A giant in retail whose patronage of visual art extended to New York City.

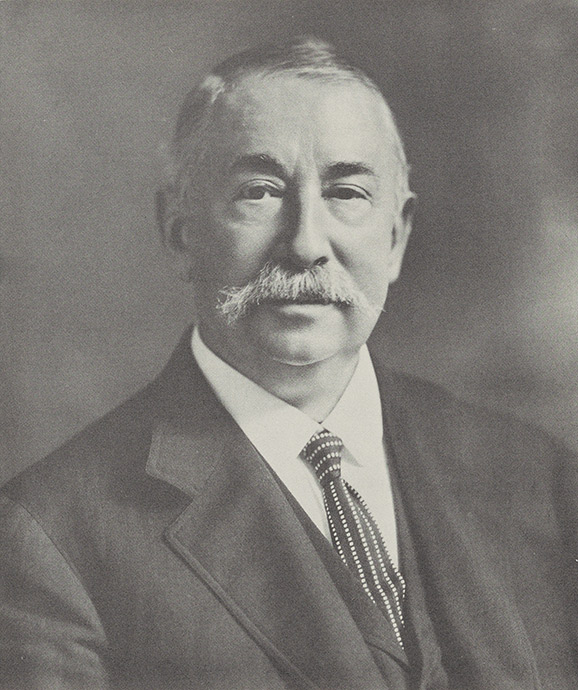

Benjamin Altman (1840-1913)

He built one of the great retail stores in America, then gave it all to a charitable foundation to benefit other people. He also built one of the country’s great art collections, then gave it away so others could enjoy it.

Benjamin Altman was born in New York City on July 12, 1840, the second of three children. His parents, Philip and Celia, were Jewish immigrants from Bavaria who came to America around 1835 and settled on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in a flat on Attorney Street, where Benjamin was born.

His father had established a modest dry goods store that provided Benjamin with his earliest experiences in shopkeeping and trade. After a day’s lessons at a nearby public school, Benjamin’s attention turned to tending the counter, serving the customers, and doing whatever chores needed to be done in the family store. He found this kind of work fascinating. By the time he was 12, Benjamin’s formal education had come to an end. In a pattern familiar to youth of that time, the boy withdrew from school to work full time in the family enterprise; he was no longer a child.

Benjamin also worked briefly in a number of stores outside New York—a general store in Clarksville, Virginia, and one or two dry goods stores in Newark, New Jersey. At one of them, Benjamin met two other young men who, like himself, would later establish large department stores—Abraham Abraham of Abraham & Straus, and Lyman G. Bloomingdale of Bloomingdale Brothers Inc.

A Store of His Own

When Benjamin was 23, his father died. Two years later, in April 1865, Benjamin leased a store of his own for $40 a month at 39 Third Ave., between Ninth and 10th Streets. It was a small shop with no more than 2,500 square feet of floor space, but the 25-year-old Benjamin was able to make it prosper. Within five years, he was ready to move the business out of the Bowery and take it to what was then becoming New York’s central shopping district, the neighborhood of Broadway and Sixth Avenue between 18th and 23rd Streets. Major established stores, such as Arnold Constable and Lord & Taylor, were taking their businesses to Broadway, and Benjamin’s older brother, also an ambitious entrepreneur, already was part of the trend. In 1876, Morris Altman built a new “Palace of Trade” on leased property at the northwest corner of 19th Street, where he intended to house a high-volume retail store and more than 200 employees.

Suddenly, in mid-July, Morris died at age 39, followed soon after by his wife. Benjamin was stunned; he was left to care for their orphaned children and manage the new department store. Over the years, Benjamin raised and educated his two nieces and two nephews, one of whom, Fred, later worked in the store.

Altman & Co. Is Born

Benjamin changed the name of the store to simply B. Altman & Co. In April 1877, the building at 19th Street and Broadway was an elegant, six-story structure designed in the Neo-Grec style, with an interior dominated by a splendid court that extended the full height of the building to a glass and iron dome.

Benjamin decided the architectural beauty of the store should be matched with an exquisite selection of goods. Instead of selling medium-price merchandise, as many competitors did, Benjamin stocked only the finest silks, satins, linens, laces, and velvets; the most stylish ladies‘ fashions; the most luxurious rugs; and exceptionally beautiful ceramics, sculptures, and other objects of art. Benjamin made sure the city’s most affluent customers were attracted to Altman’s, and his customers delighted in the pleasures of his store. They came to respect the Altman label as a hallmark of quality.

The store’s success proved Benjamin’s genius for business. When he opened it, the country was emerging from a depression and moving into a long period of prosperity; prices declined, and a bewildering array of manufactured goods attracted consumer spending. The customer base broadened, population increased, and urbanization advanced. These were extremely important factors for the retail trade, and Benjamin responded astutely to them. He plowed his profits back into the store and expanded. In 1877, the building was extended, its frontage stretching the full 184 feet between 18th and 19th Streets. When the elevated railroad opened on Sixth Avenue in 1878, B. Altman was ready for a rush of customers. His store’s prosperity also benefitted the employees, who enjoyed shortened workweeks, subsidized lunch programs, and liberal medical benefits.

Altman Begins Collecting Art

The process of building the store’s name, clientele, and operations, as well as caring for his brother’s children, occupied nearly all of Benjamin’s time, but during the 1880s, he also began to satisfy a passion for collecting fine art. His first love was Chinese porcelains and ceramics that he began collecting in 1882, with a pair of Oriental vases costing only $35. This modest purchase led to meeting Henry J. Duveen, an art dealer of considerable stature.

It was a late Saturday evening when Benjamin arrived for his first viewing of Duveen’s gallery in New York, and he was almost too late to be served. The art dealer was preparing to go home, so Benjamin said, “I see that you are leaving and don’t want to bother you.” But, as luck would have it, the gallery owner was happy to oblige a prospective client. The two then toured the gallery and talked for nearly an hour before getting down to business. A cautious buyer, Benjamin waited for the dealer’s guarantee to refund the exact price of any item purchased, and he also explained, “I am a very busy man and can only come on Saturday nights after the close of my business.” Once the dealer agreed to accommodate the merchant’s unusual schedule, late Saturday meetings became a weekly ritual. The relationship of the two men lasted more than three decades, as Benjamin’s success provided the wealth to bring him into the ranks of America’s most prestigious art collectors.

Duveen became the most important agent in amassing the Altman collection, but it was Benjamin himself who decided what to buy. He cultivated expertise in art that interested him, and when not working at the store, he was constantly studying art and improving his home library at 24th Street and Madison Avenue. In 1888, Benjamin set off for what was probably the first vacation of his life, a grand tour of Europe, and throughout the trip, he showed taste and judgment in selecting art. His demands for precise histories of each piece and the depth of his knowledge frequently frustrated the hopes of dealers who sought an easy sale.

Bold Move to Fifth Avenue

Benjamin’s activities in the art world never distracted him from his love of business. His store thrived in the turbulent economy of the 1890s, and by the turn of the century, Benjamin had begun to purchase the real estate for a new, totally modern B. Altman store at 34th Street and Fifth Avenue.

His decision to move uptown was bold and perceptive. B. Altman & Co. had as much as 88,000 square feet for its business at Sixth Avenue, but that seemed less impressive after 1896, when a competitor opened across the street. It was Siegel-Cooper’s giant store, “A City in Itself.” The competitive situation of the neighborhood had intensified dramatically. More than a dozen department stores were now concentrated there, leaving no practical site in the immediate vicinity for a store of the size and comfort Benjamin sought.

The predominantly residential Fifth Avenue was untried territory for a department store, but Benjamin believed the venture would succeed and bought the land at a premium price. The risks paid off, and Altman’s became the leader of a new northward migration that would once again change the commercial geography of New York City.

The new store became the architectural symbol of Altman’s commercial prestige. With an eight-story design inspired by Florentine palaces of the Italian Renaissance, architect Goodhue Livingston of the Trowbridge & Livingston partnership satisfied Benjamin’s desire for a fashionable, dignified, and aesthetically elegant structure. Soft sandstone imported from France achieved a distinctive façade whose “softness and warmth in color” was welcomed in The Architectural Record as “inexpressibly refreshing after one’s eyes have been tired by the ghastly cream-colored brick so popular in New York.” The interior combined style, detail, and comfort: Doorways and columns stood in symmetry with a central rotunda; handsomely carved mahogany finishing graced the counters and showcases; and modern conveniences such as telephones, electric lighting, and elevators balanced the classical tradition of design with 20th-century expectations. The main floor alone had 60,000 square feet of retail space.

Newspaper advertisements reminiscent of engraved invitations announced the debut of a new B. Altman & Co. On opening day, Monday, Oct. 15, 1906, thousands of customers streamed through the store, many of them suburbanites drawn by the convenience of the new Altman’s to the commuter railroad terminals at Pennsylvania and Grand Central Stations. Customers of long standing were delighted to find that the new floor plans nearly duplicated the Sixth Avenue store’s layout, but in a vastly improved environment.

The next morning, The New York Times reported: “The store adds materially to the beauty of Fifth Avenue.” Benjamin, of course, would have settled for nothing less. He was as much committed to preserving the avenue’s high reputation as he was to keeping a first-class store. An active member of the Fifth Avenue Association, he had found space for Duveen’s gallery at 302 Fifth Ave. some years earlier. Benjamin himself was by then a resident of the avenue, taking a mansion on property owned by Columbia University at the northwest corner of 50th Street.

Art Collection Expands

Home was the center of Benjamin’s art interests. He employed three secretaries to help with his correspondence with connoisseurs and dealers throughout the world. They also updated the catalog of his art and library, for Benjamin was frequently weeding less-desirable items from the collections and replacing them with pieces of finer quality. But it was the masterworks themselves that transformed Benjamin’s mansion into a modern-day Aladdin’s cave.

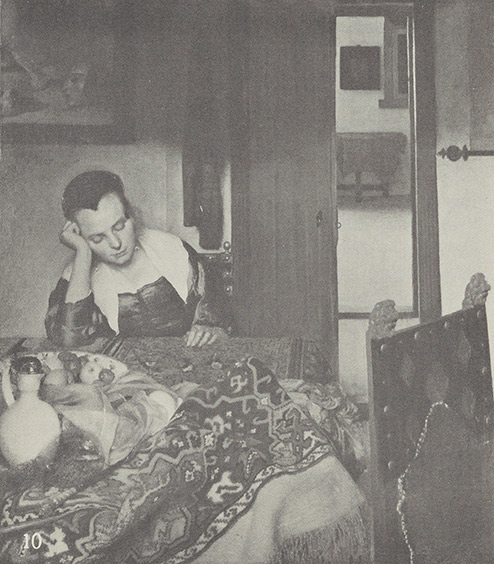

More than merely housing Benjamin’s art treasures, the galleries expressed an individuality, and a unique aesthetic consistency and exhibition style. Rare rugs were neither encased nor hung, for Benjamin preferred to lay them on the floor, where they complemented the antique furniture. Porcelains, enamels, and jade and crystal carvings, however, were protected in cases, mostly closed. And his paintings, hung high above the cabinets, were set “on a line that is a single line and not one above the other,” in defiance of prevailing custom.

Michael Friedsam, Benjamin Altman’s partner for many years before the new Fifth Avenue store opened, was 18 years younger than Benjamin, but the two men were much alike. Both were able merchants; both had exquisite taste. Both had the utmost consideration for employees; and both were art collectors. It was an ideal partnership. When one or another was away, the store was in good hands. However, sometimes the two men traveled together, viewing and collecting art. One such occasion was a trip to Europe in 1909, when Benjamin purchased three Rembrandts (bringing his collection to eight) and a Ruisdael from the Maurice Kahn estate.

When he returned from Europe aboard the Kaiser Wilhelm II in September 1909, Benjamin was met by a corps of eager reporters. In a rare interview, he revealed plans to loan some of his paintings to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art as part of a major exhibition of 149 Dutch paintings, shown in conjunction with a statewide celebration of Henry Hudson and Robert Fulton. “I left New York rather hurriedly, before the plans for the Hudson-Fulton Celebration had been shown to me, and I had no time to do my share,” Benjamin said.

Altman’s Philanthropy

This art loan to the Metropolitan foretold the eventual disposition of Benjamin Altman’s entire collection. Although the world did not yet know it, in June of 1909 he had bequeathed all of his art to the Metropolitan.

His bequest, however, did not end Benjamin’s collecting activities. Early in 1910, for example, his collection of Rembrandts increased to 11, and another two were added before his death in 1913. His assemblage of paintings by then also contained works by Botticelli, Holbein, Titian, Mantegna, Velasquez, and other masters. Some, like Mantegna’s “Holy Family,” commanded record-breaking prices when Benjamin bought them. After 30 years of careful collecting, Benjamin had gathered 50 paintings, 429 Chinese porcelains, and 438 other objects of art—tapestries, rugs, crystal, antique furniture, sculptures, jewelry, rugs, and more—valued then at $15 million.

Benjamin spent most of his last years at home, conducting a little business, but mostly looking after his art collections and arranging for the disposition of his property. He had suffered from kidney and heart trouble for a few years and returned from a brief vacation in September 1913 in poor health. It was only the day before his death that Benjamin took to his bed, where, at 4 p.m. on Oct. 7, 1913, he died at age 73. A niece, Lulu Fleishman Heymann, was with him.

In a long and unique career, Benjamin Altman accumulated a fortune, a world-famous art collection, and made the name B. Altman & Co. famous throughout New York. Yet, when he died, the newspapers did not have a single photograph of him on file. It was said that fewer than 100 people “even knew him by sight.” His reclusive behavior and rejection of publicity, however, made his legacy even more special, for he gave most of his wealth to public purposes.

He left substantial inheritances to his nieces and nephews. To the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he left a bequest that museum trustees deemed “the most splendid gift that a citizen has ever made to the people of the city of New York.” To the Altman Foundation, founded shortly before his death, he bequeathed all of his capital stock in B. Altman & Co.—valued at more than $20 million—for the support of public philanthropy as well as his store’s employees. Other gifts were bestowed upon the National Academy of Design, several New York hospitals, and the Educational Alliance.

Afterword

The B. Altman store was fortunate in having for its administration a succession of four talented and dedicated presidents. When he died, Benjamin Altman left his close friend and partner, Michael Friedsam, in charge. He served until 1931, when John S. Burke became president. He was followed in 1962 by his son John Burke Jr. Each of these men served as both president of the Altman Foundation and chief executive of the store.

In 1985, the Altman Foundation complied with the new requirements of the Tax Reform Act of 1969, which required the divestiture by a private foundation of control of a corporation like Altman’s and sold its stock ownership of the store to an outside group. John Burke Jr. continued as president of the Altman Foundation. One of its early beneficences was the establishment of the B. Altman Fund in The New York Community Trust.