A New York City publishing giant, Delacorte established funds for the arts and journalism.

George T. Delacorte (1893-1991)

George T. Delacorte, the founder of the Dell Publishing empire, was a quintessential New York City philanthropist. In a series of imaginative projects, often motivated by his fondness for Central Park and children, he literally put his name of some of the City’s best-known park features. Notable among them is the Alice-in-Wonderland statue just north of the Conservatory Pond, given in memory of his first wife, Margarita, and the Delacorte Clock, the carousel at the Children’s Zoo whose resident statues of a bear, a concertina-wielding elephant, a horn-playing kangaroo, and other animal figures perform every half-hour to the sound of a glockenspiel.

A benefactor with a gift for dramatic and whimsical gestures, George was once dubbed by the New York Times as “a kind of slender Santa Claus.” Other papers saw him as a “delightfully eccentric philanthropist.” Simply put, his generosity gave him joy. Of the Alice-in-Wonderland statue he once said: “It just seemed a nice thing to have in the park. On Sunday mornings I watch the kids climbing over it, under it. It’s a regular parade.” His philanthropic vision was aptly summed up by the name of the charitable foundation he created in 1964, Make New York Beautiful Inc., formed to “promote interest and aid in the donation of permanent improvements to the City of New York for its cultural advancement and beautification.”

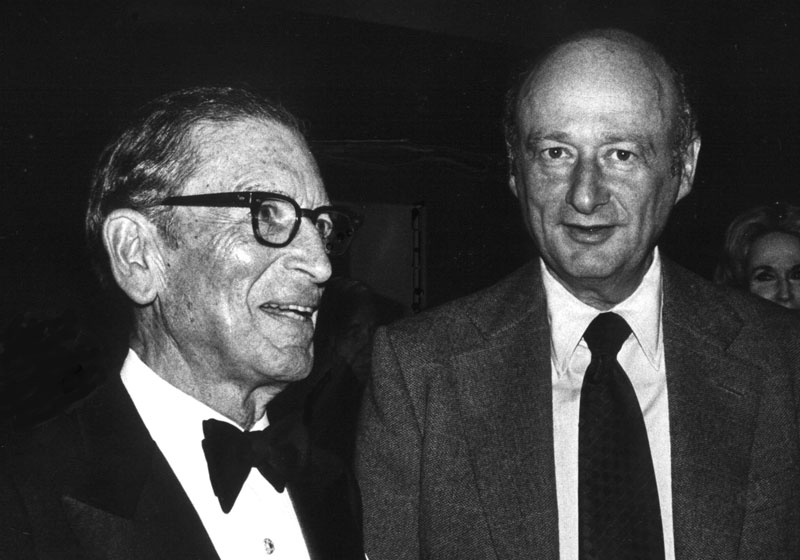

During his travels abroad, George became enamored of the fountains in European cities and believed that New York should have them too, leading to the installation of fountains at Columbus Circle, Bowling Green, and City Hall. (The City Hall fountain no longer exists.) He took offense at the once-fenced-in, littered medians on Park Avenue and offered Mayor John Lindsay to landscape them with flowers and trees. In appreciation of George’s generosity, Mayor Edward Koch proclaimed: “George T. Delacorte is to the City of New York what Lorenzo de Medici was to the City of Florence.”

On a 1969 trip to Geneva, George had another idea: New York should have a geyser equal to the Jet d’Eau in Lake Geneva—and what better place for it, he concluded, than the southern tip of then-garbage strewn Roosevelt Island opposite the United Nations? His illuminated geyser, at 400 feet, was to be the highest fountain in the world. Critics guffawed. In response, George replied with characteristic candor: “What good is it? What good is the Eiffel Tower? Not everything has to have a practical function.” But the $350,000 installation became an expensive headache. Although the fountain was plagued by mechanical difficulties, George covered all the maintenance expenses. Despite its problems, the geyser was his personal favorite among his many contributions to the City.

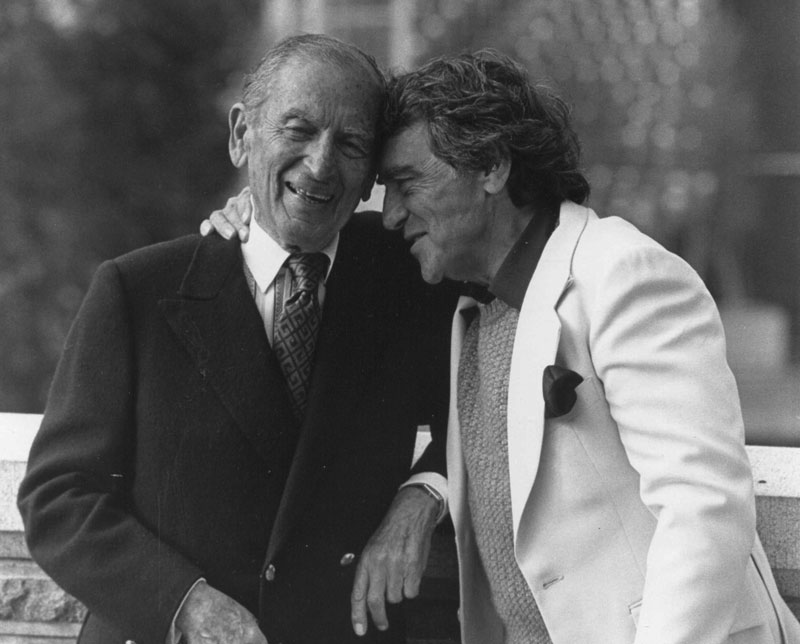

In 1961, George donated the 2,500-seat Delacorte Amphitheater for his friend Joe Papp, director of the world-famous New York Shakespeare Festival, which puts on free summer productions of the Bard’s plays in Central Park. In front of the amphitheater, George also donated statues by sculptor Milton Hebald of Romeo and Juliet and characters from “The Tempest.” A mobile Delacorte Theater made it possible to take Shakespeare’s plays to other parks around the City.

George Thomas Delacorte, Jr. was born in Brooklyn on June 20, 1893. He attended Boys High School and went to Harvard before transferring to Columbia, where he graduated in 1913. By that time, he was married and brought his baby son, Albert, to the ceremony. He was determined not to follow in the footsteps of his lawyer father and went to work for a small publishing company as advertising director for the magazine Snappy Stories.

After a disagreement with management, he left the job with $10,000 in severance pay—and a determination to start up his own publishing venture. In 1921, he founded Dell Publishing Co., a name chosen by his wife, Margarita. Dell began operation in a one-room office on West 23rd Street with George and a staff of two. Its first successful pulp fiction magazine was “I Confess” but soon, he was turning out dozens of magazines with penny-a-word stories: “Cupid’s Diary,” “Screen Stories,” and “Inside Detective.”

A satirical magazine, “Ballyhoo,” became a huge success. But there was a gimmick. “Ballyhoo” came wrapped in a new invention called cellophane and carried the slogan: “Read a fresh magazine.” The fourth issue sold more than two million copies.

To the delight of generations of children, his pulp magazines were soon joined by comic books—featuring Woody Woodpecker, Bugs Bunny, and Walt Disney characters such as Mickey Mouse and Pluto. Dell was soon selling 300 million comic books a year, with Walt Disney comics alone sometimes accounting for three million copies a month.

By the mid-1960’s Dell was one of the three leading American publishers of paperback books with such imprints as Delta Books, Laurel Books, and the Laurel Language series. It also owned the Dial Press and Mayflower Books Ltd. of London and had acquired Noble & Noble, a textbook publisher. In 1963 Dell had formed its hardback division, Delacorte Press, principally to assure a continuing supply of material for its paperback imprints. Among the writers lured to Delacorte by its generous contracts were best-selling authors James Jones, Kurt Vonnegut, and Irwin Shaw.

Long before women were given responsible positions in business, George hired Helen Meyer, still in her 20’s, who became a major force at Dell and in American publishing. “I’m a great believer in hiring women,” George once said. “If you have a capable man and your competitors know about it, they’ll start propositioning him. Women are more loyal. Women of course have their shortcomings. . . they leave to have babies.”

George Delacorte did not forget his alma mater, Columbia University. His gifts included the ornamental iron gates at Broadway and 116th Street; landscaping of College Walk and the great lawn at South Field; and new dormitories. With $750,000, he established the Delacorte Professorship in the Humanities, and in 1985, George, then in his 90’s, gave the university $2,250,000 to create the George T. Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism. To house the new center, the Journalism School’s roof needed to be raised and a new eighth floor constructed. To honor his contributions, Columbia named him the 1978 winner of the Alexander Hamilton Medal, the College Alumni Association’s highest tribute, and in 1982 he was awarded him an honorary doctorate of laws.

His other charitable interests included yearly gifts to Columbia Medical School and Old Masters paintings and maintenance funds to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

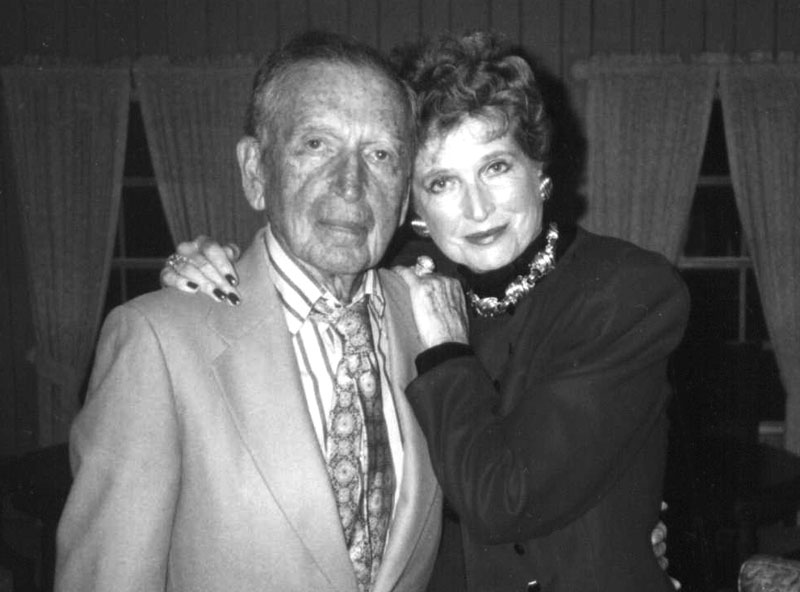

A widower, George remarried in 1959. His second wife, Valerie Pascal, was the widow of Gabriel Pascal, a movie producer. Valerie was a stage and film star in Hungary and the author of “The Disciple and his Devil,” an account of the relationship between her late husband and the playwright George Bernard Shaw.

In his later years, George remained vigorous—and mischievous. At age 93, he was asked, how does it feel to be so old? He playfully answered, “When you get to this age, first sex goes, then memory leaves you. But the memory of sex never leaves you!” George walked to work his entire life, and at 91 still played tennis. He was an ocean swimmer at age 95.

He died in his sleep at his Fifth Avenue home on May 4, 1991, a few weeks short of his 98th birthday. He had fulfilled his dream to give beauty and joy to his fellow man and to the City.