Record-setting Broadway actor helps those with visual disabilities.

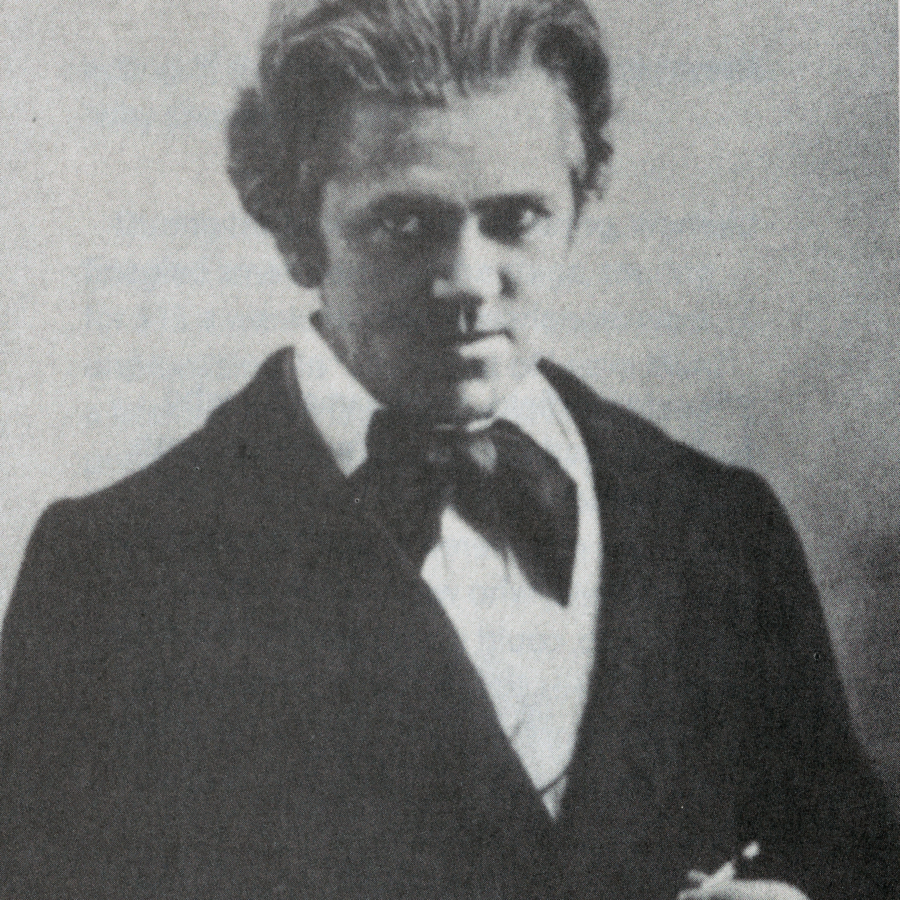

David Warfield (1866-1951)

David Warfield, a protean actor who shattered the record for the longest-running Broadway show in the early 20th century, was discovered at age 10 by a circus clown. Warfield, who was born in 1866 in San Francisco, could mimic almost before he could speak. His classmates in school were his earliest appreciative audience, but it was a trip to the circus that led to his first rave review.

His impromptu imitation of a clown reduced his subject to roaring laughter. He hoisted the boy on his shoulders, brought him into the ring, and announced, “Barnum will pay for this boy some day!” Warfield also loved Shakespeare. “Though I was a little humorist,” he later recalled, “the greatest tragedies moved me strangely.”

At 17, Warfield got his first job in the theater, handing out programs in San Francisco’s Standard Theatre. After three years, he became a $4-a-week usher in the Bush Theatre. For the next four years, he watched every great, near-great, and unknown American actor who came to town. “What made me determined more than anything else to become an actor was not the good acting that I saw, but the bad acting. ‘If that passes muster,’ I said to myself, ‘why shouldn’t I try?’ ”

During his four years of ushering, Warfield finagled small parts on the stage, touring for $15 a week. His first experiences were unpromising. In “The Ticket-of-Leave Man,” a false nose he had fashioned of glazier’s putty melted and dripped. After persuading the manager of the Wigwam, a 10-cent admission house, to let him perform imitations of well-known actors, he froze—distracted by the rattling of beer glasses and the commotion of late arrivals—unable to make any sound but a gurgle. He fled amid hisses.

But Warfield’s powers of mimicry soon made him the pet of the performers in local companies. David Belasco, the stage manager of the Baldwin Theatre, took particular note of his acting skill.

Despite early missteps, Warfield was more stage-struck than ever. At a benefit performance—for himself—he collected $100 from an audience of friends to pay for a trip to New York. His first public appearance was at Paine’s Concert Hall and Beer Garden on Eighth Avenue near 15th Street, where, in his $4 dress suit (his old usher uniform), he mimicked actors he had been unable to imitate at the Wigwam. The audience responded warmly, and he worked an entire week. Although he found Paine’s “an awful hole,” Warfield considered the experience a “turning point in my career.”

A chance encounter led to a role in a play about police life called “The Inspector,” and a weekly salary of $25. Then an appearance as an Irish scrubwoman in “O’Dowd’s Neighbors” caught the eye of John Russell of Russell’s Comedians. He signed Warfield to do his burlesque imitations, including takeoffs on Sarah Bernhardt and Tommaso Salvini, for a season with his City Director Company. And the following season saw the young comic as a farmhand in “A Nutmeg Match.”

Constantly expanding and improving his comic monologues, he played the vaudeville circuit, making stops at Keith’s and Tony Pastor’s in New York. At Pastor’s, manager George W. Lederer, who was known as a star maker, spotted him.

Featured as a comic and mimic at Lederer’s Casino, Warfield was determined to convince the manager there was humor potential in a Jewish character he had been developing. At a baseball game between the casts of “Merry World” and “Trilby,” he saw his chance. Expected to appear in the costume and makeup of his role in “Merry World,” Warfield appeared instead wearing baggy pants, a soup bowl hat scrunched down over his ears, and a shiny, disheveled frock coat. A fringe of uncombed whiskers masked his face. He ambled around the bases selling pieces of ice to a show business crowd that burst into applause. The next evening, closing night at the Casino, Lederer let Warfield perform his “Jewish Peddler” persona. It made David Warfield a headliner.

Featured as a comic and mimic at Lederer’s Casino, Warfield was determined to convince the manager there was humor potential in a Jewish character he had been developing. At a baseball game between the casts of “Merry World” and “Trilby,” he saw his chance. Expected to appear in the costume and makeup of his role in “Merry World,” Warfield appeared instead wearing baggy pants, a soup bowl hat scrunched down over his ears, and a shiny, disheveled frock coat. A fringe of uncombed whiskers masked his face. He ambled around the bases selling pieces of ice to a show business crowd that burst into applause. The next evening, closing night at the Casino, Lederer let Warfield perform his “Jewish Peddler” persona. It made David Warfield a headliner.

At that time, the vaudeville duo of Weber and Fields was at the top of the comic ladder. They invited Warfield to bring his Jewish Peddler to their “high-class burlesque.” The three years he spent with these burlesque masters, he later said, gave him “a splendid schooling in pure burlesque” that made dramatic roles “easy sailing.”

Warfield had been with Weber and Fields for a year and a half, honing his peddler character, when David Belasco sent for him. Belasco had moved from a stage manager in San Francisco to a leading producer of dramatic plays in New York. “I’ve had my eye on you for years,” said Belasco. “I want you for a star.”

It was the era when plays were written to fit the talents of specific actors, and Belasco outlined a role that combined humor and pathos—magic words to Warfield. As he recalled: “It was the most important change, in an artistic sense, of my whole life.”

Warfield’s contract with Weber and Fields had 18 months to run. He and Belasco shook hands in a gentlemen’s agreement. No further word came from the great producer—until a year-and-a-half later. Warfield read an announcement in the paper that producer David Belasco’s plans for the following season included “David Warfield in a new play!” That play was “The Auctioneer.”

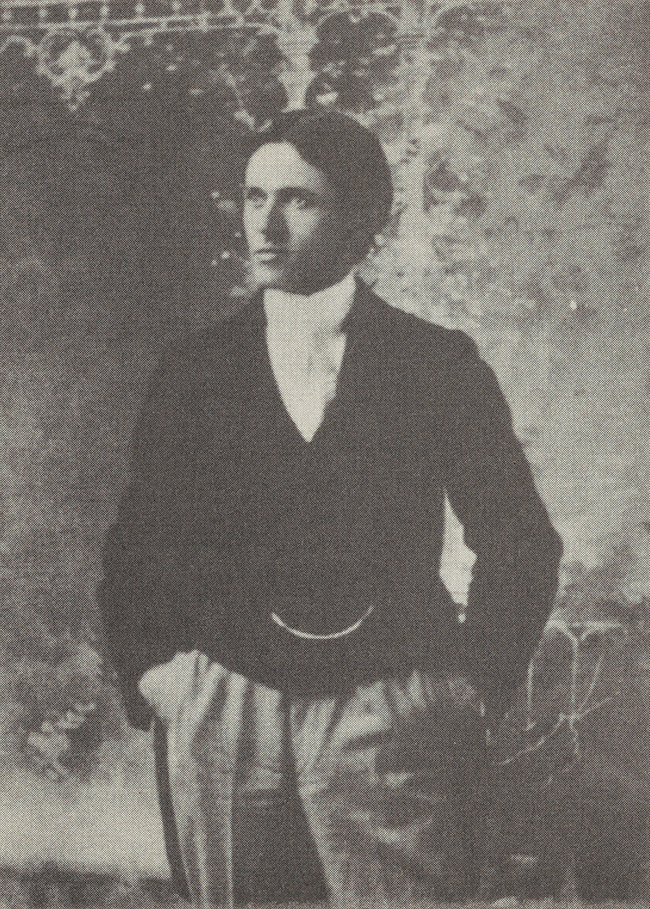

At age 35, after 11 years in New York, Warfield opened to wide acclaim as “the newest star on the theatrical horizon.”

The vague dramatic ambitions Warfield felt while clowning in vaudeville were now gathered in the character of a toy maker who becomes rich overnight, then loses his fortune two days later. Warfield thought the role’s aura of pathos required the ultimate form of characterization.

But the role was physically punishing. After nine months in New York and on the road, Warfield collapsed. The show was halted while the actor recuperated from exhaustion and appendicitis on a farm he bought in Ponkapoag, a village near Boston. When he recovered, Warfield moved into a 10th-floor apartment in the Hotel Ansonia on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, a favored residence of musicians and actors. Of his private life, little was known beyond the fact that on October 5, 1899, he married a New Jersey woman named Mary Gabrielle Bradt. As a celebrity, he was interviewed extensively and freely offered his opinions on his profession: “Hard work has nothing to do with success in the theater,” “actors cannot return to the varieties and then go higher up,” and “the player and the promoter must be faithful to each other.”

He denied rumors that he was entertaining offers from other managers. “I am with David Belasco for life,” he said. As if to prove it, Belasco’s new play, “The Music Master,” was announced. David Warfield would star in his first straight dramatic role as Herr Von Barwig, a music teacher who finds his long-lost daughter after a 15-year search but decides not to spoil her new life by claiming her. One reviewer wrote: “Mr. Warfield’s impersonation is one of the most natural and wholesome pieces of acting that one can imagine. He was the man from beginning to end. He took possession of his audience and held them as his very own until long after the curtain rang down.”

Warfield explained his oneness with the character of “The Music Master”: “On the stage, I have felt for a long time as if I were living a chapter out of the life of a great man. Von Barwig seems very real to me, and the longer I am this rare old music teacher, the more the psychological elements of the part absorb me.”

Audiences of the day recognized Warfield’s genius. As more raucous Broadway melodramas came and went, Warfield’s kindly music master moved serenely into its second and third seasons. “The play that the family talks about—that gets into the home—is the one that lasts,” Warfield said. “It is the human side that an actor must reach, and he can do that only by making a character human.”

It was a philosophy that paid dividends. With his tender parlor comedy, Warfield more than doubled the American record for longest-running Broadway show—a record set years earlier by tragedians Edwin Booth and Lawrence Barrett in a farewell engagement that offered their complete Shakespearean repertory.

Where did David Warfield’s ability to hold an audience come from? Perhaps his own words are revealing. Though he never “studied” acting, he had advice for the studious actor. “One thing the studious actor should not read is novels,” he said. “For, with a few notable exceptions, they give a false conception of human nature. Surely an actor, who mirrors life, must first find it. And he will not find it in the romancer’s fancy. He must know life from bitter, hard experience and observation. I disagree with Schopenhauer when he says the study and acquiring of life knowledge is difficult. It is not—unfortunately. It is heartbreaking, sometimes. It is slow, but not difficult. Indeed, it is too easy and too certain.”

Where did David Warfield’s ability to hold an audience come from? Perhaps his own words are revealing. Though he never “studied” acting, he had advice for the studious actor. “One thing the studious actor should not read is novels,” he said. “For, with a few notable exceptions, they give a false conception of human nature. Surely an actor, who mirrors life, must first find it. And he will not find it in the romancer’s fancy. He must know life from bitter, hard experience and observation. I disagree with Schopenhauer when he says the study and acquiring of life knowledge is difficult. It is not—unfortunately. It is heartbreaking, sometimes. It is slow, but not difficult. Indeed, it is too easy and too certain.”

Other plays followed: “The Grand Army Man,” “The Return of Peter Grim,” and “Van Der Decken,” which was Warfield’s only failure under Belasco’s management. But it was not until 1922, when he was 56, that Warfield realized his lifelong ambition to play that most human of character parts, Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.”

It was his farewell role. For his retirement, he offered a simple but profound reason. “I’d rather have people ask me, ‘Why did you stop acting?’ than ‘Why don’t you stop acting?’ ” he said. Two years later, he turned down an offer of a $1 million to perform “The Music Master” for a silent movie camera.

For 27 more years, Warfield lived quietly in his Central Park West apartment. If he missed the spotlight, he did not complain. He performed card tricks for a devoted circle of friends who played pinochle, and he collected expensive snuff boxes, renowned paintings, and art objects. Other than stock market quotations, Shakespeare was his favored reading. But reading and collecting became difficult, then impossible. When he died at 84 in 1951, David Warfield was blind.

In his will, Warfield set up a fund in The New York Community Trust. Today, the David Warfield Fund supports a variety of services, including those for people with visual disabilities.

“Surely an actor, who mirrors life, must first find it . . . He must know life from bitter, hard experience and observation.” – David Warfield