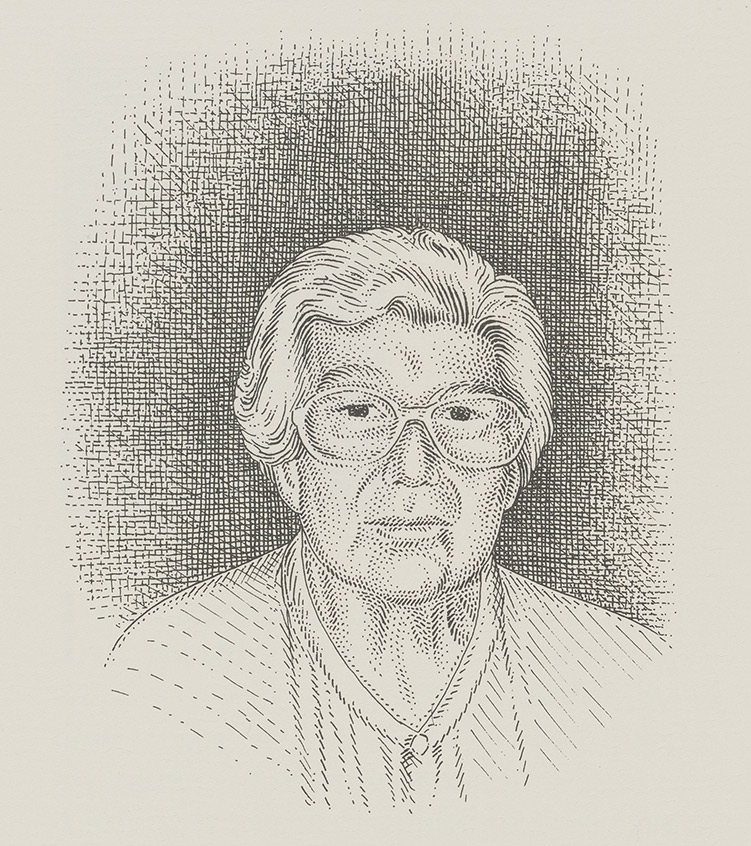

A woman devoted to biological research whose fund at The Trust supports public health research.

Carolyn Rosenstein Falk (1902-1994)

In an age when the privileged daughters of wealthy New York families often were content to enjoy youthful good times capped by an early and proper marriage, Carolyn Rosenstein took a different path. Unlike her two younger sisters, she chose to pursue a career in science, making her way in the challenging field of bacteriological research. Parties did not interest her; laboratory work did. Family members were puzzled at first by her choice, but Carolyn was always strong-willed and independent.

“We all knew she had a brilliant mind,” said her sister-in-law, Helene Linenthal, one of the few family members who remained on relatively intimate terms with Carolyn over the decades. “Ours was ‘The Great Gatsby’ crowd, but Carolyn, by choice, stayed outside.”

The Rosensteins owned an estate overlooking the Hudson River near Tarrytown, and all three daughters were schooled privately at Miss Mason’s, a private girls’ school in Tarrytown, but Carolyn alone went on to Smith College. While at college, she joined a group of undergraduates who regularly attended religious services at St. John’s Episcopal Church on campus. Although the Rosensteins were Jewish, Carolyn was drawn to the Anglo-Catholic teachings and formally converted. From then on, science and devotion to her newly adopted religion became major forces in her life.

After graduation in 1923, she returned home and secured a beginner’s position in a laboratory. These were difficult times for a newcomer, and particularly a woman. Initially, she worked as a volunteer at the Department of Health, either driving herself to work in Manhattan or staying at the family’s Manhattan apartment. After the customary four months’ probation, she passed the Civil Service exam and was hired as a laboratory assistant in bacteriology. Two years later, she passed the bacteriology exam but had to wait another four years for an appointment.

Carolyn was enthusiastic about her work, which was reflected in letters to Smith College: “The work is getting increasingly interesting,” she wrote. “The Typhoid epidemic of 1925 was our first big thrill, and we’ve had several lesser ones in the ‘Parrot Fever’ epidemic in 1929 and the more recent ‘Infantile Paralysis’ one.”

Promotions were coming her way. The department put her in charge of sterility testing on all biological products it distributed. She also published medical papers, and several of her articles appeared in the American Journal of Public Health and in the Journal of Experimental Medicine from 1926 to 1932.

The laboratory work with toxins and antibiotics had its moments of crises: On one occasion, she accidentally swallowed a substance with potentially lethal effect. Quickly, she reached for an antidote—she gulped a full tumbler of pure alcohol. Later, she enjoyed retelling the story of her experience, often adding that it provided lasting immunity to ill effects from any amount of alcohol—insisting it allowed her, without worry, to indulge in her favorite cocktail, a whiskey sour.

At the Department of Health, she met a fellow researcher, Dr. K. George Falk, a biochemist who had graduated from Columbia University and the University of Strasbourg in France. He also was a professor of chemical bacteriology in preventive medicine at New York University’s School of Medicine. She was 33. Dr. Falk, a widower, was in his 50s. The two were married on Oct. 16, 1935. A rabbi and an Episcopal minister officiated at their wedding.

The couple had no children. Their shared interest in scientific research apparently made it a companionable union. During summer vacations, they traveled; they spent their holidays on Nantucket. Carolyn had infrequent contact with her family except for Helene Linenthal, who had been married to her only brother, Louis Rosenstein Jr. He was killed during World War II. Helene has recollections of the Falks enjoying their summers, sitting on the veranda of Nantucket’s White Elephant Inn in their rockers, often buried in medical papers and seemingly not needing to communicate with others.

On their outings, Dr. Falk was satisfied to leave the driving to his wife, and she was only too happy to oblige. She would continue to drive until she was incapacitated by age and illness. She received her last license renewal when she was 90, apparently without difficulty because her record was unblemished—never an accident.

Carolyn apparently had no misgivings about being the “second” wife. When she moved into Dr. Falk’s richly decorated apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, she left a large oil painting of his late wife, Dora, prominently displayed.

After her husband’s death in 1953, Carolyn seemed less eager to pursue her medical career. She spent more time at her summer home in Brewster on Cape Cod overlooking the water, always accompanied by her beloved Yorkshire terriers.

Increasingly, she devoted herself to the church, both as a member of Church Women United, the Council of Churches, and her parish in New York, the Church of the Resurrection.

Father Allan Warren recalls her enthusiastic and generous support of the church’s charities. She directed a number of its fundraising activities, hosting a High Tea every year at her home, where she always provided church benefactors with a jar of her homemade preserves. And Thomas Rae, the church’s long-time treasurer, has a vivid image: “At Easter, she always wore a black straw hat with flowers—she only wore it to church once a year.” This was as close to vanity as she cared to come. She was reluctant to be photographed, rarely spoke about herself, and was never seen wearing the jewelry she inherited.

Carolyn also became a devoted supporter of the Sisters of Mary Convent in Peekskill, New York, and of the work of St. Mary’s-In-the-Field, an Episcopal order that helped care for abandoned, neglected or delinquent children.

In her later years, when movement was restricted and she had to use a cane, she developed a passion for entering contests—a way to use her still active intellect. She subscribed to scores of publications to pursue her hobby. She also discovered television game shows and soap operas. But whatever she watched or read, she ended the day reading her Bible.

Carolyn died in 1994, at age 92. Her will made small bequests to relatives, her caregivers and to provide for her pets. There also were provisions for both Smith College and the Church of the Resurrection in New York, and for her favorite charities. But the bulk of her fortune was left to The New York Community Trust for chemistry and biochemistry research relating to the public health and involving a definite problem or piece of scientific work.

“She always was hoping for cures for disease. That’s what she wanted,” said Helene Linenthal. Carolyn’s fund at The New York Community Trust memorializes her parents, Pearl and Louis Rosenstein; her husband, and Dora, his first wife; and cousins of Dr. Falk, Morris and Louise Lichten.