He was editorial page editor of The New York Times during tumultuous ’50s and ’60s. She was a member of The Trust’s Distribution Committee.

Charles Andrew Merz (1893-1977)

Evelyn Scott Merz (1896-1980)

It was a rainy summer day in 1923 when Charles Merz met Evelyn Scott. He was on the local Sandusky, Ohio, golf course. “I got off a magnificent drive, which sliced, as my drives often did, onto the approaching fairway.

“Coming up the fairway was the future Mrs. Merz. If I hadn’t been there in Sandusky, and if I hadn’t sliced the ball, I would never have met her.”

Evelyn was born in Hyde Park, Massachusetts, on August 27, 1896. At Simmons, she majored in science and, after graduation, taught school in Maine before moving to Bennington, Vermont. There she wed Charles Merz in 1924.

The lifetime they began together intertwined with some of the outstanding events and personalities of the mid-20th century. Evelyn became a member of the Distribution Committee of The New York Community Trust and a trustee of the China Institute in America; Charles had a spectacular newspaper career.

“Work Hard and Keep Trying”

When asked about his background as a newspaperman, Charles Merz said, “As a boy, I wanted to go into newspaper work and edit a small newspaper of my own. In journalism, as in most other things, it seems to me that the best thing to do is to work hard and keep trying.” It was advice taken to heart by the man who for 23 years at The New York Times presided over the nation’s most influential editorial page.

The Merz urge to write predated Charles by at least two generations. Charles Merz’s paternal grandfather, Karl Merz, was a musician who, after emigrating from Germany in 1854, settled in Sandusky, Ohio, a town 60 miles west of Cleveland on Lake Erie. There he edited the publication Musical World and headed the music department at Wooster College. He was commemorated at the college by Merz Hall, which has since been renamed Gault Alumni Center.

Karl Merz’s son, Charles Hope Merz, became a doctor. Never a bookkeeper, he jotted patients’ names or descriptions on scraps of paper, such as “lady with red hat, four visits.” He never sent bills, and the only money he earned was from patients who would come in and ask what they owed. He always said $20.

When not contributing his medical skills to Sandusky—which he would do until the age of 86, Dr. Merz edited and wrote extensively for a Masonic bulletin. During his lifetime, he published four books on Masonry.

Dr. Merz married Sakie Emeline Prout, whose ancestors came from Easton, Connecticut. Charles Andrew Merz, born February 23, 1893, was their only child.

Family lore has it that young Charles first set pen to paper at age 6, writing in a burst of enthusiasm for his musician grandfather:

“I love Grandpa so much that I don’t know how much I love him. Horses are useful for hauling wagons and another reason is to haul a load of corn to make the chickens fat and another reason is to give the pigs some. Eat quaker oats and it will make you strong and fat.” Soon afterward, he was editing his own newspaper, his sources presumably the visitors who left calling cards in his mother’s silver dish. In later summers, he wrote local stories for the Sandusky Register.

Charles also used his reporting ability with baseball, rooting for the nearby Cleveland Indians and memorizing baseball statistics like many other young Americans. His uncle, George West, was a friend of Byron Bancroft (“Ban”) Johnson, president of the American League. In 1904, West arranged for the Boston Red Sox to stop in Sandusky for a Sunday game. Watching the game outside first base with his uncle and Ban Johnson, 11-year-old Charles so impressed Johnson with his knowledge of baseball that for the next 14 years the official sent the young man an annual pass, good for any American League game.

The year 1911 brought two events of note: Charles graduated from Sandusky High School and his father inherited $4,000. After checking with his son to see if this would cover four years of college, Dr. Merz gave him the whole sum. With that, Charles was on his way to Yale.

Moving East

Remembering the experience for The New York Times many years later, he said: “Nobody in my town had ventured to go to an Eastern college…. I had never been outside of Ohio until I took the train to go to New York and then New Haven, except once, when I was taken as a small boy to Buffalo to the Pan American Exposition…. To come East from high school and meet all these lads who had, most of them, come from large preparatory schools was a very refreshing and interesting experience.”

The “History of the Class of 1915” calls him “Doc,” and notes that he “expects to take up literature and has written during college in preparation for his career.” He majored in English, and his classmates included poet and playwright Archibald MacLeish and Dean Acheson, statesman and lawyer. In 1914, Charles Merz coauthored the spring play and acted the part of the Tired Business Man in another play, “Behind the Beyond.” He was press manager of the Dramatic Association, editor of the Yale Record, member of the Elizabethan Club, Wolf’s Head Society and Zeta Psi, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

Graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1915, Charles went to work for Harper’s Weekly that fall. The publication was doing badly, and many people, foreseeing its demise, were leaving. By November, he was managing editor. Even though it was a short-lived assignment (the magazine closed the following spring), it was long enough for Walter Lippmann, who met Charles at some magazine editors’ meetings, to take notice of the fact that he was a managing editor at age 23.

Freelancing after the demise of Harper’s Weekly, Charles filed a story for Everybody’s Magazine from the Mexican border on the difficulties of mobilizing troops to chase the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. A copy of the article, torn from the magazine, was sent back to him with the note: “This is bully stuff. T.R.” And under that: “Come and lunch, I will have my secretary call you.” A month later, Charles lunched with Teddy Roosevelt at Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay.

Merz saw T.R. another five or six times in his life. He recalled that on one occasion the president said, “How do you think the war’s going?” “He had me down as a military expert,” Charles said. “He never forgot me. And every time I saw him, it was always some military question.”

In 1916 Charles joined The New Republic, serving as its Washington correspondent until the U.S. entered World War I. He was commissioned a first lieutenant in military intelligence and went to France in 1918. In 1919, he was named an assistant to the American commission at the Versailles Peace Conference.

Into Newspaper Work

After the war, Charles rejoined The New Republic and began working with Walter Lippmann. In August 1920, they published “A Test of the News,” their survey of press coverage of the Russian Revolution from 1917 to 1919. The report was critical of New York Times reporting, citing it as neither complete nor accurate. The coverage, Merz and Lippmann concluded, reflected the hopes of the paper’s editors for the failure of the Soviet regime rather than the reality of its strengths.

Editor and Publisher said the survey brought “epochal results. The Times acted vigorously” to change its reporting system and, in so doing, “led a nationwide improvement in international reporting.”

The same year, Charles set out on an extended trip through the Middle East, to Egypt, India, Malaysia, China, Korea, and Japan. Back in the States in 1921, he became a staff correspondent for the New York World and, as a first assignment, covered the Washington Disarmament Conference. In 1924, he became associate editor of the editorial page. This also was the year he married Evelyn Scott.

After their wedding, Charles and Evelyn moved into their first apartment in New York, near Washington Mews, in Greenwich Village. Walter Lippmann found it for them. Five years later, they moved into a spacious co-op at 10 Gracie Square, overlooking the East River, where they lived the rest of their lives. When the New York World folded in May 1931, Charles Merz joined The New York Times as an editorial page writer. He was interviewed by Arthur Hays Sulzberger, who wrote to Adolph Ochs, the publisher: “Merz is a devoted admirer of The Times, and in every way impresses me as the type of man it could be well to bring into the organization.”

A Special Friendship

A warm friendship developed between Merz and Sulzberger that lasted the rest of their years. “As it blossomed, we got to know each other better and to like each other more all the time,” Merz said. Away from The Times, Charles and Evelyn and Arthur and Iphigene Sulzberger spent a great deal of time together—weekends at “Hillandale,” the Sulzberger home in White Plains, and on vacations.

To the Sulzberger children—Marian Heiskell, Ruth Holberg, Judith Sulzberger and Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger—they were “Uncle Charlie and Even,” and they were adored. To the Merzes, the younger Sulzbergers were the children they did not have.

“Everybody loved Even. Oh, she was absolutely enchanting,” recalled Marian. Seconded Judith: “She was a very beautiful, very accomplished person. Full of charm. Whenever she walked into a room, men would just gather around her. What can I tell you? I adopted her as my godmother.”

Memories of Charles were equally glowing. Ruth said: “We always looked on him as a kind of parent. He was an extremely warm human being. It quite belied his appearance. He was very tall, and he stood very straight. I guess if you first saw him, you’d think of ‘Prussian.’” Added Judith: “She was much more lively, and he adored her.”

Weekends at Hillandale were fun. Evelyn, who had studied piano at the Von Ende School of Music in New York, would gather the children for songfests around the Sulzbergers’ piano. There would be swimming, and friends dropping by, and always some kind of puzzle set out for everyone to work on. Usually, they were huge, intricately cut jigsaw puzzles, with 2,000 or 3,000 pieces.

Arthur recalled those in a poem:

With eyelids heavy and drawn,

With fingers weary and raw

An editor sat in his bathing trunks

Doing a damned jigsaw.

Piece, piece, piece.

Though company come and go,

The editor sat in his nudity

Placing each piece just so.

Merz and Sulzberger, at leisure, were crossword puzzle aficionados, enjoying both the basic form and the more complicated acrostics. They even authored their own, one giant version of which appeared in the Sunday New York Times Magazine in June 1942, signed by both of them. In 1954, Simon and Schuster included another of their masterpieces, Double-Crostic Number 53, in the 20th anniversary edition of “Kingsley’s Double-Crostics.”

Charles Merz wrote several books in the ’20s and early ’30s: the 1924 “Centerville, U.S.A.,” a portrait of an American small town and its people, inspired by his own upbringing in Sandusky; “The Great American Bandwagon,” a collection of essays on Americana, in 1928; “The Dry Decade,” a history of Prohibition, in 1931; and, with Lippmann, “The United States in World Affairs in 1932,” in 1933.

One of his most famous editorials appeared on June 15, 1938. Sulzberger, on a trip abroad, had talked with various European chiefs about their fears and concerns regarding Germany and Japan. Upon his return, he discussed his findings with his editorial staff. The consensus was that it was time to tell Americans where they stood in the gathering storm, and that there was no way they could isolate themselves from it when it broke. The result was “A Way of Life,” drafted, as was Charles’ custom, in soft lead pencil on a yellow legal pad. It said in part:

“Though the United States has lived for two years under a Neutrality Act which expresses its wish to remain at peace, the American people are not neutral now in any situation which involves the risk of war, nor will they remain neutral in any future situation which threatens to disturb the balance of world power.

“… The truth is that no act of Congress can conscript the underlying loyalties of the American people … Statesmen abroad who fail to reckon with this fact because they are impressed by … the Neutrality Act …, or because they think that the United States lies at too great a distance from the scenes of potential conflict … enormously miscalculate a well-established American habit of choosing sides the moment an issue basic to this country’s faith is actually involved.”

“A Way of Life” and other pre-Pearl Harbor editorials were later published in Merz’s “Days of Decision.”

Editorial Page Editor

In November 1938, Charles Merz succeeded John H. Finley as editorial page editor of The Times. Sulzberger had offered him the job during a Hillandale weekend. “I remember the day it happened,” recalled Merz, “because it was a very pleasant feeling to be asked to do it…. We were sitting in the room that still holds the memory of the million-piece picture puzzles, and the Chinese checkers games, and the gin rummy games, and the backgammon games, all of which Mr. Sulzberger and I slugged each other out at. He came in just before lunch and said: ‘I’ve been thinking things over. Dr. Finley is not in good health and certainly isn’t in a position to go on—he’s only been editor in title. How would you like the job?’ ‘I’d like it,’ I said. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘that’s a bargain.’ We shook hands, and I said, ‘Can I tell Mrs. Merz? She’s upstairs playing some game with Punch.’” Evelyn, with a solemnity suited to the impressive news, assured Sulzberger that “Charles will never fail you.”

The change, of course, was duly noted in the newspaper world. The Norfolk Virginian-Pilot had this to say about Merz: “He brings a fresher outlook and a stronger liberal inheritance from his younger days, and suggests something of the new spirit which has come in since Arthur Hays Sulzberger, another young man, became publisher. Whether he can or will alter the character of an editorial page that is slow to change and sometimes seems bowed by the weight of centuries cannot be known now; but at least he assures that passion for exactness and that deliberate judgment which makes the opinions of The Times a powerful and civilizing influence.”

Sulzberger and his editorial page editor saw eye to eye, agreeing upon what kind of an editorial page they wanted The Times to carry. “Unless there was some new change, some departure from the stands we’d been taking, I never consulted him at all,” said Charles. “He had confidence that I would not try to swerve the paper into a new channel without letting him debate it with me, and if he disapproved, have it out with me. But for the rest he trusted my judgment, I think, because this system worked very well.”

Charles made a practice of asking others on the newspaper, besides his own staff, to contribute editorials from time to time—Brooks Atkinson on theater, sportswriters on baseball. In one year, he recalled that at least 50 people wrote editorials, which was not at all irregular.

Sulzberger never used his lead pencil on any of them. He did write editorials himself, however, although none ever was published. “He would be furious about something that had happened in the news,” Charles said, “and send down an editorial. ‘Dear Charlie, I hope this gets in tomorrow.’ Usually it was short, and very, very abrupt.

“Later in the day, he’d call and say, ‘Are you using that editorial?’ And I’d say, ‘Arthur, I’m not using it.’ Then he’d say, ‘Well, damned glad you’re not. I lost my temper about that. I was going to ask you not to use it.’ I had a collection of them at one time.”

Beginning in 1937, Charles became a regular member of the newspaper’s weekly luncheon group, made up of a few editors and the publisher who, each week, invited a national or international figure to be their guest. The invitees included Eleanor Roosevelt, Charles Lindbergh, Lyndon Johnson, John Masefield, Soviet diplomats, Thomas Dewey, Nelson Rockefeller, Joseph Kennedy, Jack Kennedy, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Winston Churchill, David Ben-Gurion, Casey Stengel, Adlai Stevenson, Robert Wagner, Arthur Rubinstein, and many others.

When Churchill was the guest, it was in the middle of winter and there was a fire going in the fireplace. Merz remembered standing next to him in front of the mantel when the waiter came around with glasses of sherry. Churchill turned to him and said, “My god, this isn’t all we’re going to have to drink, is it?” Charles assured him that it was not, and that Champagne would follow.

“He would sweep anybody off his feet,” said Merz. “He dominated the dinner.”

Access to such world leaders, whether in the United States or abroad on field trips, was for Charles an understood part of the job. “You would have no great difficulty, if you were polite enough, in getting to see different presidents and prime ministers,” he explained. Konrad Adenauer came to mind, and Clement Attlee, as well as Churchill and Anthony Eden. “I would see them on these trips and gather their impressions of what was happening.”

“The Voice of a Free Press”

The Senate hearings conducted by Joseph McCarthy in the early 1950s were followed by an event of even greater import to The New York Times. This was the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee investigation, headed by Sen. James O. Eastland of Mississippi, in 1955 and early 1956. While the stated concern of the Eastland Committee was to investigate communism in the press, it was clear by the end of the first day’s hearings that The Times was the target of the committee’s attack. In reply, “The Voice of a Free Press,” penned by Merz, ran on January 5, 1956. It made the point that:

“It is our own business to decide whom we shall employ and not employ. We do not propose to hand over that function to the Eastland subcommittee.

“Nor do we propose to permit the Eastland subcommittee, or any other agency outside this office, to determine in any way the policies of this newspaper….

“We cannot speak unequivocally for the long future. But we can have faith. And our faith is strong that long after Senator Eastland and his present subcommittee are forgotten, long after segregation has lost its final battle in the South, long after all that was known as McCarthyism is a dim, unwelcome memory, long after the last Congressional committee has learned that it cannot tamper successfully with a free press, The New York Times will still be speaking for the men who make it, and only for the men who make it, and speaking without fear or favor, the truth as it sees it.”

To Charles Merz that editorial was the most important piece of prose he had ever written, and the most important declaration of The Times during his tenure and that of Arthur Sulzberger. Reprinted in every significant newspaper in the United States and abroad, its powerful effect echoed around the world.

At The Times, applause rang out. A note from Drama Critic Brooks Atkinson said: “As in all pieces of brilliant prose, the writing is not to be separated from the ideas. In this instance, the prose reminds me of Shaw’s prefaces: Shaw could use simple, homely words with a passion that made them look like flames.” City editor Frank S. Adams said: “For 31 years I have been proud of being a member of the staff of The New York Times, but never quite so proud as I am today. This was The Times at its best: dignified, proud, honest, and fearless.” And from Howard Taubman in the music department: “May I say well and bravely done on this morning’s lead editorial.”

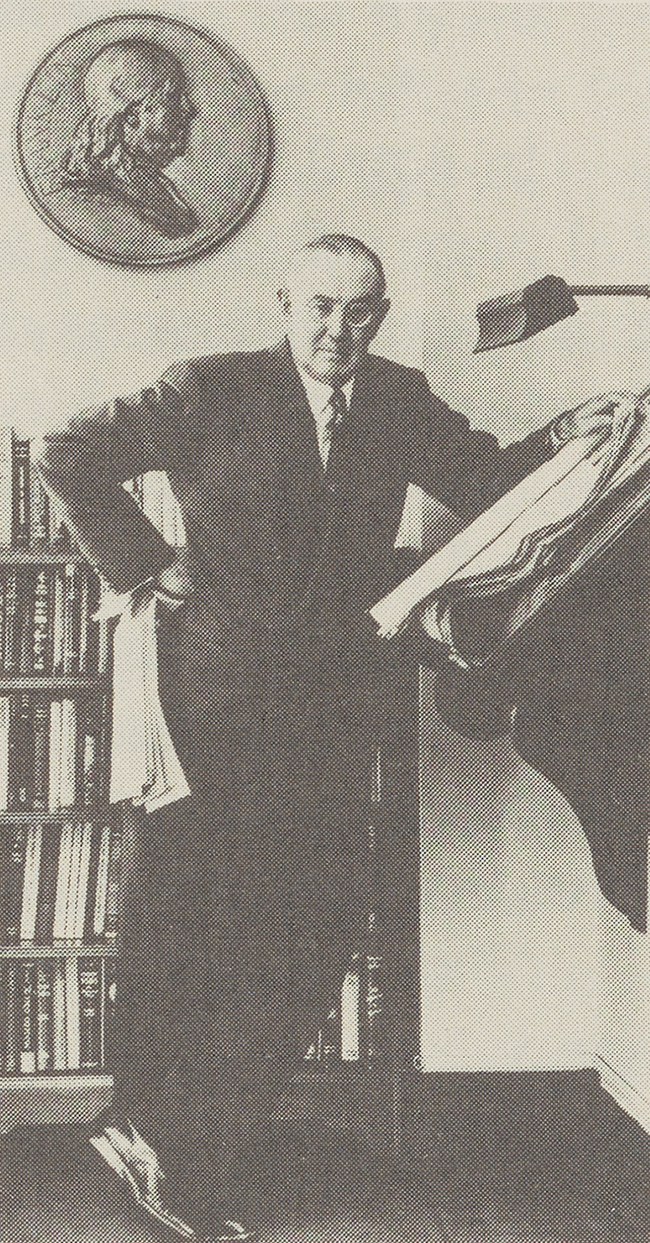

Editor Emeritus

In April 1961, Charles Merz retired as editorial page editor and accepted the title of editor emeritus. That same day, Arthur Sulzberger retired as publisher. He sent a note:

“Dear Charlie: ‘Misery likes company’ and while I know that you and I are pursuing the right course, I also know that there’s a lot of heartache associated with it. As someone said to me the other day, ‘This is the first milestone you have ever passed that hasn’t pointed up.’

“But we are putting The Times in capable hands and the problems that you and I had when you first took over the page are not present. So cheerio and God bless and I’ll be seeing you.”

Charles and Evelyn began dividing their time between New York and Cape Cod, first in a house in Hatchville and later, one in Sippewissett, near Falmouth, on Buzzard’s Bay. Occasionally, when his successor, John Oakes, asked him, Merz wrote an editorial for The Times, but after a few years he stopped altogether. When in New York, he came to the office four days a week. He also served as a trustee of the Guggenheim and Russell Sage Foundations.

Evelyn had long been a member of the Cosmopolitan Club in New York’s East 60s. Among the top clubs for women, the Cosmopolitan was known to choose members for their accomplishments and not for social stature alone. Certainly, a distinguished aspect of Evelyn’s accomplishments was her service, from 1959 to 1968, on the Distribution Committee of The New York Community Trust. A favorite of then-director Ralph Hayes, Evelyn was asked by Hayes to represent the Distribution Committee on the board of the James Foundation, which shares staff with The Trust.

Charles and Evelyn stayed in the city only during the winter months. “By the time April comes,” said Charles, “I’m so bored with the noise, the dirt and confusion, and the traffic and the taxi fares of the city, that I can hardly wait to get off to the Cape. And vice versa, when the nights get long and there isn’t a light on the hillside for miles around—you can almost hear the wolves barking—I think of the city again.”

So, they divided their time until failing health and the infirmities of age forced them to stay close to their New York home. Charles Merz died there on August 31, 1977, at age 84; Evelyn Scott Merz, on April 29, 1980, at age 83. They are buried, as they both wished, on Cape Cod.

“They complemented each other,” said Judith Sulzberger. “They were a great couple.”

In a tribute written for The Century Association after Charles Merz’s death, John Oakes said: “Although a writer of great power, clarity, and eloquence, he characteristically shunned publicity, preferring the anonymity of the editorial page to the glamor of the byline. His views, usually expressed with great moderation, were shaped by his basically liberal philosophy, a deep-seated devotion to American democracy, a concern for human rights and civil liberties and a profound hatred of every form of totalitarianism whether of the Left or of the Right.”

“I am an American,” wrote Charles Merz in 1942. “It is a friendly way of life, with room for the opinions of the man across the street…. It is an alert way of life, on guard day and night against impairment of the rights that a free people cherish: the right to think for themselves and to vote as they please, to choose their own church, to read a free press, to name their own leaders in a free election; the right to discuss, to disagree, to try new roads, to make mistakes and to correct them; the right to be secure against the exercise of arbitrary power.”

Charles and Evelyn Merz invested their lives in preserving basic American rights. Their commitment continues today: Charles and Evelyn Merz specified in their wills that the remainder of their estates, after final expenses, be used by The New York Community Trust to enhance the quality of life in perpetuity for the generations of New Yorkers who would come after them.