potential for change that people have,” he once said. “And when you see that change—that’s what keeps social workers from being overwhelmed by the misery around us.” Dumpson’s friends describe his basic civility—he never spoke badly of others, even critics who publicly attacked his policy positions.

Edward Mullen, professor emeritus of social work at Columbia University, who considered Dumpson a key mentor and close friend, noted that all his actions were guided by the same core values. “Jim did not compartmentalize his personal and professional lives—they meshed seamlessly.”

By all accounts, Dumpson’s personal style was warm, kind, gentlemanly, and urbane. An engaging conversationalist and a meticulous dresser, he loved to entertain friends, family, and colleagues at his elegant apartment in upper Manhattan and, for many years, at his house in Westhampton, Long Island. Even on hot summer days or when traveling in sub-Saharan Africa, he wore a suit. “I never once saw him in shirt sleeves,” a former colleague noted. Yet, when he was close to 90, Dumpson thought nothing of riding around Shelter Island on the back of his grandnephew’s moped.

One of his passions was music—particularly classical, opera, and sacred music. For years Dumpson had season tickets to the Metropolitan Opera and he would relax at home by listening to opera broadcasts on the radio. His apartment was filled with photos that documented his friendships with political and civic leaders. “It was like a history of the United States,” a friend observed.

Mentor to Many

While he was modest about his own accomplishments, Dumpson encouraged the many people he mentored to claim their own. “He was small in stature but huge in terms of his impact and his ability to make you feel like you were the only person in the room when he was talking to you,” said Peter Vaughan, former dean of Fordham’s School of Social Service.

Dumpson believed in bringing people together to solve problems, and that diversity enriched the enjoyment of life. His grandnephew, Donald Dumpson, a musician and composer who was close to his uncle in later years, credits this attitude with transforming his own views.

“The biggest learning curve for me was Uncle James’ perspective on race dynamics, which can be so complicated. Here was someone who was born when he was born and came up through what he came up through and yet always had an optimism, a sense of the possible, that we can all help make a difference. It was so inspiring to know that despite what society can sometimes bring forth in terms of race, there’s hope, people do care, and change can happen.”

In 1973, Dumpson was a founding member of Black Agency Executives, an organization of human service and nonprofit leaders in New York City. He joined agency delegations on several international trips that explored social welfare policies in other countries, and he remained an enthusiastic traveler into his 90s.

Dumpson also served on many advisory committees and boards, including the United Way, Emergency Alliance on Homeless Families, Community Service Society of New York, and Associated Black Charities of New York.

In addition to Fordham University, Dumpson taught at Hunter College School of Social Work and several other universities. He wrote articles that examined a range of social welfare issues. He coauthored, with Edward Mullen, the seminal book on social work education reform, Evaluation of Social Intervention, published in 1972, that was based on a national conference the two had organized at Fordham University.

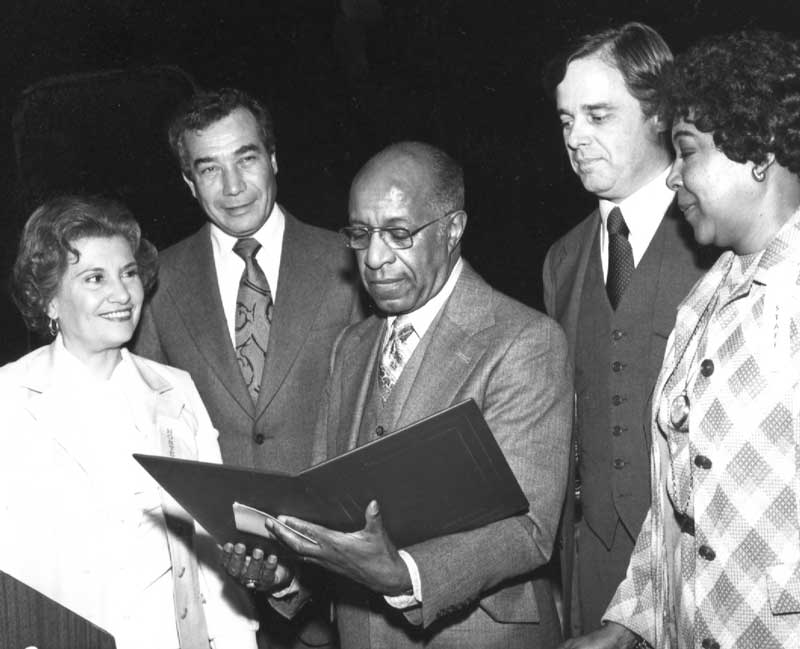

Dumpson’s work earned him widespread recognition. Among his awards: five honorary academic degrees; the Keystone Award for Distinguished Service in Social Welfare, from the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies; the Distinguished Service Medal from the Council on Social Work Education; Honorary Lifetime Member of the Institute of Social Sciences; and Fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine. In 2000, Dumpson was honored by the government of Ghana, which bestowed the royal title of “Nana,” and named a new library after him.

Not Quite Retired

When Dumpson’s wife retired from Harlem Hospital in the early 1980s, she decided to move to Hawaii. The couple bought a home in Honolulu, which Dumpson, his daughter, son-in-law, and various cousins would visit. It became a tradition for the family to spend Christmas and a month in the summer there.

In semi-retirement, at the age of 81, Dumpson was called back to public service. Mayor Dinkins appointed him health services administrator and chairman of the board of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation. He also lectured as a visiting professor at Fordham University and served as a senior consultant with The New York Community Trust, where he worked into his early 90s. At The Trust, Dumpson supported research and programs that benefited the elderly, particularly from poor communities, and he helped create the New York Center for Policy on Aging.

As a nonagenarian, Dumpson continued to meet regularly with former colleagues. “Because he enjoyed and sought out individuals with diverse backgrounds and points of view, he maintained a vital intellectual life, even into his most senior years,” said Edward Mullen. Noted Pat White, a program director at The Trust: “Dr. Dumpson was always ‘on’ intellectually. There were moments you could engage in a conversation with him as if he were much younger, he was so sharp and on point and current.”

When Dumpson began to experience short-term memory loss in later years, he gave a name to the problem: Dr. Sieve. If he asked friends to repeat something, he would say: “Dr. Sieve is working. Now what did you just say?”

Peter Vaughan, the former dean at Fordham, devised a way to continue to consult with Dumpson. “I would call and say I’d like to talk to you about a few things, and give him a date that I would call back to discuss these issues, so he had time to gather his thoughts. He would carefully write down my questions on that page in the calendar. When I called back, he always had his responses written down and we would have a really good conversation.”

A few years before Dumpson’s death, Vaughan and his wife drove him to a Black Agency Executives picnic on Long Island. Many of the participants had been Dumpson’s students or colleagues. “I wasn’t sure how it would go. He walked in and people rushed to greet him,” Vaughan said. “While he didn’t remember names, he did remember faces, and he remembered specific things about people’s professional accomplishments that he acknowledged. So each person he spoke with walked away feeling good. That’s the kind of person he was.”

Dumpson’s daughter and son-in-law bought their house in New Jersey with the idea that he would come to live with them when he needed more constant care. But a few days after moving in, Dumpson missed his Manhattan apartment and decided to move back. Wade hired and managed a staff of caretakers, which allowed Dumpson to remain at home until the end. James Dumpson died of a stroke on November 5, 2012, at the age of 103.

Celebrating a Life

Dumpson’s 100th birthday celebrations in 2009 stretched over four months, and reflected his iconic status among several generations of social-work professionals and City leaders. At its annual Martin Luther King Jr. luncheon, attended by more than 500 guests, Black Agency Executives honored Dumpson with a lifetime achievement award presented by former Mayor Dinkins. His leadership and dedication to public service was further recognized at a gathering hosted by the Office of Mayor Bloomberg and the City Human Resources Administration.

Dumpson’s strong faith was acknowledged with a special “Day of Praise” Mass at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola in Manhattan. The final public event celebrated his academic achievements. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture inaugurated a month-long exhibit that featured Dumpson’s scholarly writings and other materials that documented his contribution to critical social-welfare policies. Dumpson attended all but one event, which he missed because of a brief hospital stay.

The Trust marked Dumpson’s centennial by creating a special fund that supported the indexing and cataloguing of his papers. The James R. Dumpson Collection of writings and other records of his public life are now archived at Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service.

A tribute page on the Black Agency Executives website features a 1997 quote from Dumpson:

“Over my professional career, I have had the privilege of presenting my views on the dilemmas and challenges of our social welfare state. An enduring theme has predominated my message, which has been to stimulate people to consider and be willing to meet the challenge involved in creating a caring society for all Americans—a society distinguished by the equal treatment of all people, and it’s compassionate response to those least able to care for themselves.”

The James R. Dumpson Fund for Social Service, in The New York Community Trust, was set up by family, friends, and colleagues in 2009 to honor Dr. Dumpson’s commitment to the field. James Dumpson died of a stroke on November 5, 2012, at the age of 103.

In an obituary, the New York Times quoted former Mayor Dinkins, who had appointed Dumpson to two cabinet positions. Noting that Dumpson had influenced antipoverty policies for more than half a century, Dinkins said, “We don’t realize that history is being made until later,” He added, “We look back on it now and say, ‘Damn, he was a hell of a cat’—and indeed he was.”

The James R. Dumpson Fund for Social Service was set up by family, friends, and colleagues in 2009 as a field-of-interest fund to honor Dr. Dumpson’s commitment to the field.

The New York Community Trust is a community foundation, helping New Yorkers achieve their charitable goals and making grants that respond to the needs of our City.