A researcher and advocate for racial justice. Their fund at The Trust supports research into key social issues.

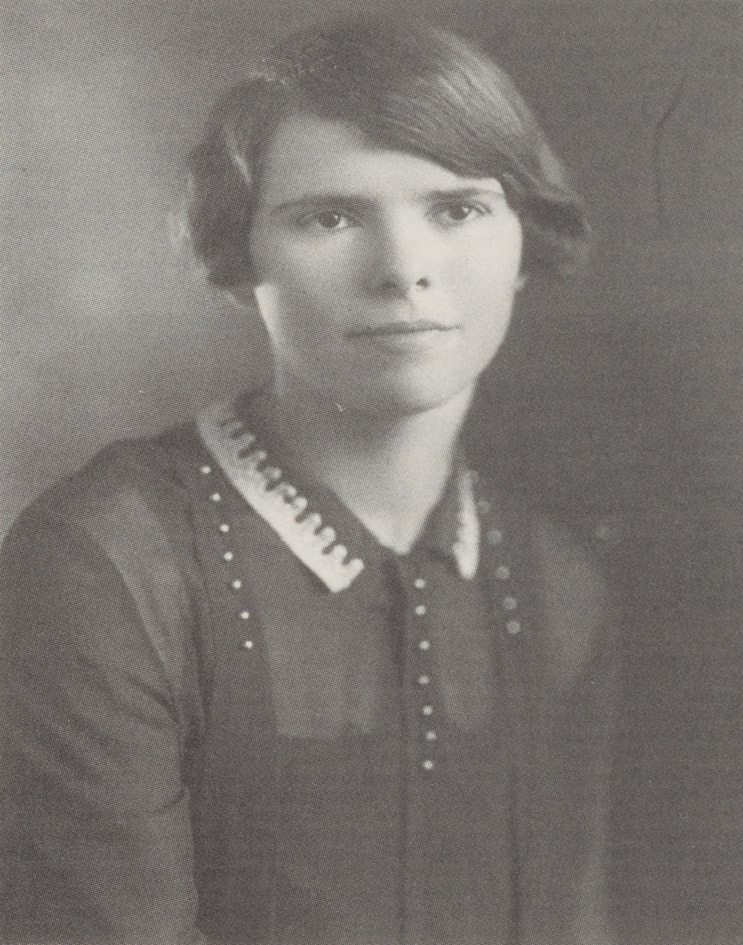

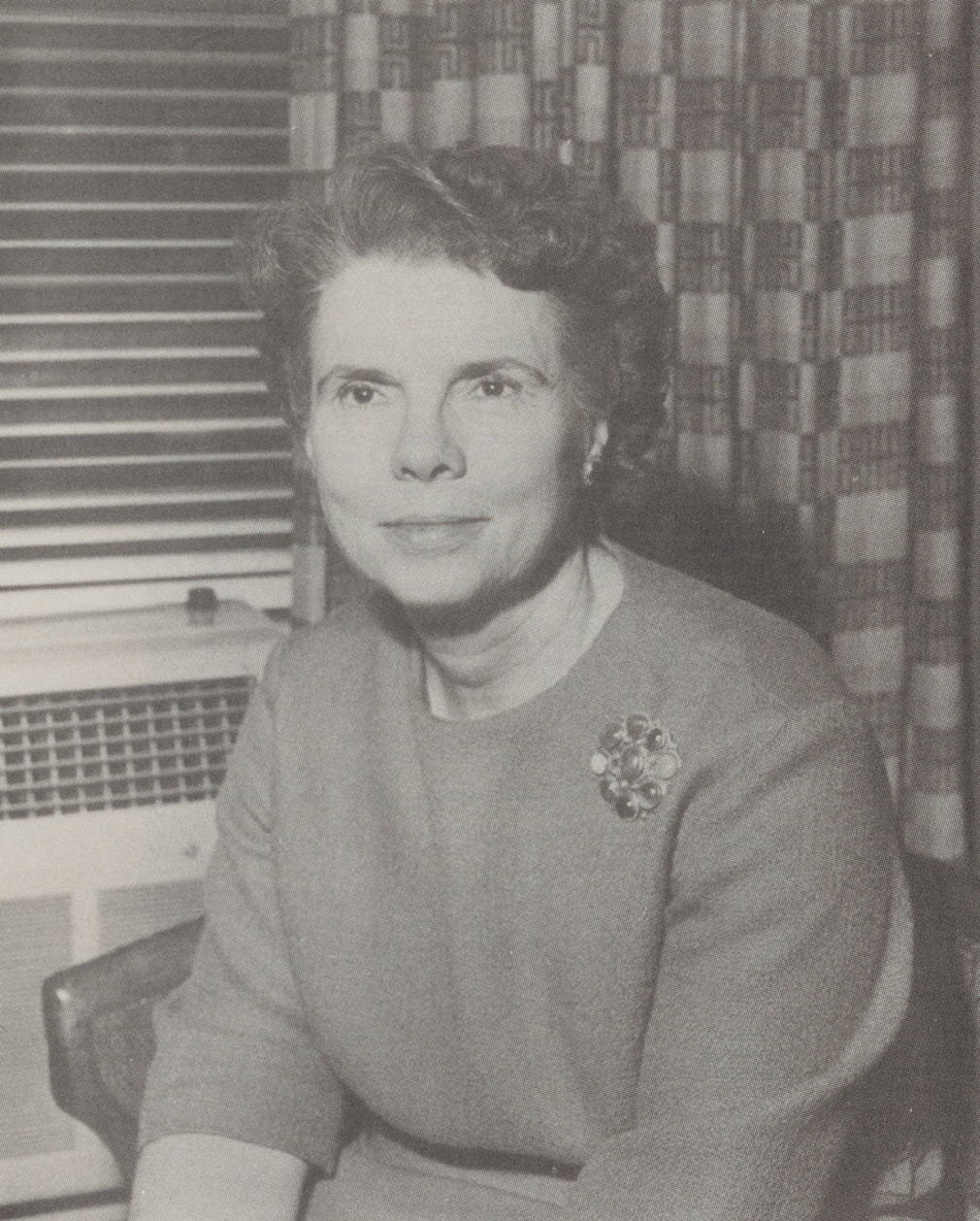

Dorothy Fahs Beck, PhD (1906-2000)

Hubert Park Beck, PhD (1907-1989)

Racial segregation was an accepted way of life in the American South of the 1920s when Dorothy Fahs arrived at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, a tradition-bound and very proper school for girls in Lynchburg, Virginia. Her doctors had recommended the college because the warm climate would help her recover from health problems. The 19-year-old freshman, coming from a socially progressive family, was appalled by the entrenched system of racial segregation and soon found a way to express her convictions. She won first prize in an essay contest sponsored by a regional interracial commission with an entry arguing that colleges needed to become more involved in eliminating racial prejudice.

“Racial conditions cannot be separated from life and treated in the abstract,” she wrote, insisting that they be examined by visiting the courts, prisons, schools, hospitals, and recreational centers. “Race relations are not solely an American problem,” she argued, “but a world problem.” She felt that students should not be indifferent to this “spirit-crushing struggle of class and race.”

“[T] he dean took it upon himself to announce the prize to the entire assembly of students, from which I had been keeping all of this secret . . . These surprised students wouldn’t understand how come I had chosen such a topic. And secondly, they all had to justify why it was they had to lynch Negroes in the South. So, after I had heard lots and lots of explanations of that, I was getting pretty fed up. And I decided I was going to experiment with the Jim Crow business.”

True to her beliefs, Dorothy was determined to put her rhetoric into practice. She would ride “Jim Crow” in the back of the bus, not up front with white passengers. With her skin darkened by cosmetics, Dorothy would board the bus and head for a rear seat. The ruse succeeded at first, but on a particularly hot day, the makeup melted, and she was discovered and escorted off the bus. School authorities were less than pleased. She was disciplined, leading her to transfer to the more progressive University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

There, studying under the noted sociologist Frank Graham, she wrote a research paper analyzing the Southern cotton mill industry. Typically, she wanted to experience the working conditions firsthand. She got a job in a mill tending a spinning machine. Her paper graphically reported the long hours and low pay that were the pattern in the industry. The analysis reflected a talent for painstaking statistical research and a concern for social welfare issues. Both would blossom during her long career.

After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, Dorothy won a scholarship to study in Germany. She planned to research conditions in the German mines, but when she applied for a job, she was turned down.

“The unions said, ‘We don’t allow any women down in those mines. Those men don’t wear proper clothing, and we’re not going to have any ladies down there.’ So, I had to give up that project.”

Family roots and experience shaped her socially progressive point of view. Her mother, Sophia Lyon Fahs, was born in China, the daughter of evangelistic Presbyterian missionaries, and went on to become one of the acclaimed liberal reformers in religious education, profoundly influencing teaching in the Unitarian church. Dorothy’s younger sister, Lois, once commented, “Racial equality was a lifelong concern of all family members. We were raised that way.”

Dorothy was the oldest of five children. Family members found that her passion for collecting data was already evident at a young age. When she was 12, she embarked on her first social research project: assembling a small dictionary containing every word in her 2-year-old sister’s rapidly expanding vocabulary.

At the University of Chicago, while studying for a master’s degree in sociology, Dorothy met her future husband, Hubert Park Beck. Years later, Dorothy would tell friends of the courtship and marriage ceremony. They wrote their own vows for the ceremony on campus, and she practiced reciting them in the ladies’ room just before walking down the aisle.

As newlyweds during the Great Depression, they had little money. Park was teaching science in Bronxville, New York, earning $1,500 a year. The couple rented a railroad flat and ultimately moved their bed to one end, hung a curtain in the middle, and rented out a space to cover their expenses. During this period, they moved three times, and Dorothy began her career working for a number of private and government agencies, supervising research into the costs of medical and dental care and surveying the records of 10,000 families on welfare. One of her studies advocating free dental care for the poor created quite a stir in the profession.

Their only child, Brenda, was born while they lived in Minneapolis. In 1944, Dorothy received her doctorate from Columbia University. She and Park made their last move, to New York City, where she became a research statistician for the American Heart Association and then Cornell Medical College.

In November 1954, after a year abroad teaching at the American University of Beirut, the family of three took a sabbatical to retrace Marco Polo’s route through the Mideast and South Asia, visiting historical, educational, and cultural sites. They bought a second-hand bus and crammed it with provisions, old Army rations, cooking equipment, cameras, Dorothy’s painting supplies, and bedding—for they would sleep onboard during most of their trip.

The Americans frequently drew crowds of curious onlookers, and Dorothy and Brenda were the first unveiled women to venture into many of the Muslim villages on their journey. She later wrote several articles discussing the restrictions placed on women in Islamic cultures. She was troubled by these social traditions and tried to balance respect for the varied beliefs and ways of life she encountered with the belief that freedom and self-expression were the rights of women everywhere.

The trio subsequently wrote an account of the trip, titled “East of Beirut,” for a university publication. They returned home laden with mementos and artifacts. Years later, Dorothy’s nieces and nephews would visit her New York apartment and marvel at the tapestries and masks, the carved elephants, and the brass bowls. Her niece Nancy Timmins Kirk remembers these family gatherings with pleasure. “Visits to Aunt Dorothy and Uncle Park were like visits to another country.”

Dorothy resumed her professional career, which led to her most important and enduring assignment. In 1956, she became director of research for the Family Service Association of America (FSAA). She was the lead researcher for an organization that held under its umbrella 267 private social work agencies throughout North America. In this position, Dorothy had her greatest impact as an innovator, attempting to supply vision, purpose, and direction to those controlling the social welfare bureaucracy. “She was a pioneer,” said associate professor Mary Ann Jones of New York University’s School of Social Work, who worked with Dorothy at FSAA.

Professor Jones credits Dorothy with altering the way counseling and social services are evaluated in two important ways: insisting that the viewpoints of agency clients—and not simply those of professional counselors—be included in service evaluations; and opening an inquiry into counselors’ characteristics and the “fit” between them and clients as factors in determining the effectiveness of counseling and social services.

“She was concerned with anything that made an impact on the lives of individuals and families: marital enrichment, teenage pregnancy, domestic violence, race relations, child welfare, foster care. She gave clients a voice in their own service, an idea that is not unusual now—thanks in part to Dorothy’s work,” Jones said. When Dorothy retired after 25 years at FSAA, she was honored with an Outstanding Service Award from the Women’s Caucus of the association.

The Becks were active in the Unitarian movement and at the Community Church of New York. Dorothy always wished she could develop arguments and record evidence to help reconcile the disagreements that set “science” against “religion.” She felt the two disciplines should work together; that the discoveries and insights of each “naturally” lent support to the other.

Dorothy was in her 80s and a widow when she left Manhattan and moved to Crosslands, a retirement community in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. There, she produced programs for other residents, such as sharing her memories and insights of foreign lands, while she and her neighbors modeled the saris and robes Dorothy had brought back from her travels. She passed away on May 5, 2000 at the age of 94.

Among her many legacies is the Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation she created in 1993, enlarging on an earlier bequest co-founded with her husband in 1986. She wanted to support scientific and/or applied or policy research in five areas often handled by social workers, including counseling and family structures.

“These are not light subjects, but Dorothy had an abiding confidence that research in these fields could achieve results that would help people,” said Robert Edgar, former manager of the Fahs-Beck Fund under the aegis of The New York Community Trust. “I remember her talking to me in her 80s, vexed that many of the research topics her fund was being asked to support were not as much on the cutting edge as she would like,” Bob recalled. “She wanted to push the envelope, think outside the box, and challenge conviction.”