A textile entrepreneur with a passion for arbitration and archeology.

Charles Leopold Bernheimer (1864-1944)

Although he made his fortune in the textile business, Charles Leopold Bernheimer had two passions that could not have been more different: developing a single procedure to arbitrate industrial disputes and exploring cliff ruins and hunting for dinosaur bones in New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona.

In his 2013 book, “Outsourcing Justice,” Imre Szalai calls Charles Bernheimer the “Father of Commercial Arbitration.” Meanwhile, Charles dubbed himself the “tenderfoot cliff dweller from Manhattan,” and many of the relics collected on his expeditions are in the American Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian, and the Carnegie Institute.

Charles L. Bernheimer was born on July 18, 1864, in Ulm, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, to Leopold and Amalie Bing Bernheimer. His father was a dry goods merchant.

Charles graduated from Institution Thudichum in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1880, and immigrated to New York in 1881. The following year, he started as an office boy in the cloth-importing business owned by his uncle, Adolph Bernheimer. The company imported unfinished cotton and silk, dyed or bleached it, and sold the finished cloth to garment makers. In 1882 and 1883, Charles was joined by his brothers, Eugene and Adolph, and they continued the business as Bear Mill Manufacturing Co. By 1918, Charles was company president.

Charles married Clara I. Silberman, daughter of a New York silk manufacturer, on November 7, 1893, and they lived with their two daughters, Helen Amalie and Alice M., in a five-story walkup on East 64th Street.

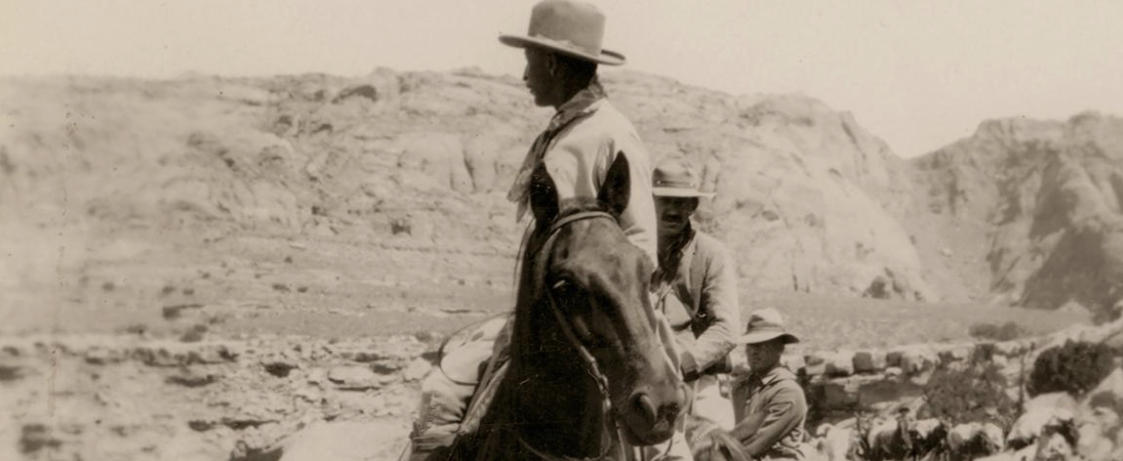

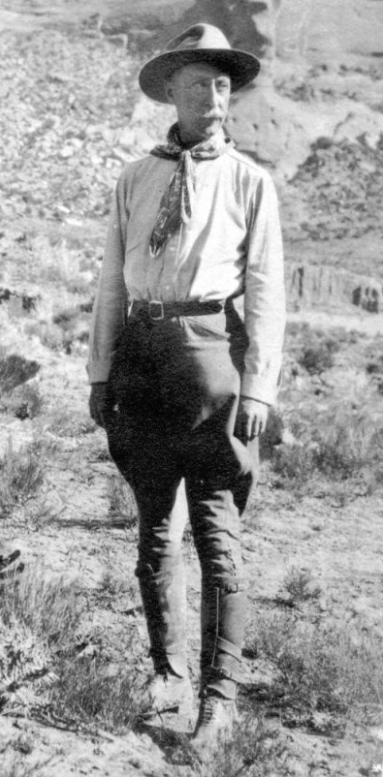

Every summer from 1919 to 1930, Charles left his family and the comforts of New York to explore the harsh desert and rugged mountains of the wild Southwest. Friends and colleagues wondered why.

“My answer is simple,” Charles wrote in his journal. “First of all, I love the desolate. I love to go where no white man has ventured before….The climate is dry and no tents or sleeping bags are needed. Any place having feed for the animals and water for all will do.”

Clara seemed to understand the desert’s pull on him. He recorded her encouragements in his journal: “Charlie, go and see the Rainbow Bridge as soon as possible. You won’t rest until you have done it.”

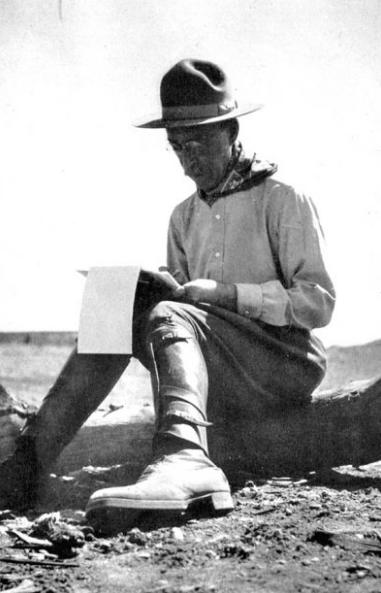

His destinations were archaeological and geological wonders: ancient Native American cliff dwellings, the Rainbow Natural Bridge, and uncharted canyon country. Not only did he keep detailed notes of his journeys, but his Kodak camera recorded everything from the “graceful, powerful and perfectly symmetrical” Rainbow Bridge, as he described it, to the simplest details of camp life. Though he tried to dress in the same heavy leather and high leggings as his guides, John Wetherill and Zeke Johnson, aristocratic Eastern ways die hard. In his journal from the 1919 expedition, Charles mentions one of the pack horses carried his “dress suit case.”

Subsequent excursions into the Four Corners region—Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico—were more significant. In his journal, Charles wrote: “A large number of unnamed places, canyons and mesas received appropriate names which we hope may become permanent.” His Southwest campaigns also discovered more natural bridges, remnants of cliff dwellings and dinosaur tracks, which the American Museum of Natural History described as among “the most perfect specimens ever discovered.”

When he wasn’t exploring the badlands of the Southwest in summer, Charles was hard at work in New York—and not just at Bear Mill, the family’s cloth-finishing business.

As chairman of the Committee on Arbitration of the New York Chamber of Commerce, Charles was an arbiter for labor disputes.

In his book “Outsourcing Justice,” Imre Szalai wrote that Charles Bernheimer made it his life’s passion to promote arbitration as an alternative to burdensome litigation. “He appears to have pushed for reform out of altruistic motives rather than for any selfish or evil motives to strip away rights from unknowing individuals,” Szalai wrote.

Szalai credits Charles’ extensive lobbying efforts for the passage of New York’s arbitration statute in 1920, and the Federal Arbitration Act of 1925. As a result of this law, courts do not have the authority to set aside arbitration awards if the arbitration agreement is valid.

Clara died on October 12, 1932. As a tribute to her, Charles named a 140-foot arch within Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park the Clara Bernheimer Natural Bridge. The span is in a remote canyon near Hunts Mesa, Arizona.

Charles died on July 1, 1944, in Manhattan at age 79.

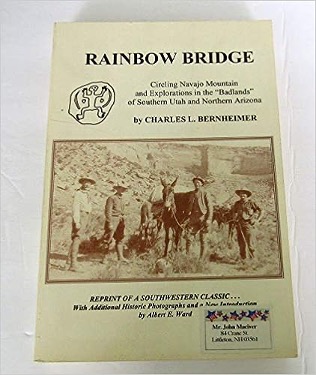

His book “Rainbow Bridge: Circling Navajo Mountain and Explorations in the ‘Bad Lands’ of Southern Utah and Northern Arizona,” first published in 1924, was reissued in 1999. It focuses on his 1921, 1922, and 1923 excursions.

The fund Charles Bernheimer established in The Trust has made grants to nonprofits providing civil legal, immigration, conflict mediation, and other services.