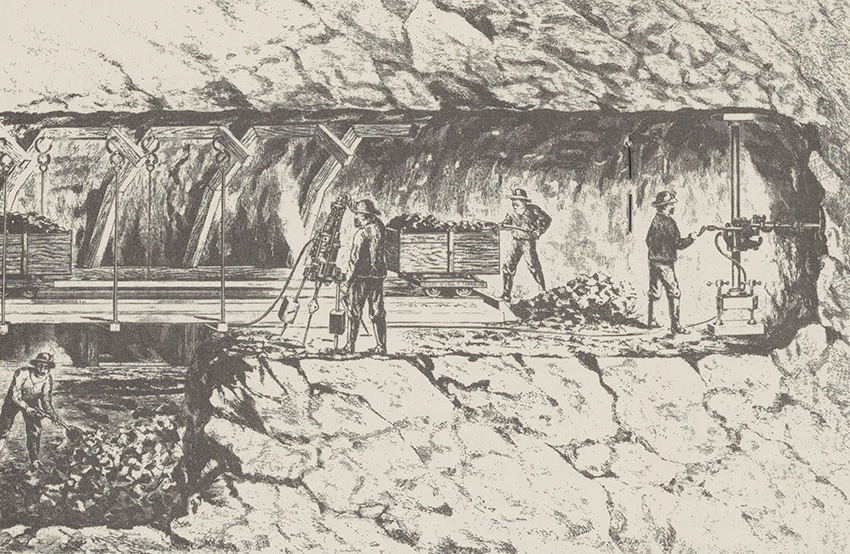

Inventor’s drills excavated tunnels and aqueducts around the world.

Addison C. Rand (1841-1900)

George A. Howells (1864-1937)

It was a summer day in 1886. The tall, dark-eyed young man was plainly nervous. He strode from one side of the small, sparsely furnished waiting room to the other. He returned, sat for a time on the edge of the single straight-backed chair, then paced some more—all the while keeping his eye on the door with the simple black lettering: Addison C. Rand, President.

George Howells was applying for a position with the Rand Drill Company. He had heard a great deal about the firm that had pioneered the development of rock drills, and he knew these tools had completely revolutionized the techniques of digging tunnels, boring conduits for aqueducts, and excavating mines. He believed the company could use his newly completed training as a mechanical engineer. He had heard, too, about the genius—and, some said, the stubbornness of the company’s president. And he was certain Addison Rand was the man he wanted to work for.

At last, the door opened, and Addison Rand invited George into his office. Addison looked impressive, his full, dark beard flecked with gray. His voice and manner were gruff and direct, but his eyes seemed kind. As the two men talked, George’s uneasiness slowly began to disappear. They spent a long time together that day, discussing not only the work George could do for Rand Drill, but also exploring his views on politics and many other areas. Addison Rand had a reputation for selecting employees as carefully as if he were bringing a member into his own family. He was not given to hasty judgments, and he was seldom wrong in his decisions about people. It was often said that his astuteness in choosing associates was one of the chief factors in his success. When, at the close of the interview, Addison Rand offered a position and George Howells accepted, it was the beginning of a mutually rewarding relationship on personal as well as professional levels.

Addison Crittenden Rand was born in Westfield, Massachusetts, on September 17, 1841. He was the son of Lucy Whipple Rand and Jasper Raymond Rand, the descendant of an early settler who had arrived in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1635. Addison and his two older brothers, Alfred and Jasper Jr., spent their early years in Westfield, where their father was a successful manufacturer of hoop skirts and buggy whips, and they went to school there. Alfred, the eldest, showed early signs of a talent for salesmanship. Jasper had a flair for organization. Addison’s bent was mechanical. While the three boys were growing up, they often talked of the businesses they would operate someday. But the Civil War intervened. Addison joined his local regiment, which was sent south to fight. After the picturesque port city of New Bern, North Carolina, was captured by Union forces in March 1862, Addison was appointed acting postmaster there.

When the war was over, the Rand brothers returned home and began to put their boyhood dreams into practice. In 1865, Jasper and Addison, who was now 24, took over their father’s manufacturing business. For a half-dozen years, they traveled between the plant in Westfield, where they also lived, and their company offices in New York City. Then Addison and Jasper decided to join their older brother in New York.

Alfred was a dealer in black powder who had succeeded in the manufacture of explosives and helped found the Laflin & Rand Powder Company. He was looking for a way to expand the market for his explosives, and he called on his brothers for help. Addison became convinced that a mechanical drill, using blasting powder, would greatly increase the demand for his brother’s product. He already had heard that such a drill had been invented, and, after studying numerous proposed designs for a rock-drilling machine, he and his brothers decided to form a company to develop and distribute them.

The Rand Drill Company was formed in 1871, with Addison as president and chief idea man, and Jasper, whose talent was finance and administration, as treasurer. The genius of three inventors—Joseph A. Githens, George Nutting, and Frederick A. Halsey—provided the initial impetus for the pioneering company, while Addison devoted his efforts to developing the inventions and bringing them to a state of practicability. At about the same time, Addison began to see the possibilities of adapting compressed air to new uses, and he spent much of his time perfecting air-compressing machinery.

In those days, all underground excavation was accomplished entirely by hand with pick and shovel, hammer and chisel, through even the hardest rock. The use of explosive-powered mechanical rock drills and compressed-air machinery was an entirely new concept, and, at that time, the future of such equipment was uncertain. But as the Rands persevered, they saw their ideas and machinery slowly gain acceptance. Eventually, rock drills and air compressors became standard equipment in constructing tunnels and aqueducts and in mining and quarrying operations throughout the world.

In 1885, the Rands’ equipment was used to clear the rocks from New York’s Hell Gate, a narrow channel of the East River at the north end of Manhattan that had long been dangerous to ships because of rocks and strong tidal currents. The aqueducts supplying drinking water to New York City and Washington, D.C., were built with the aid of Rand equipment. Railroad tunnels in Haverstraw and West Point, New York, and Weehawken, New Jersey, as well as many other tunnels, were cut with Rand drills.

Addison earned a reputation for being a stubborn, stern-principled businessman as well as a remarkably creative engineer. He established a plant at Tarrytown, New York, several miles north of New York City on the Hudson River, to take advantage of the cheap river transportation. He soon learned, however, that in winter, when the river often froze and navigation ceased, shipments had to be made by rail and the local railroad took advantage of the situation to raise its rate exorbitantly. Rand considered such increases extortion, and rather than submit to the demands, he hauled his goods across country to a second, independent railroad that did not resort to such practices.

When a strike was called by workers in the Tarrytown plant in 1886, it came as a great shock and disappointment to Addison Rand. Although he was not a demonstrative man, he felt he treated his employees with fairness and generosity, always going out of his way to express his appreciation for their services in practical ways. One of his workers, for example, was a man of limited education, but, Addison perceived, fine potential. He encouraged the man to enroll in a correspondence course and allowed him time off from work to complete his studies.

As a man who took such a close personal interest in his employees, Addison was dumbfounded when they refused to work unless their demands were met. He felt betrayed and was in no mood to yield easily to demands he believed to be unjust. His broad streak of stubbornness emerged clearly as he fought the strike. The plant was shut down for nearly a year before an agreement was finally reached.

Addison’s talents as an engineer and businessman were in considerable demand, and he was actively associated with a number of companies and organizations. He was president of the Pneumatic Engineering Company, and he held the offices of secretary and treasurer of the Rendrock Powder Company and the Laflin & Rand Powder Company, both founded by his brother Alfred. Addison served as treasurer and director of the Davis Calyx Drill Company and was a bank director.

He also participated in several professional organizations. Addison was one of the incorporators of the Engineers’ Club in New York. In 1888, he was elected its first treasurer and worked hard to make the fledgling group a success. He also was a member of the professional societies of mining engineers, civil engineers, and mechanical engineers. Proud of his old New England heritage, Addison also belonged to the Colonial Club of New York and was a director of the New England Society.

As a lifelong bachelor, Addison’s chief interest was always his work. However, he was very fond of horses, and his principal forms of recreation were riding and driving through the countryside surrounding his home in Montclair, New Jersey. He was 58 when he died March 9, 1900, after a brief illness.

Five years later, the Rand Drill Company was merged with another manufacturer of rock drills, a company founded by Simon Ingersoll. As a farm boy in Connecticut, Ingersoll had demonstrated an irrepressible urge to invent things. In 1871—coincidentally the year the Rand Drill Company was established—Ingersoll patented the first rock drill that could be used to drill vertical holes. Mounted on a tripod with weighted legs, rather than on a carriage as drills that could cut only horizontally were at the time, Ingersoll’s invention opened a vast new market. That same year, Henry Clark Sergeant, an expert mechanic, improved Ingersoll’s drill as a practical tool and founded the Ingersoll Rock Drill Company. Later, Sergeant left the firm to organize his own company. He then came back to merge his firm with Ingersoll’s to form the Ingersoll-Sergeant Drill Company. In 1905, that company merged with the Rand Drill Company to form the Ingersoll-Rand Company.

One of the firm’s most experienced and valuable employees was George A. Howells, the young mechanical engineer Addison had hired 19 years earlier. His presence in the firm proved once again the soundness of Addison’s judgment.

Howells was born in New York in 1864, the son of George and Mary Glasgow Howells. Soon after George began working at Rand Drill, he married Marian Hoornbeck, the daughter of Louis and Margaret Schoonmaker Hoornbeck. Like most of the men Addison hired, George had quickly proved his mettle and had earned ever-increasing responsibility in the company. He was a quiet, matter-of-fact man, little given to conversation but considered an excellent analyzer of complex problems. By the time of his mentor’s death, George, then 36, was firmly entrenched in the organization. He took his place with quiet competence in the newly formed company, and, until he died, continued to make substantial contributions to the work of Ingersoll-Rand.

George and Marian Howells had no children, but they were deeply involved in education and community service, especially in Kingston, New York, where they lived in their later years. Marian was vivacious and more outgoing than her husband, but both were generous supporters of charitable organizations in their town and county.

For many years, they spent summer holidays at the Mohonk Mountain House, a quiet, genteel retreat in the Catskills where automobiles were left outside the gates and guests toured the spacious grounds by horse and carriage. At this resort, they met Martha Berry, who in 1902 had opened a log-cabin school for five underprivileged mountain children in the Southern Appalachians of Georgia. From this simple beginning, Martha developed the Berry Schools, offering liberal arts and vocational training to over a thousand students who worked out their tuition by making bricks from which the buildings were made, and taking care of their own cooking and housekeeping. It was the kind of situation that appealed to a man who venerated hard, honest work, and George and Marian were substantial supporters of the Berry Schools during their lifetimes. The Berry Schools evolved into Berry College, which enrolls about 2,200 students and is ranked as one of the best regional colleges in the South by U.S. News & World Report.

When George A. Howells died in Kingston on June 7, 1937, at age 73, he was the oldest employee of the Ingersoll-Rand Co. He had never forgotten his early years of association and friendship with Addison Rand, the man who had given him his start. In grateful memory of the man whose professional help and personal friendship had meant so much, George A. Howells provided in his will for the establishment of the Addison C. Rand Fund, so the help Addison Rand had extended to so many during his lifetime might be carried on in future generations.